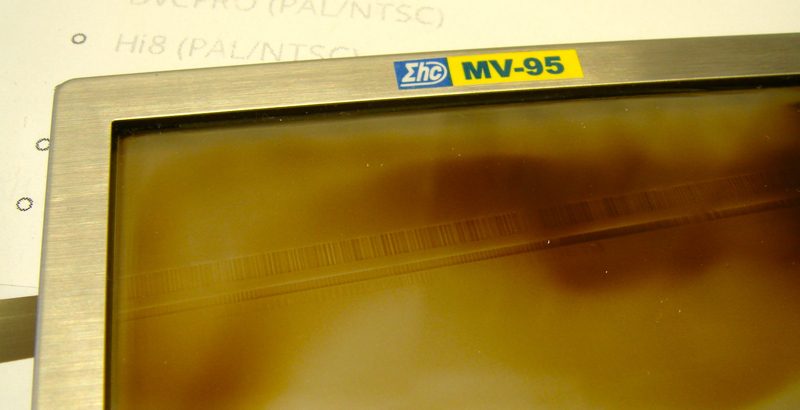

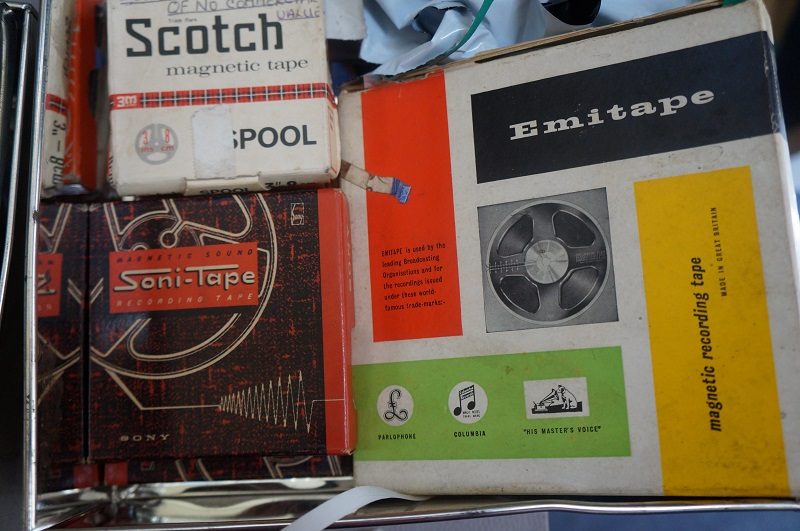

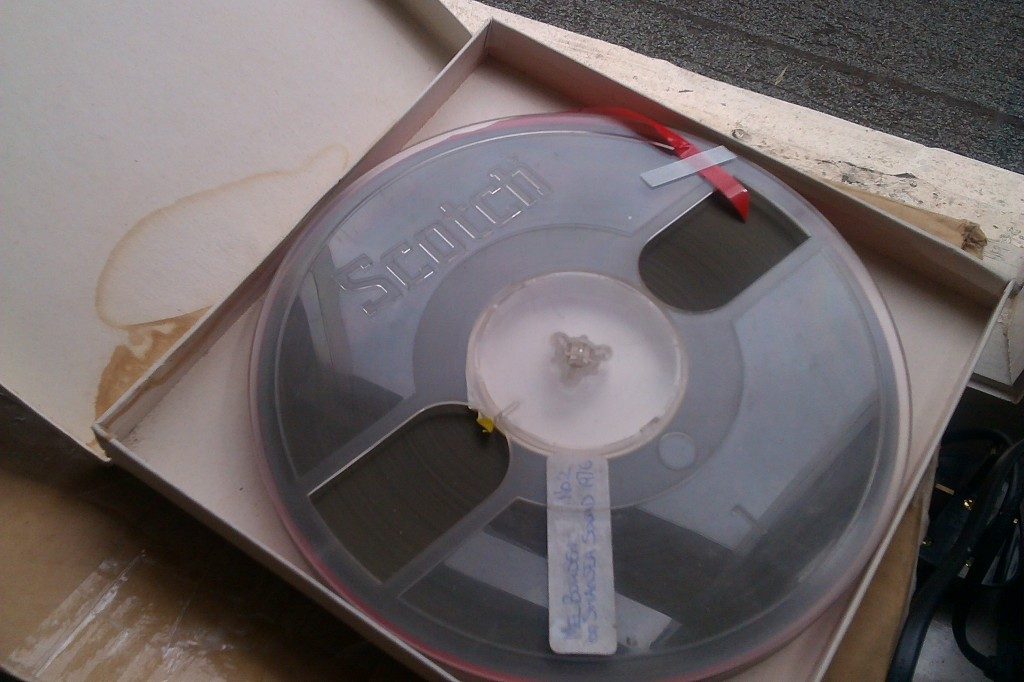

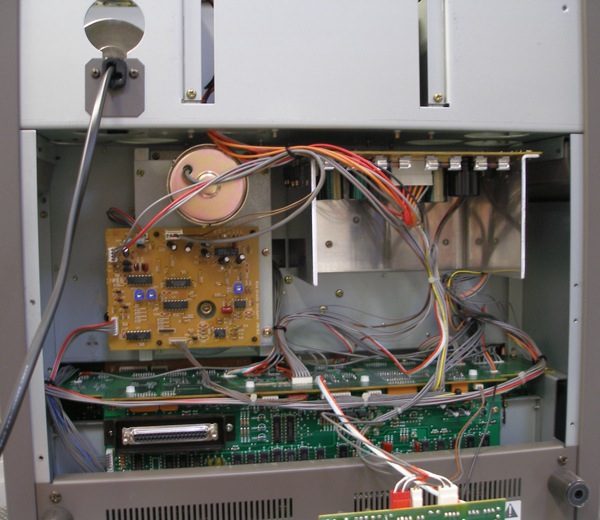

The effects of mould growth on both the integrity of the tape and the recorded sound or image can be significant.

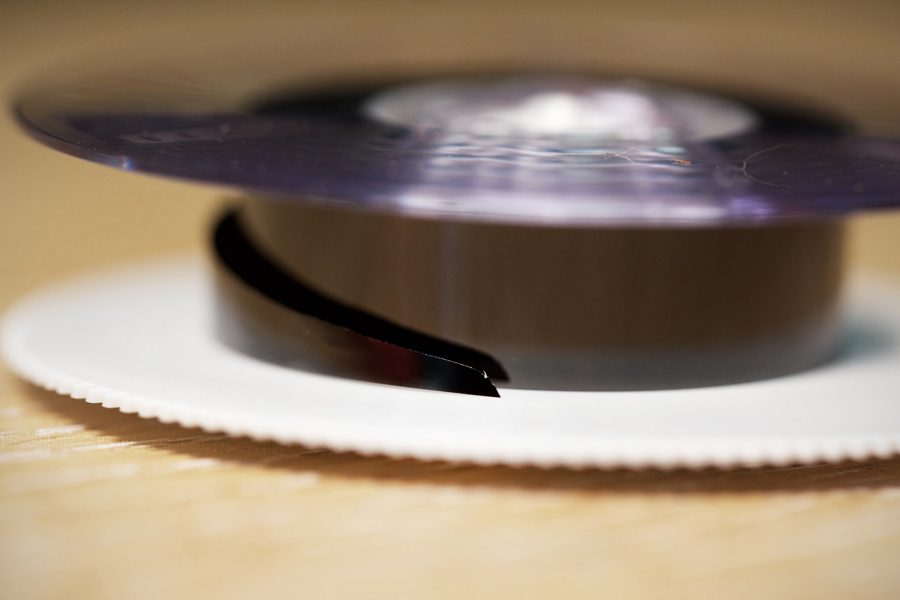

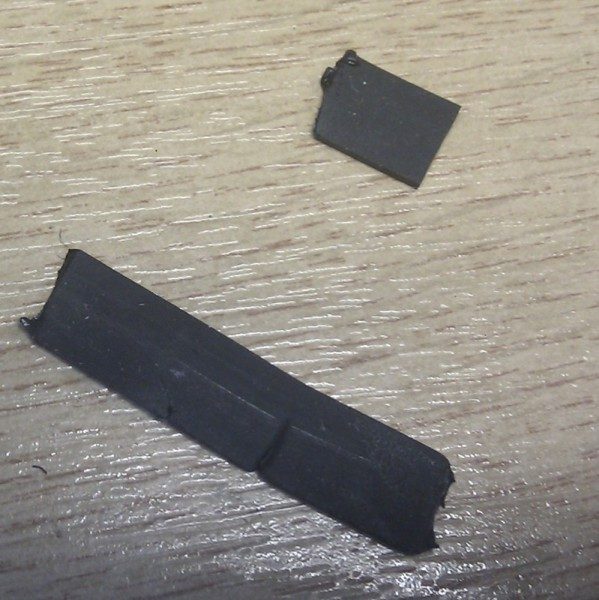

Mould growth often sticks the tape layers in a tightly packed reel together often at one edge. If an affected tape is wound or played this can rip the tape.

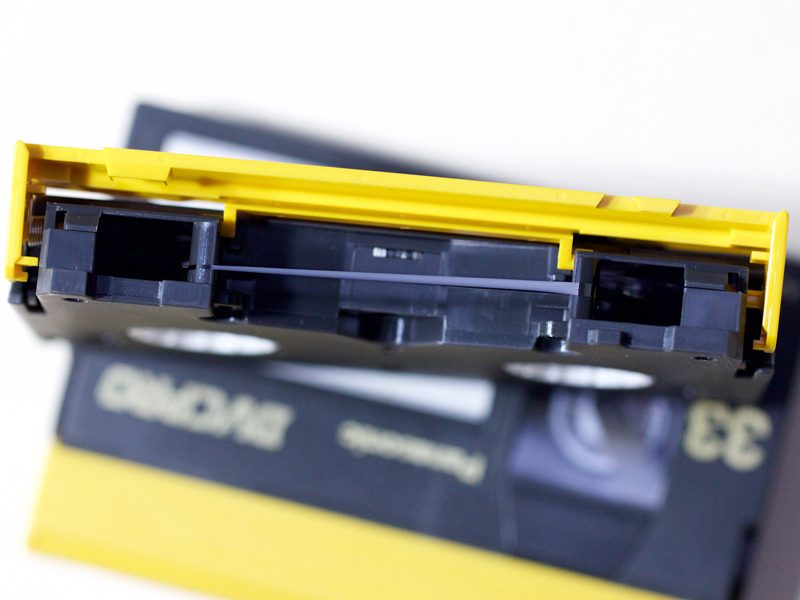

In the case of narrow and thin tapes like DAT, this can be catastrophic.

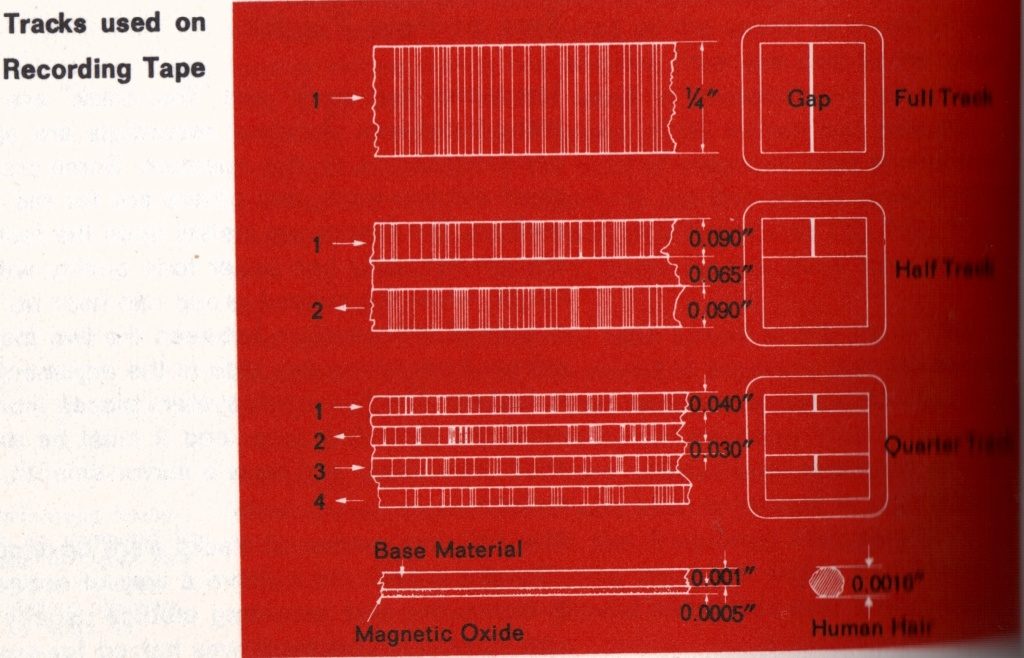

If the mould has damaged the record side of the tape then the magnetic tracks are usually damaged and signal loss will result. This will create audible and visual artefacts that cannot be resolved.

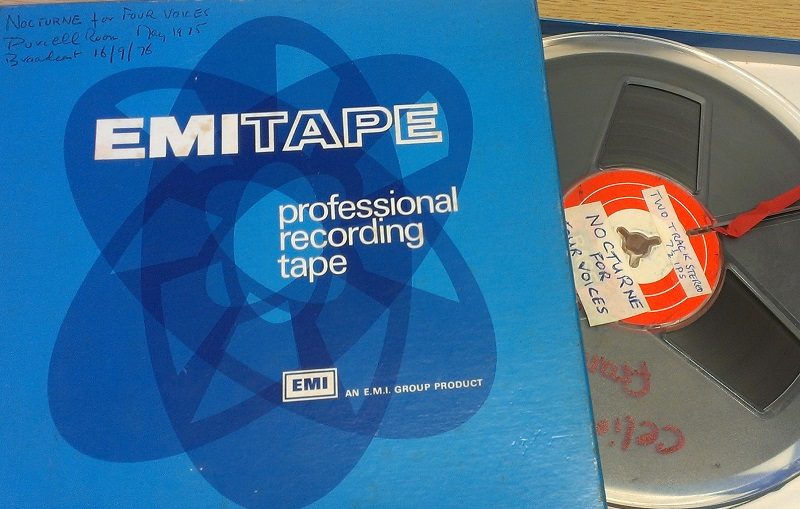

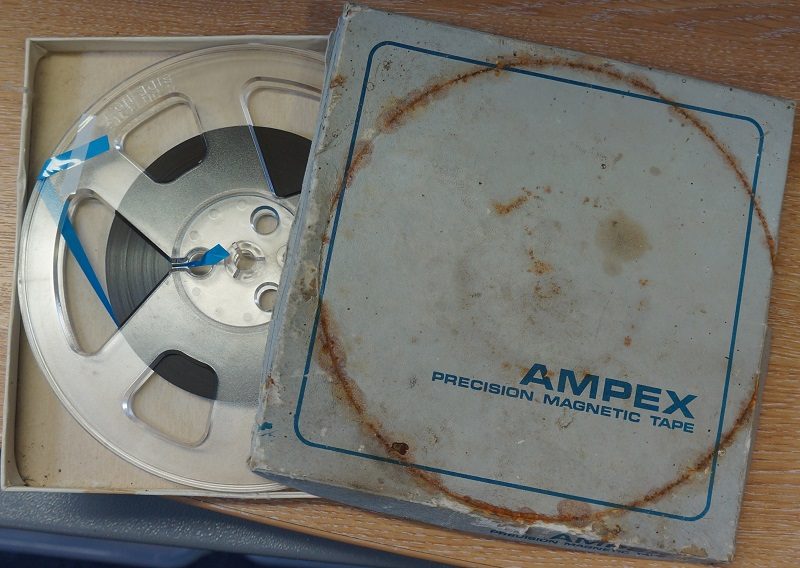

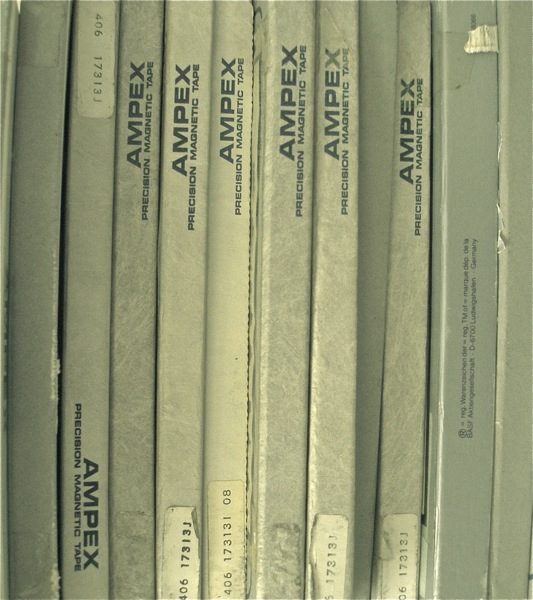

Mould develops on tapes that have been stored in less-than-optimum conditions. Institutional collections can exhibit mould growth if they have not been stored in a suitable temperature-controlled environment. For magnetic tape collections this is recommended at 15 +/- 3° C and 40% maximum relative humidity, although the British Library's Preservation Advisory Centre suggest 'the necessary conditions for [mould] germination are generally: temperatures of 10-35ºC with optima of 20ºC and above [and] relative humidities greater than 70%.'

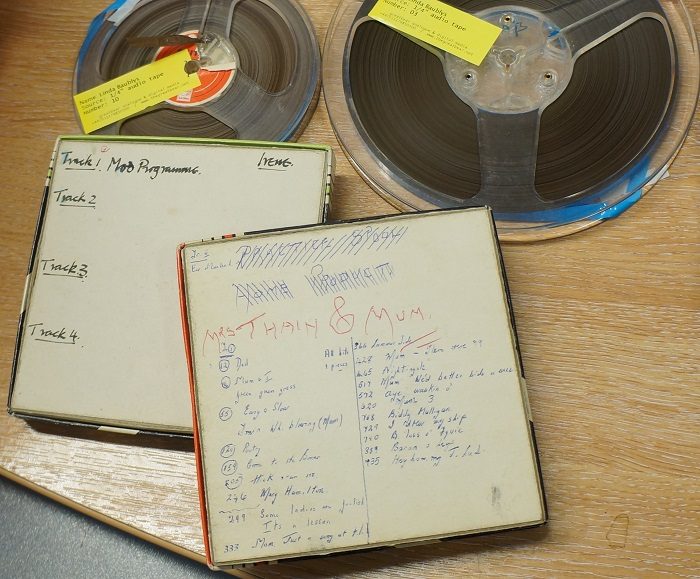

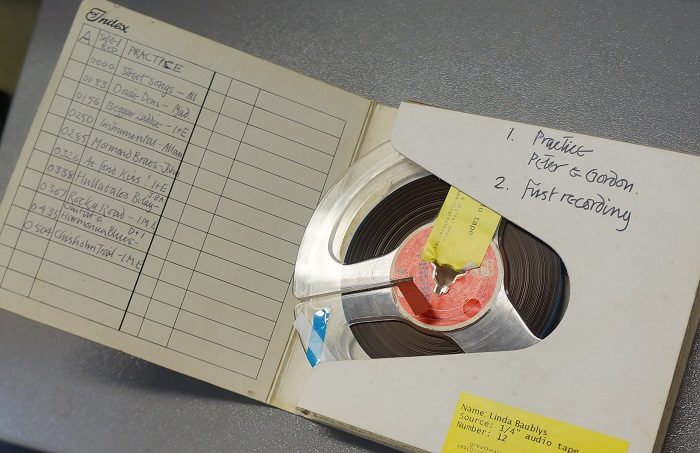

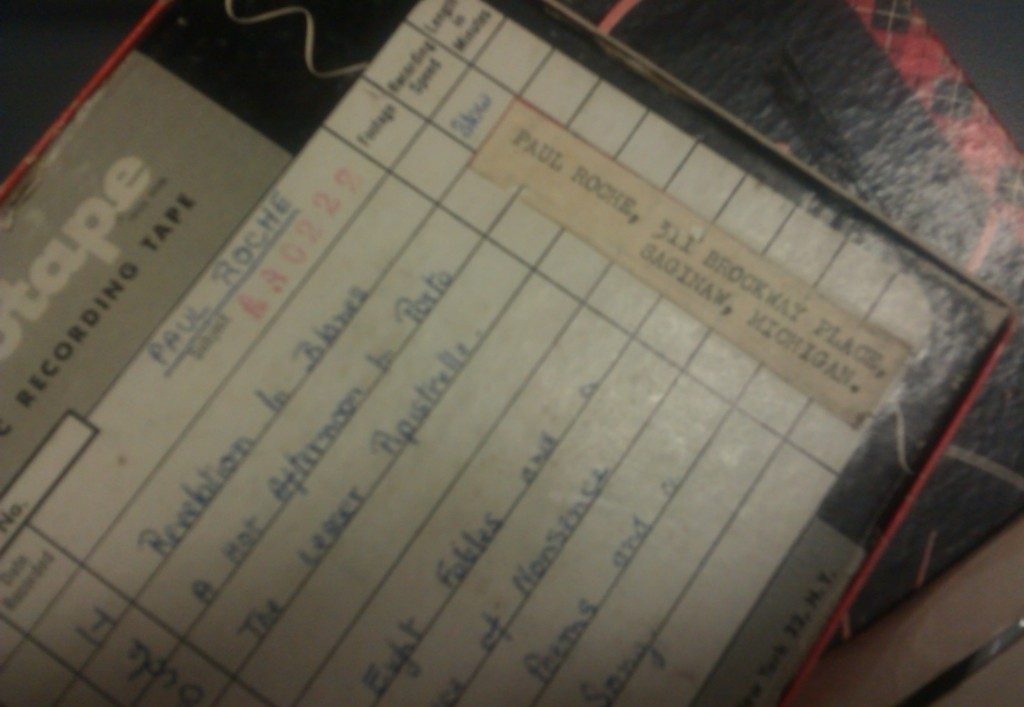

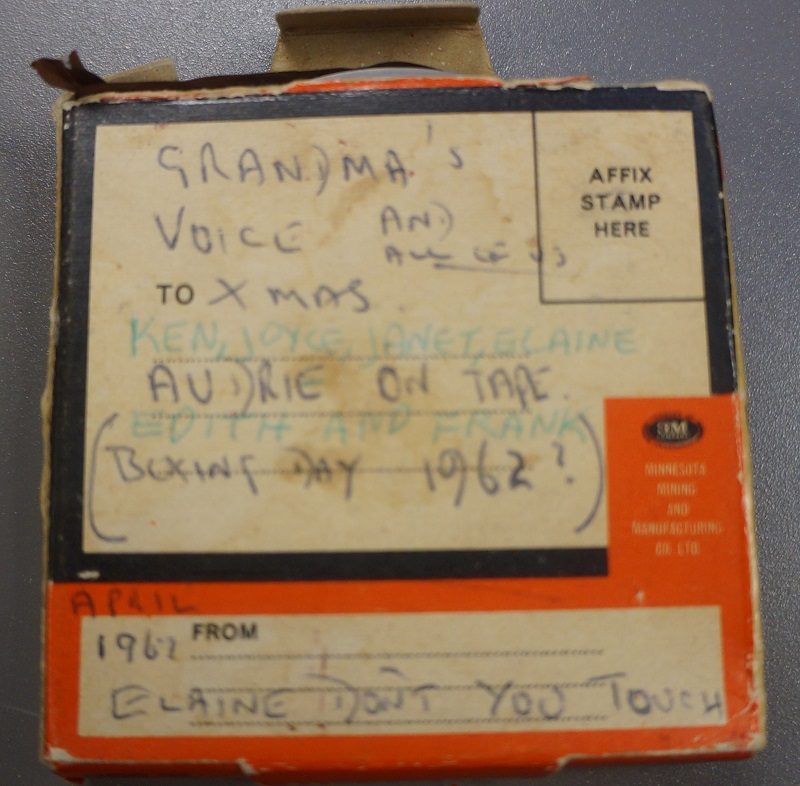

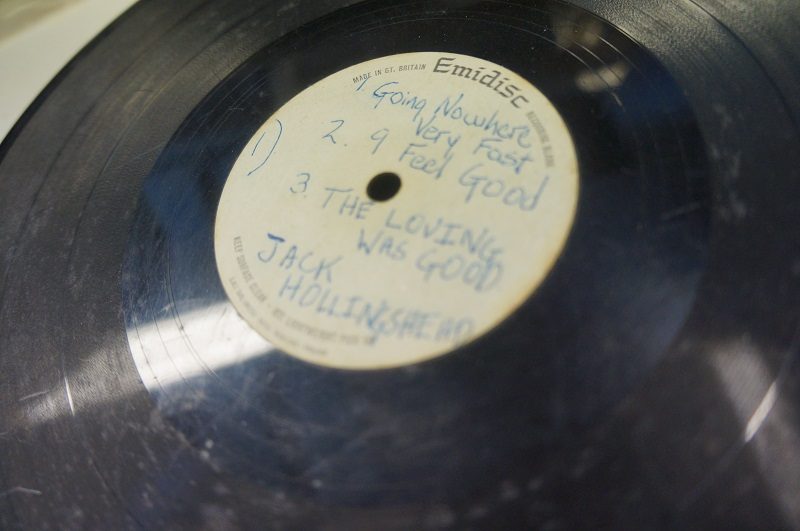

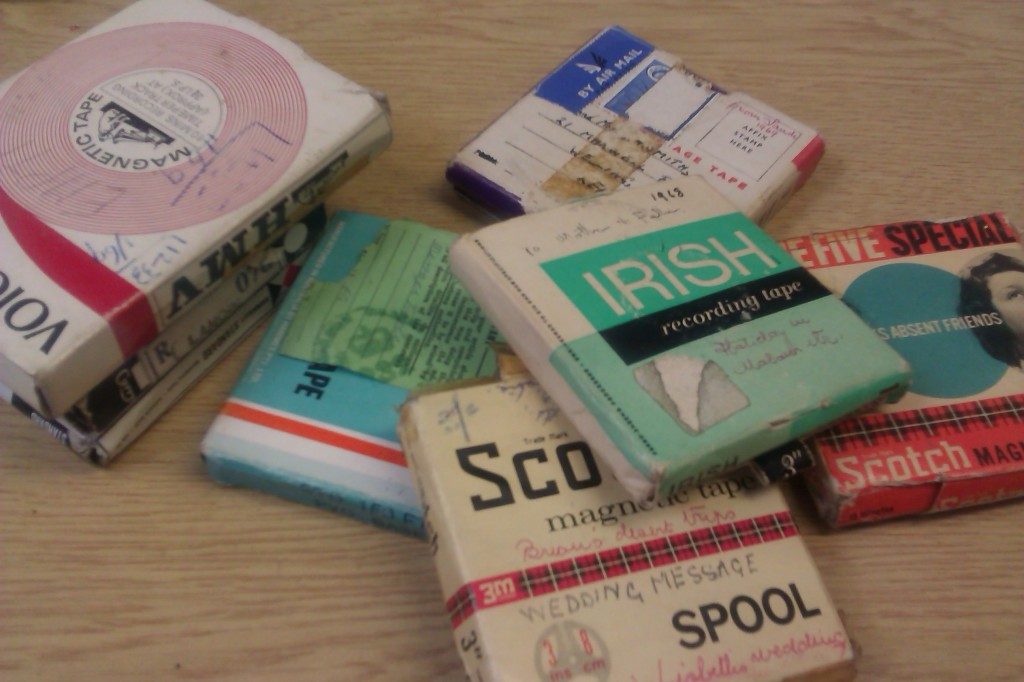

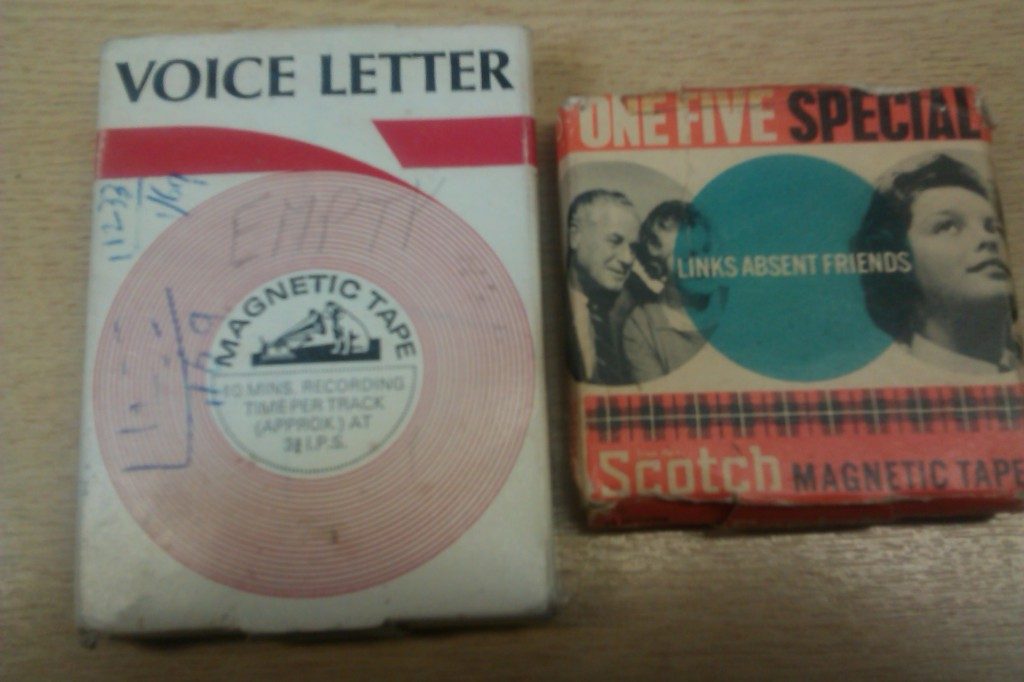

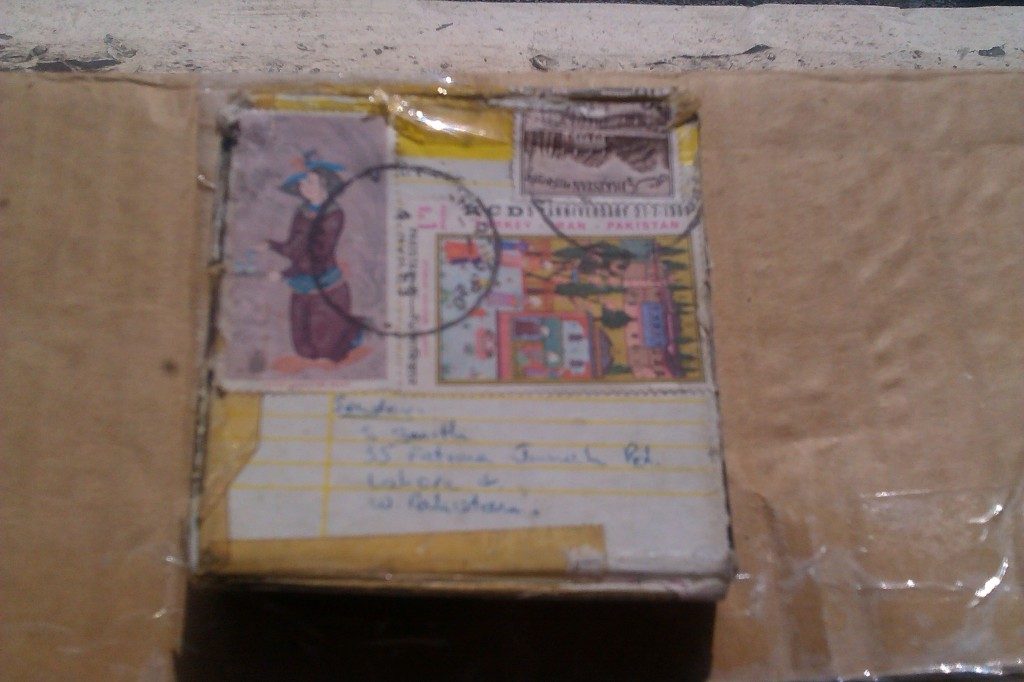

For domestic and personal collections the mouldy tapes we receive are often the ones that have been stored in the shed, loft or basement, so be sure to check the condition of anything you think may be at risk.

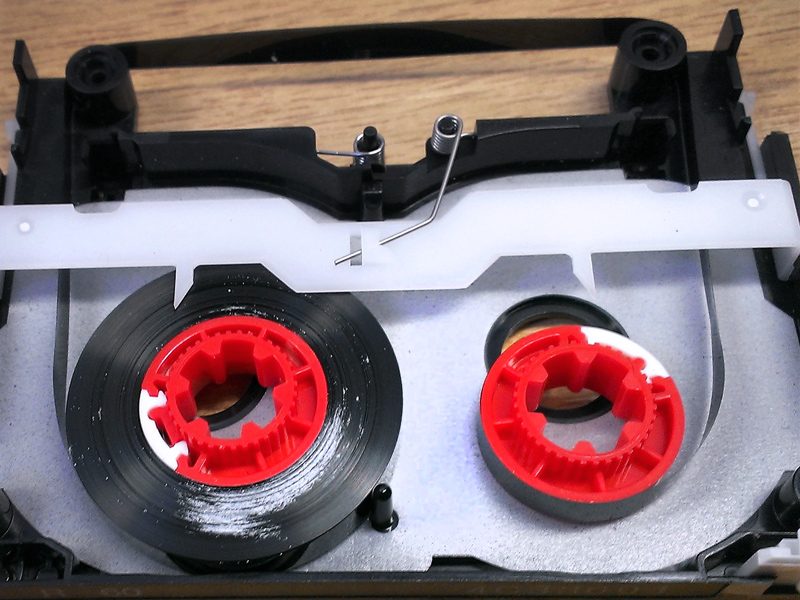

We do come across cases where mould is not easily visble to the naked eye without dismantling a cassette shell - so unless you can be sure your tape has been kept in optimum storage conditions for its entire 'life', it's better to err on the side of caution. Playing a mould-affected tape in a domestic machine can very easily damage the tape.

It is important to remember that a mouldy tape is a hazard not just for the individual tape. If not handled carefully it can potentially spread to other parts of your collection, so must be treated immediately.

What can we do to help?

We have a lot of experience treating tapes suffering from mould infestation and getting great results!

There are several stages to our treatment of your mouldy tape.

Firstly, if the mould is still active it has to be driven into dormancy. You will be able to tell if there is active mould on your tape because it will be moist, smudging slightly if it is touched. If the tape is in this condition there is a high risk it will infect other parts of your collection. We strongly advise you to quarantine the tape (and of course wash your hands because active mould is nasty stuff).

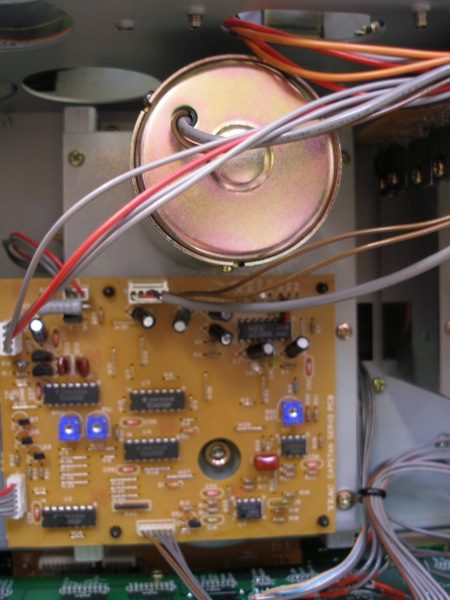

When we receive mouldy tape we place it in a sealed bag filled with desiccating silica gel. The silica gel helps to absorb the tape's moisture and de-fertilises the mould's 'living environment'.

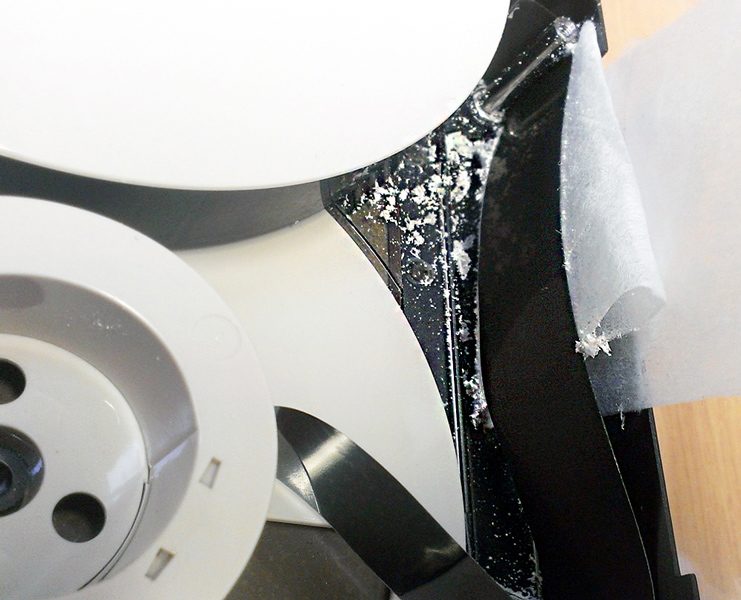

When the mould becomes dormant it will appear white and dusty, and is relatively easy to treat at this stage. We use brushes, vacuums with HEPA filters and cleaning solutions such as hydrogen peroxide to clean the tape.

Treatment should be conducted in a controlled environment using the appropriate health protections such as masks and gloves because mould can be very damaging for health.

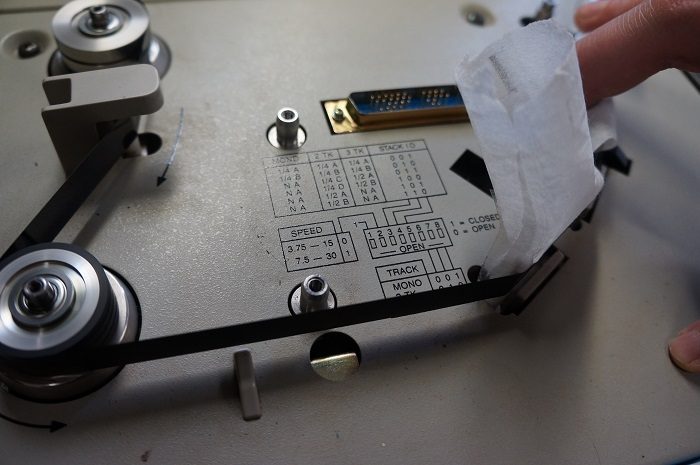

All machines used to playback mouldy tape are cleaned thoroughly after use - even tapes with dormant mould still carry the risk of infection.

Most tapes-infested with mould are treatable and can be effectively played back following the appropriate treatment procedures. Occasionally mould growth is so extensive however that it damages the binder irreparably. Mould can also exacerbate other problems associated with impaired tape, such as binder hydrolysis.

When it comes to tape mould the message is simple: it is a serious problem which poses a significant risk to the integrity of your collection.

If you do find mould on your tapes all is not lost. With careful, specialised treatment the material can be recovered. Action does need to be taken promptly however in order to salvage the tape and prevent the spread of further infection.

Feel free to contact us if you want to talk about your audio or video tapes that may need treatment or assessment.