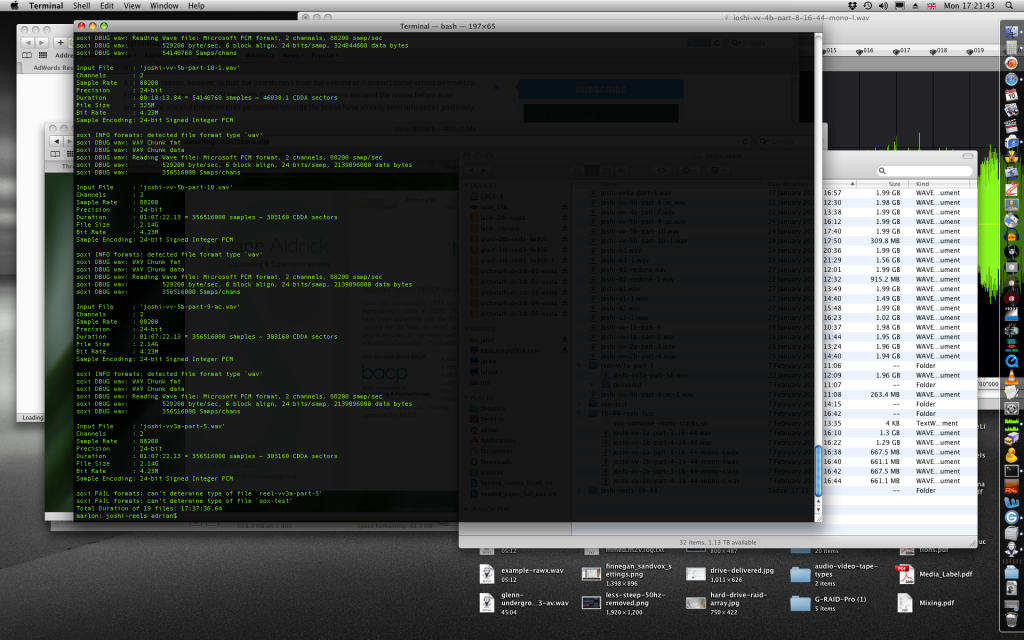

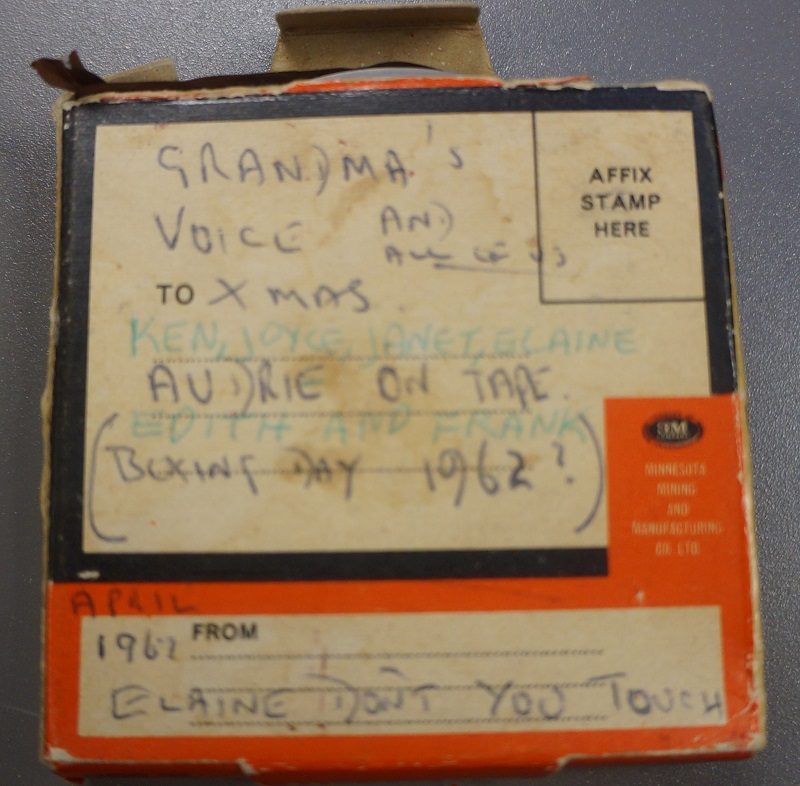

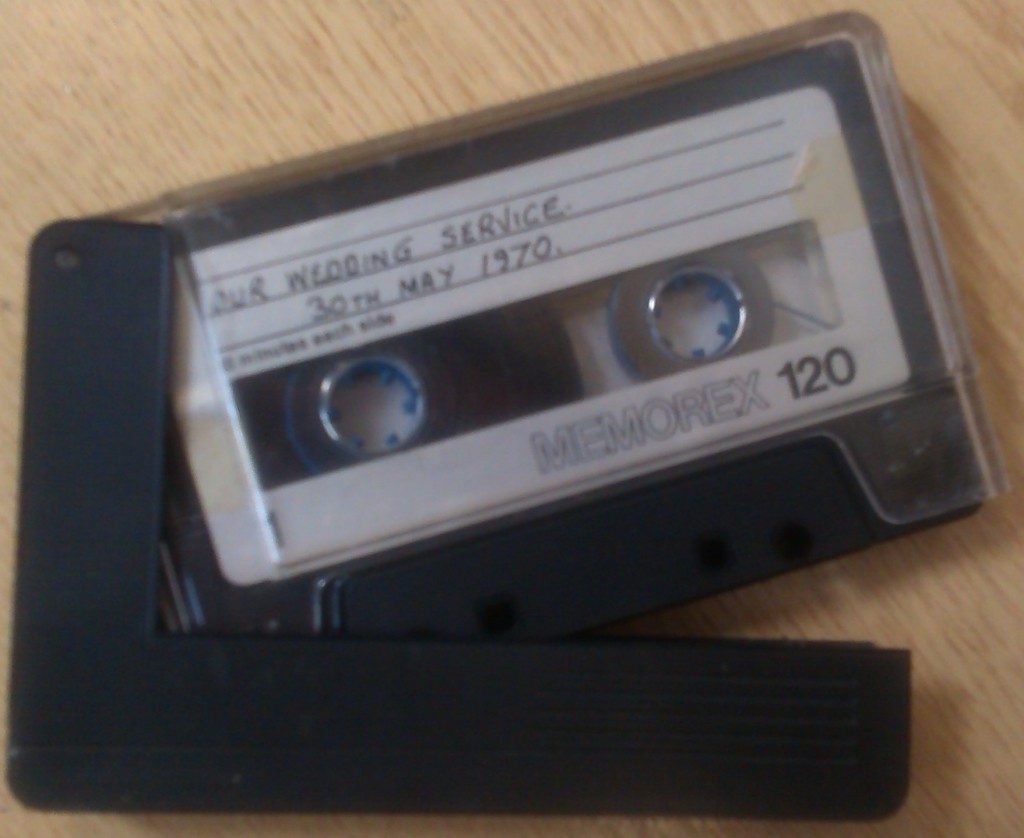

We understand that when organisations decide to digitise magnetic tape collections the whole process can take significant amounts of time. From initial condition appraisals, to selecting which items to digitise, many questions, as well as technical and cultural factors, have to be taken into account before a digital transfer can take place.

This is further complicated by that fact that money is not readily available for larger digitisation projects and specific funding has to be sought. Often an evidence base has to be collected to present to potential funders about the value and importance of a collection, and this involves working with organisations who have specific expertise in transferring tape-based collections to digital formats to gain vital advice and support.

We are very happy to work with organisations and institutions during this crucial period of collection assessment and bid development. We understand that even during the pre-application stage informed decisions need to be made about the conditions of tape, and realistic anticipations of what treatments may be required during a particular digitisation project. We are very willing to offer the support and advice that will hopefully contribute to the development of a successful bid.

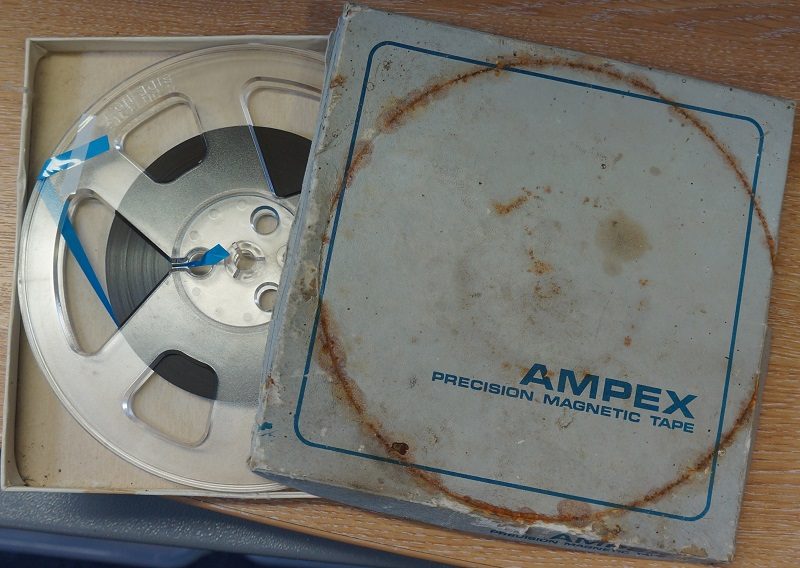

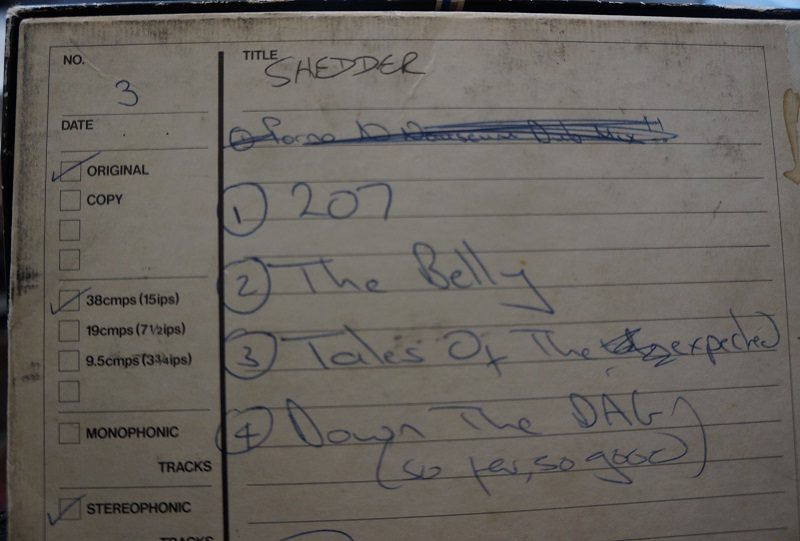

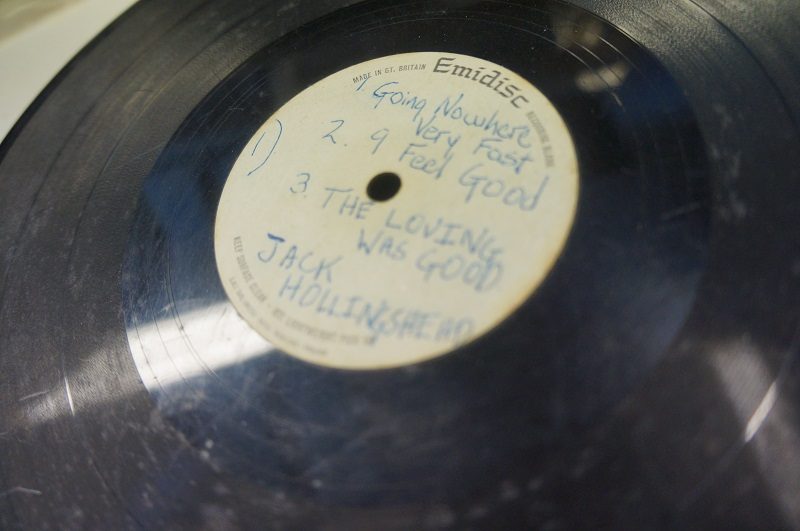

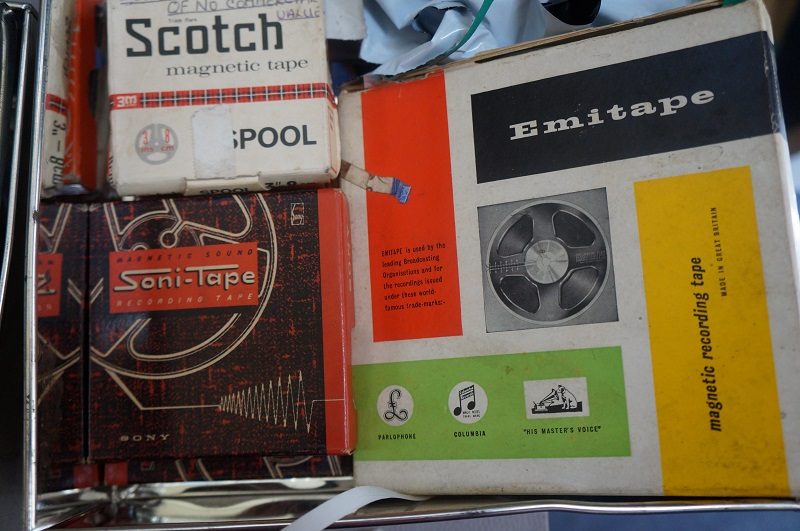

For example, we recently were contacted by Ken Turner who was involved in Action Space, an experimental, community theatre group established in 1968. Ken has a collection of nearly 40 EIAJ SONY video tapes that were made in the 1980s. Because of the nature of the tapes, which almost always require treatment before they can be played back, transferring the whole collection will be fairly expensive so funding will be necessary to make the project happen. We have offered to do a free assessment of the tapes and provide a ten minute sample of the transfer that can be used as part of an evidence base for a funding bid.

Potential Problems with EIAJ ½ Video Tapes

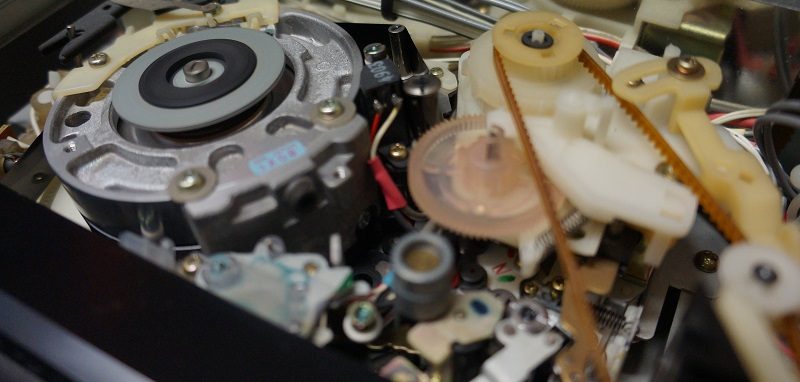

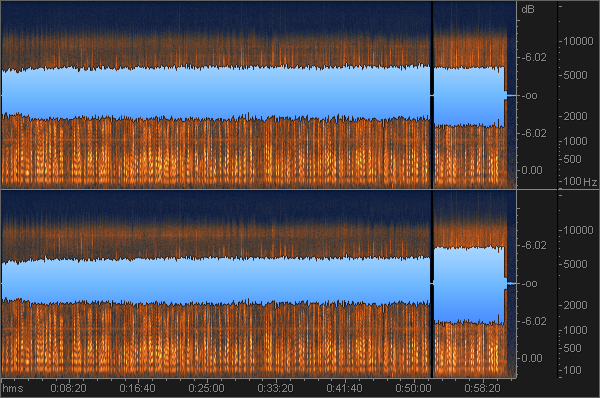

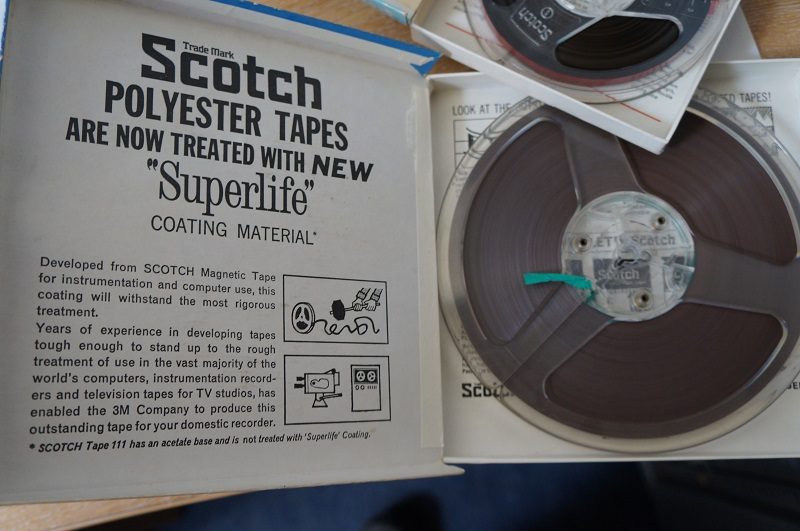

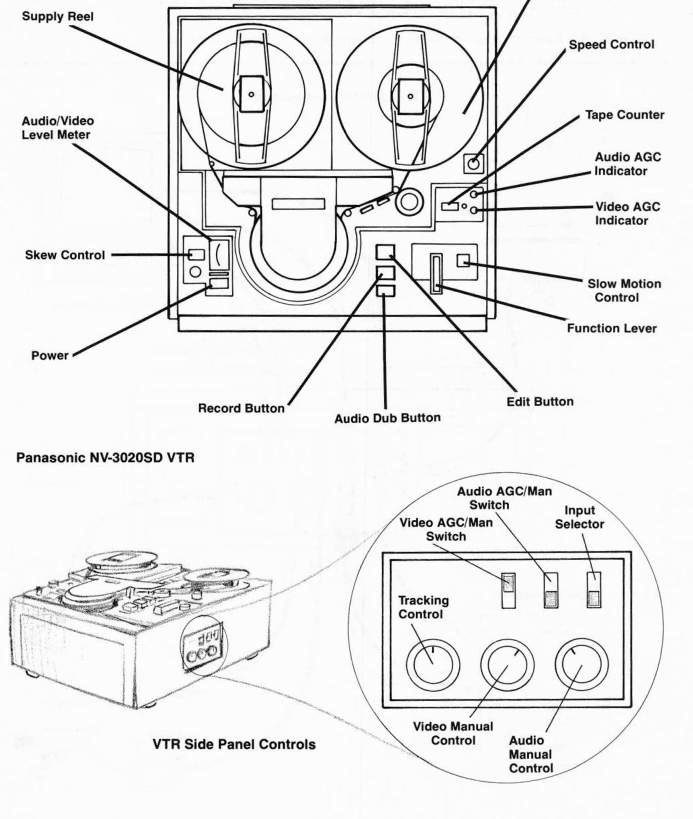

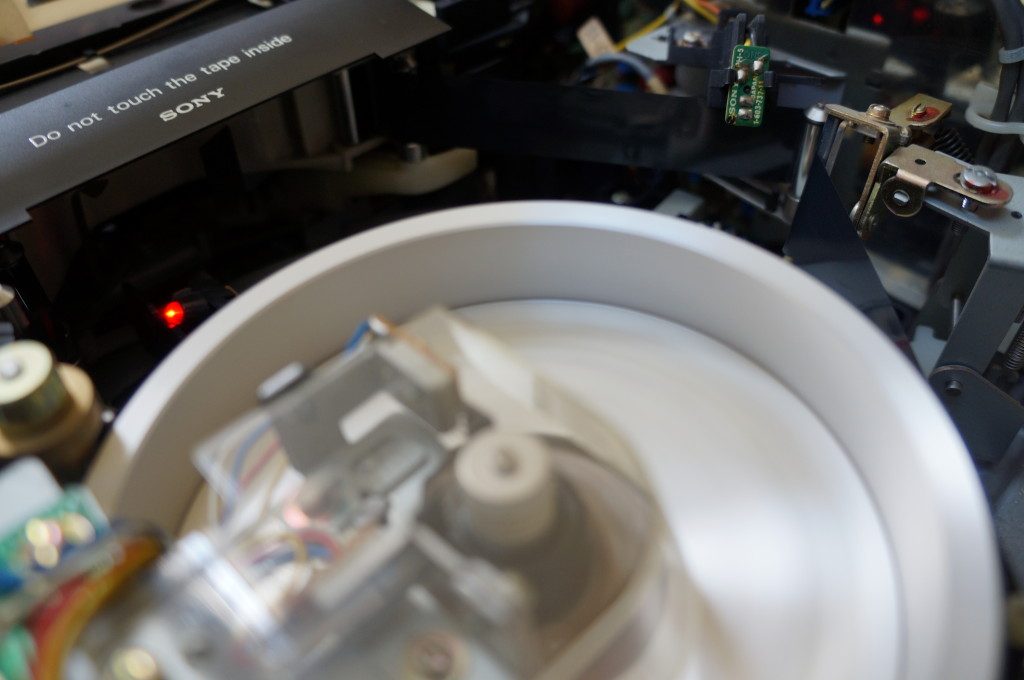

EIAJ tapes that have a polyethylene terephthalate ‘back coating’ or ‘substrate’ may also be affected by temperature or humidity changes in its storage environment. These may have caused the tape pack to expand or contract, therefore resulting in permanent distortion of the tape backing. Such problems are exacerbated by the helical scan method of recording which is common to video tape, which records parallel tracks that run diagonally across the tape from one edge to the other. If the angle that the recorded tracks make to the edge of the tape do not correspond with the scan angle of the head (which always remains fixed), mistracking and information loss can occur, which can lead to tracking errors. Correcting tracking errors is fairly easy as most machines have in-built tracking controls. Some of the earliest SONY CV ½ inch video tape machines didn’t have this function however, so this presents serious problems for the migration of these tapes if their back coating has suffered deformation.

The possibility of collaboration

We are excited about the possibility of working with the Action Space collection, mainly because we would love to opportunity to learn more about their work. Like many other theatre groups who were established in the late 1960s, Action Space wanted to challenge the elitism of art and make it accessible to everyone in the community. In their 1972 annual report, which is archived on the Unfinished Histories: Recording the History of Alternative Theatre website, they describe the purposes of the company as follows:

‘Its workings are necessarily experimental, devious, ambiguous, and always changing in order to find a new situation. In the short term the objectives are to continually question and demonstrate through the actions of all kinds new relationships between artists and public, teachers and taught, drop-outs and society, performers and audiences, and to question current attitudes of the possibility of creativity for everyone. For the longer term the aim is to place the artists in a non-elite set up, to keep “normal” under revision, to break barriers in communication and to recognise that education is a continuing process.’

Although Action Space disbanded in 1981, the project was relaunched in the same year as Action Space Mobile, who are still operating today. The centre of the Action Space Mobile’s philosophy is that they are an arts company ‘that has always worked with people, believing that contact and participation in the arts can change lives positively.’ There is also the London based ActionSpace, who work with artists with learning disabilities.

We hope that offering community heritage projects the possibility of collaboration will help them to benefit from our knowledge and experience. In turn we will have interesting things to watch and listen to, which is part of what makes working in the digitisation world fun and enjoyable.