Hustwit's Eno

As I write, just before 17.00 GMT / 12.00 EST, 24th January 2025, Anamorph.com are about to go live with the 24hour global streaming premiere of creative film maker Gary Hustwit's unique documentary feature 'Eno'.

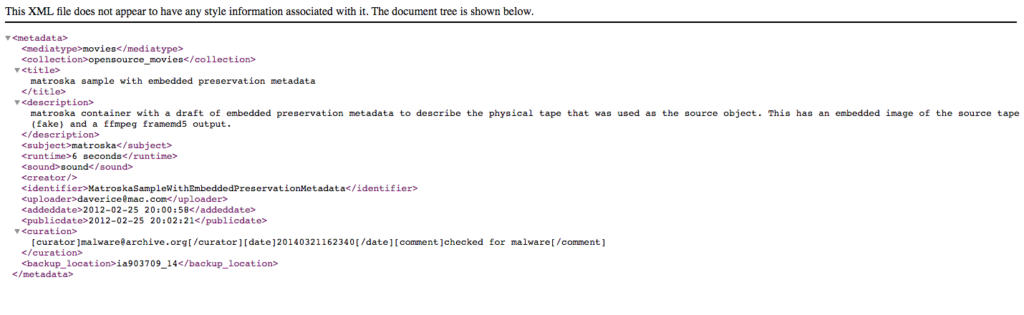

Echoing Brian Eno's long-running explorations of generative technology in composition, Hustwit and digital artist Brendan Hawes have created Brain One - a generative software system to make and re-make a feature film that's different every time it screens.

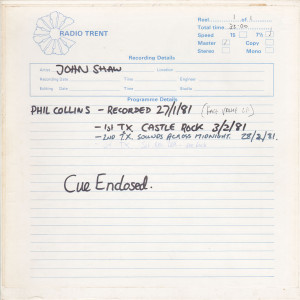

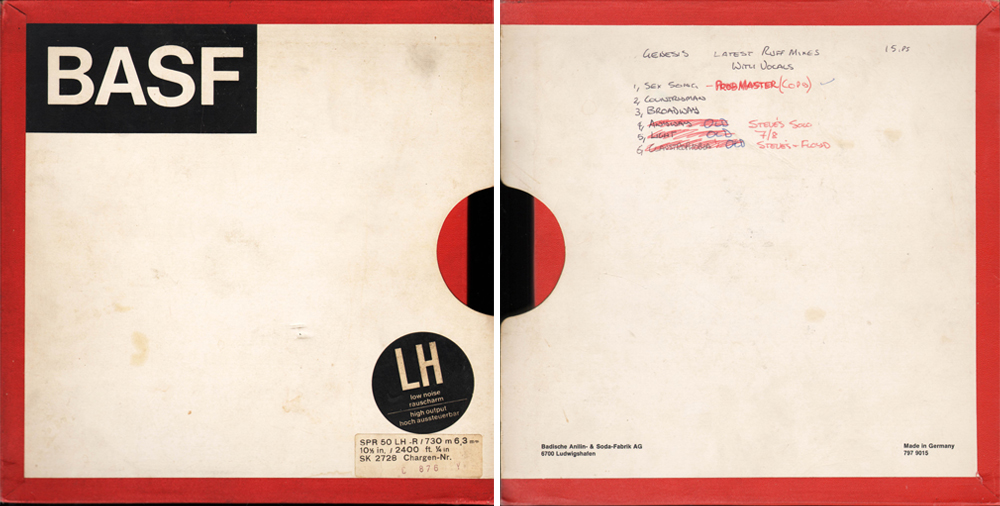

Each unique iteration of 'Eno' is assembled dynamically from a pool of scenes (c. 10 hours-worth in total) edited by Gary and his team from over 500 hours of Brian Eno's personal video archive and 30+ hours of in-depth interview footage.

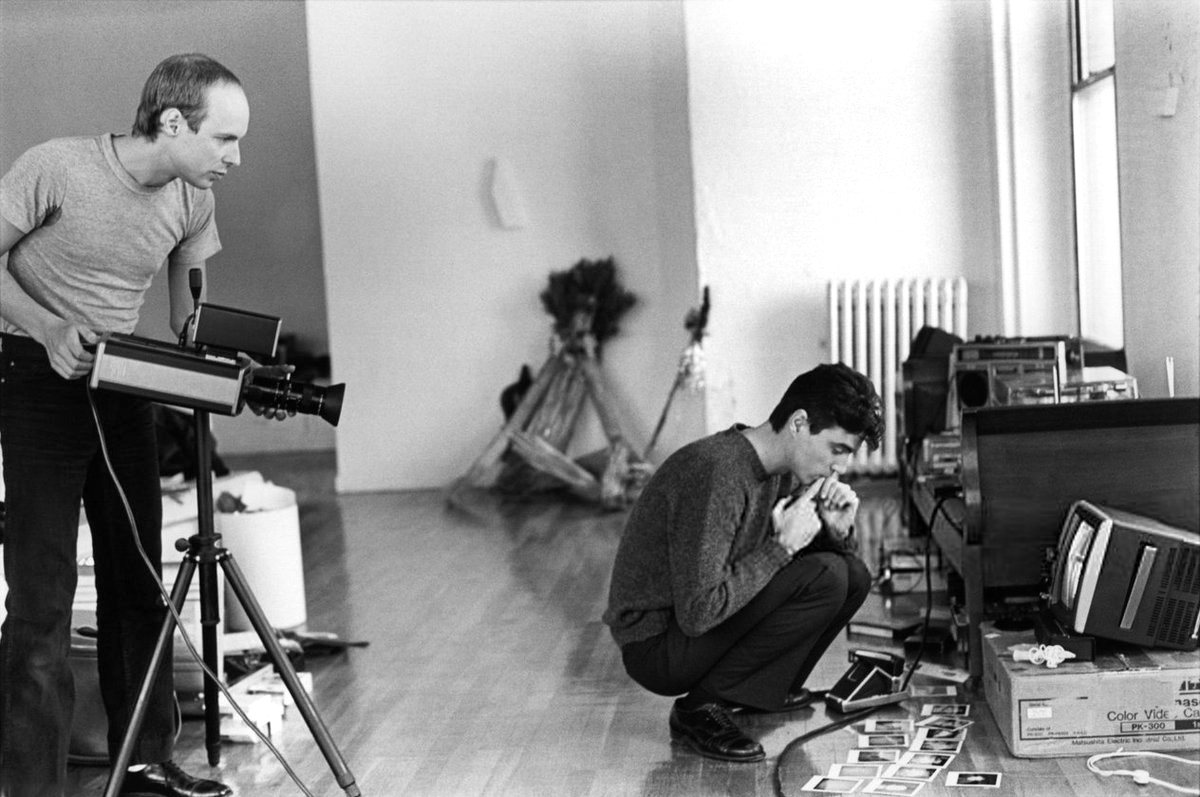

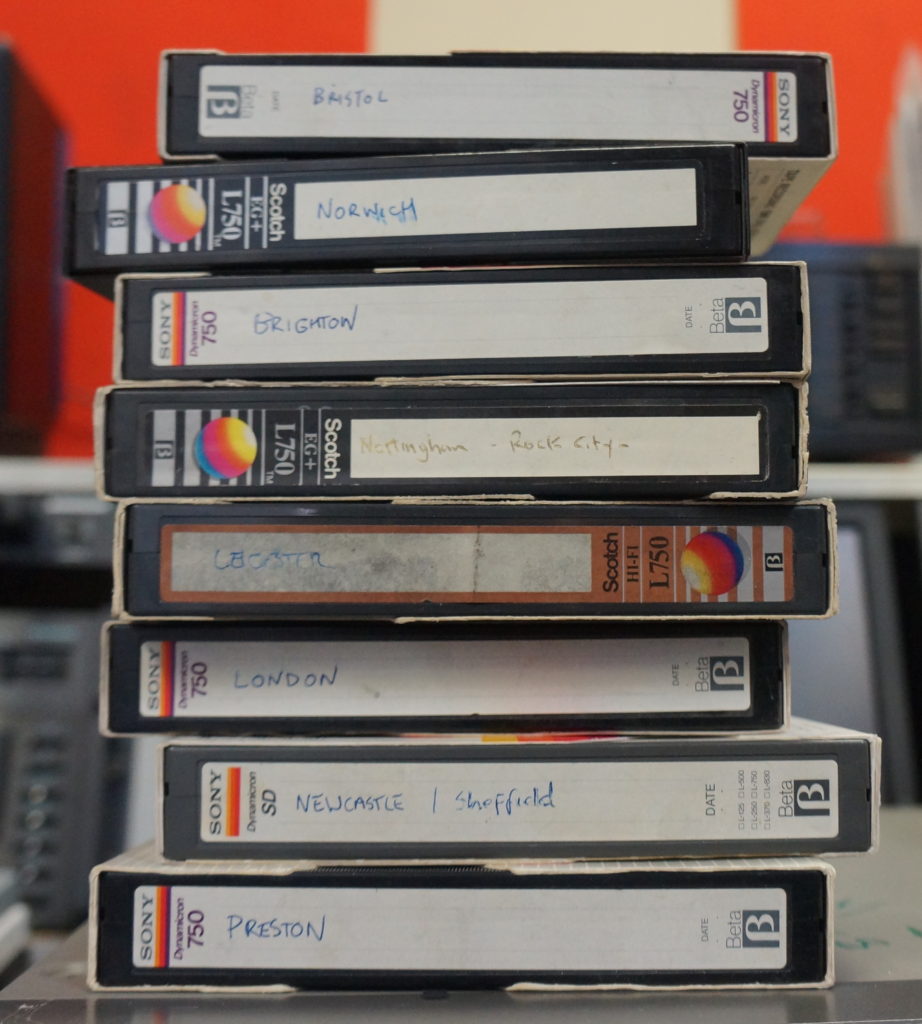

Greatbear became involved in summer 2022 when, working with independent archivist Alex Wilson, Gary delivered to us by hand the boxes containing 118 video tapes from Brian Eno’s personal archive, mostly in U-matic format.

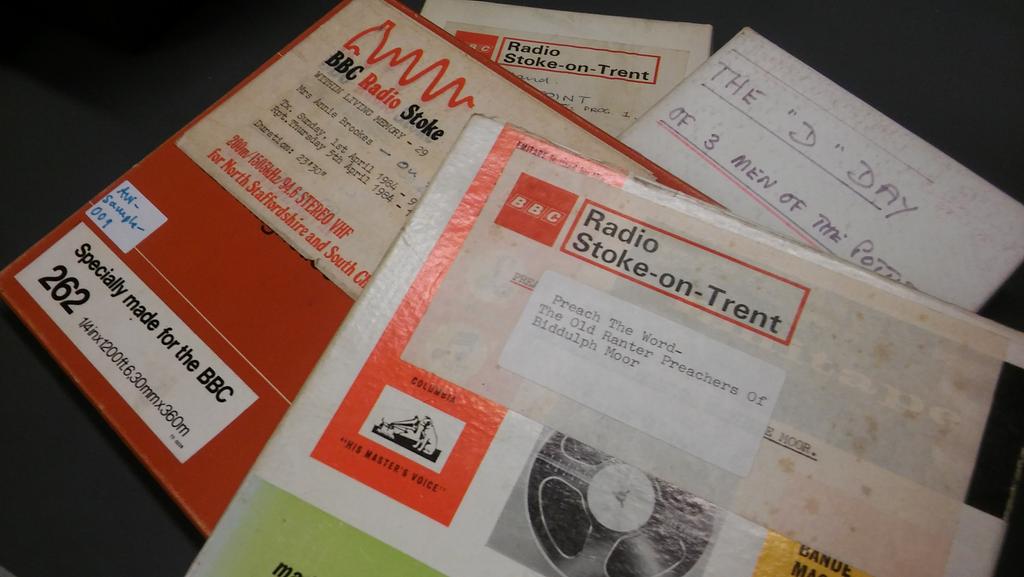

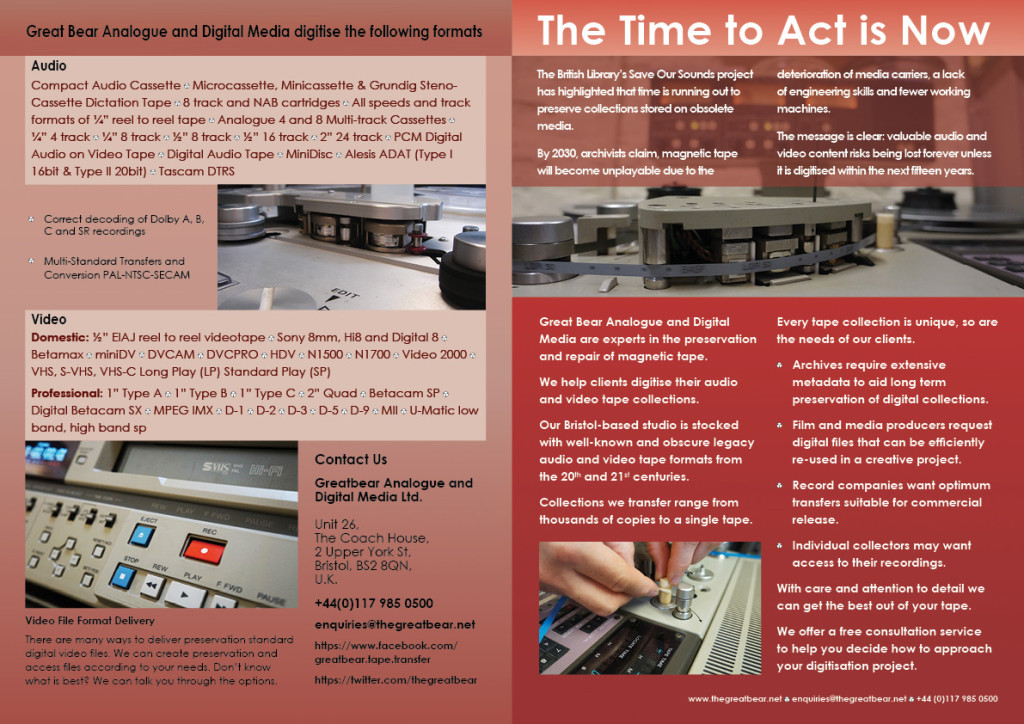

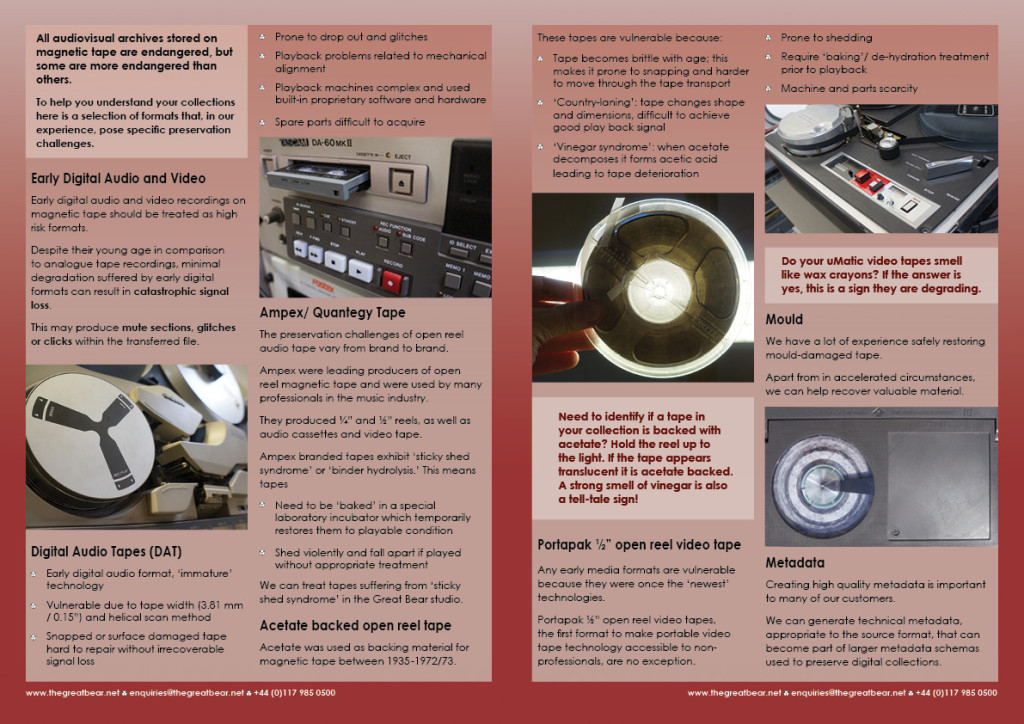

U-matic was an early, ¾ inch analogue videocassette format, primarily used in industrial, educational and news-gathering contexts in the 1970s – '80s.

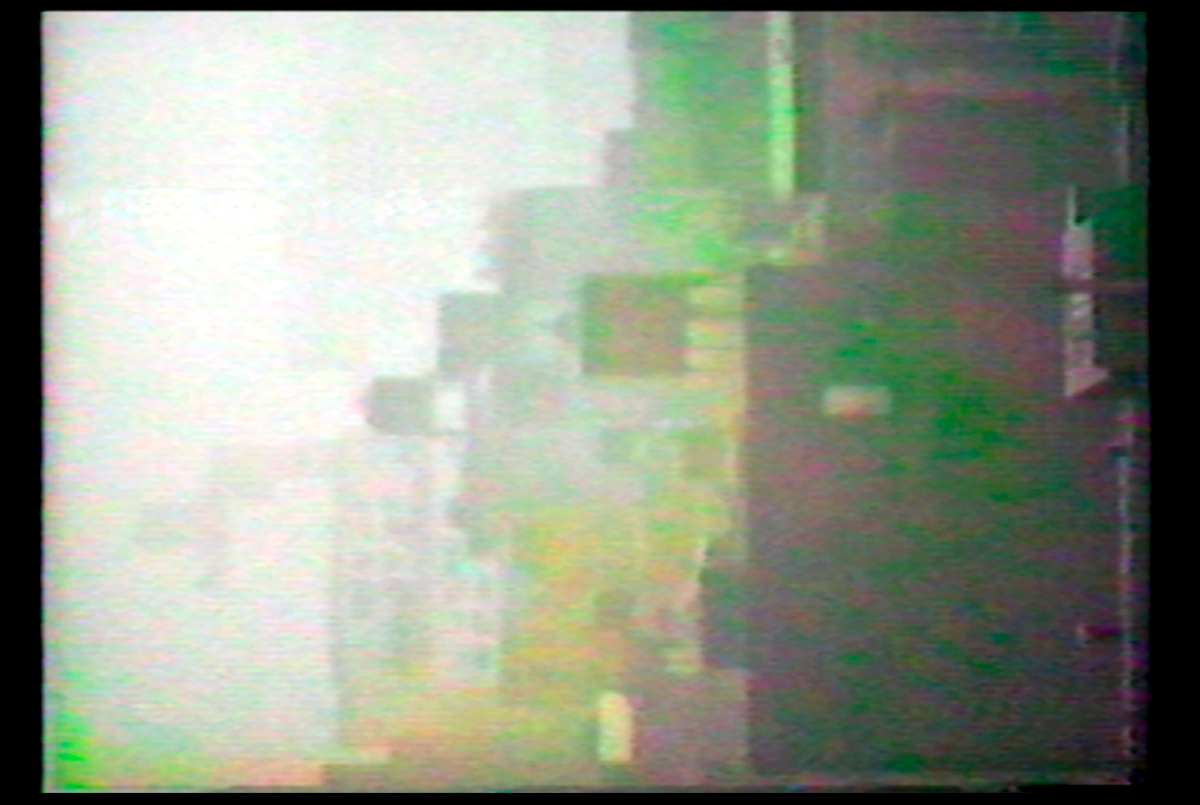

In his first experiments with the format, Eno placed the camera on its side on his window sill (having no tripod) and filmed the Manhattan skyline over many hours, burning out the camera's colour tubes and the playing further with the camera's basic settings to produce the meditative, odd-coloured 'portraits' (video paintings) that became his Mistaken Memories of Mediaeval Manhattan single monitor piece (1980).

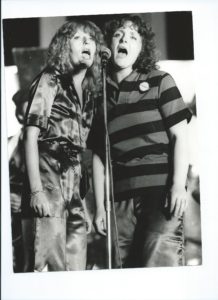

2 stills from footage created by Eno for Mistaken Memories of Mediaeval Manhattan

To view these early works, tv monitors would need to be turned through 90 degrees and rested on their side, so that the image would appear vertically, rather than in traditional landscape format. With the advent of mobile phone video, we are now much more used to viewing moving images in portrait format. Back in the late ‘70s & early ‘80s, when Eno was making these pieces, it was his intention to sidestep the theatricality of the widescreen in an attempt to remove the expectation that something dramatic should happen.

The Revenge of the Intuitive

In the age of 8K Ultra-HD, why do we still get excited about making authentic, accurate new transfers of grainy, distorted, distinctly lo-fi U-matic video footage? In his Wired essay The Revenge of the Intuitive, Eno finds depth and personality in what he describes as

“the revenge of traditional media. Even the "weaknesses" or the limits of these tools become part of the vocabulary of culture.

…These limitations tell you something about the context of the work, where it sits in time, and by invoking that world they deepen the resonances of the work itself.Since so much of our experience is mediated in some way or another, we have deep sensitivities to the signatures of different media. Artists play with these sensitivities, digesting the new and shifting the old. In the end, the characteristic forms of a tool's or medium's distortion, of its weakness and limitations, become sources of emotional meaning and intimacy.”

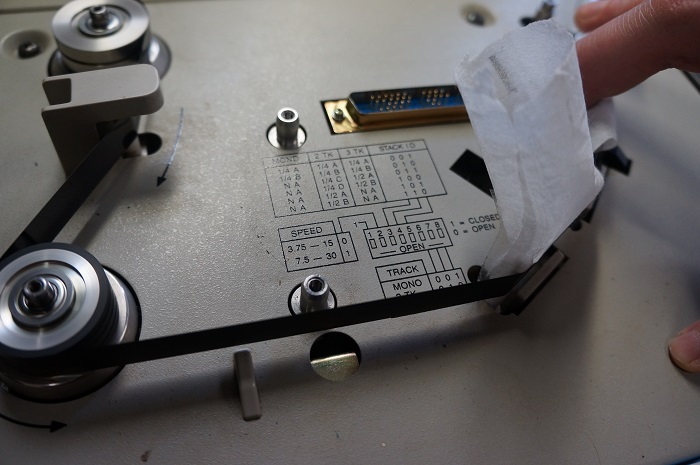

Sticky Shed & Wax Crayons - working with 25 - 45 year old U-matic tape

Owing to their age, each of the U-matic tapes from Eno’s archive that we digitised at Greatbear came with some form of deterioration and challenge to transfer.

Firstly, the Ampex 187 KCA-30 and KCA-60 tapes all needed controlled dehydration treatment (‘baking’) in the incubator at 52 degrees centigrade for up to 48hours to reverse the effects of binder hydrolysis, which is an inevitable consequence of age in this particular formulation of tape.

Binder hydrolysis leads to “sticky shed syndrome”, where tape will stick to itself as it is unwound or played, causing irreparable damage to the magnetic information.

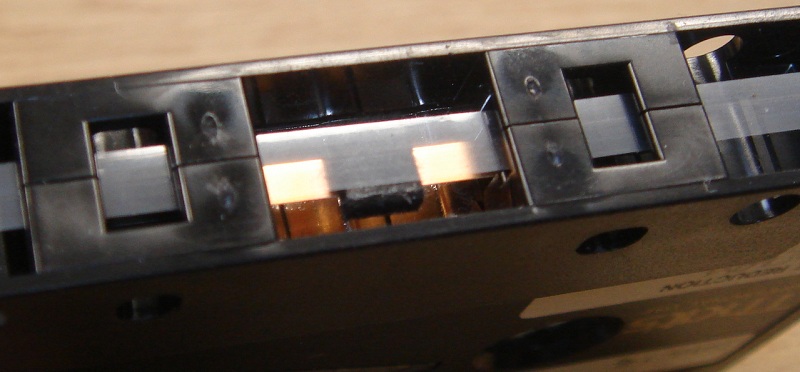

Sony KCS-20 U-matic tape box

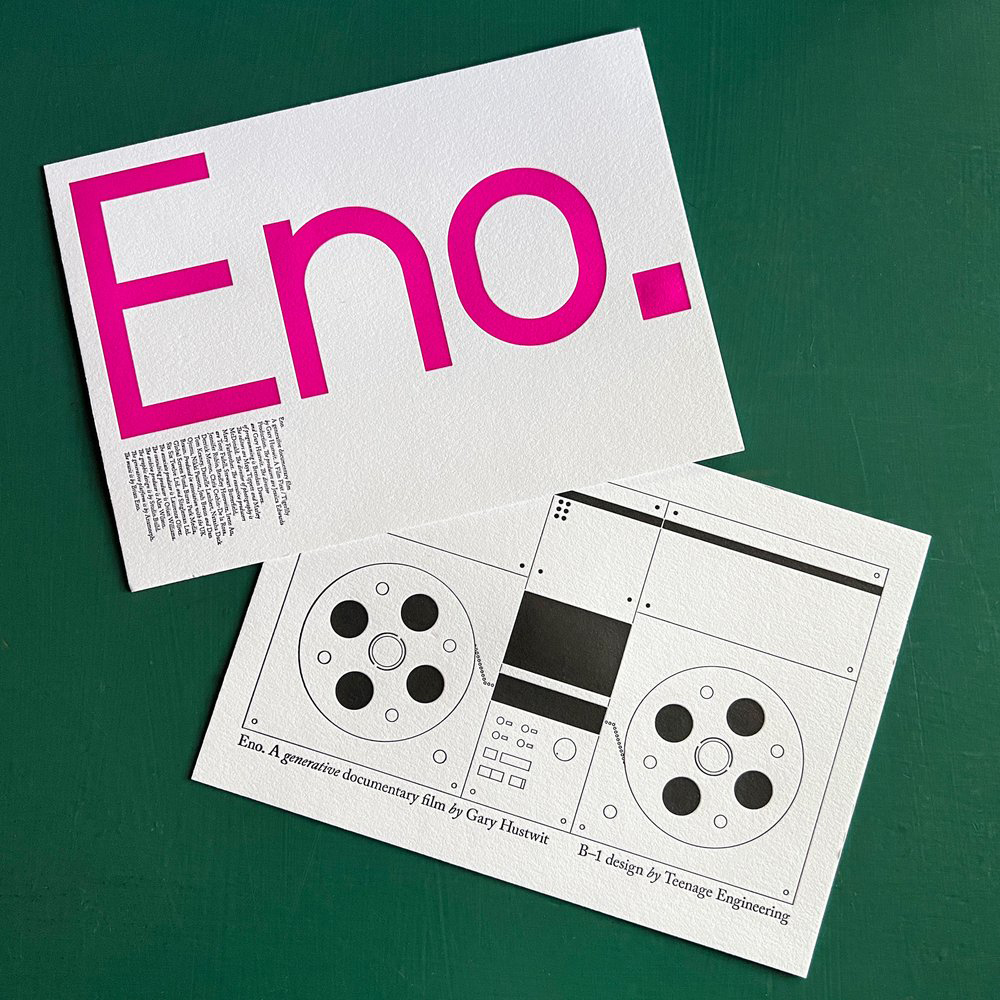

Letterpress mini posters including drawing of “Brain One” machine used to create the film at live screenings, designed by Teenage Engineering. Visit www.ohyouprettythings.com

The Sony KCS-10 and KCS-20 tapes, and the Sony KCA-30 and KCA-60 tapes, (while less prone to typical binder hydrolysis that can be treated by ‘baking’), had fallen prey to their own peculiar chemical degradation, emitting the familiar smell of wax crayons from the breakdown of medium chain fatty acids in their formulation.

This breakdown can lead to low RF from the tape and frequent head clogs in the playback machine, causing visual artefacts and potential damage to the tape’s surface. Multiple cleaning passes were needed before these could be digitised.

Several of the Sony U-matics arrived stuck at the end or part-way through the tape. This is often due to excess friction in the tape path through the cassette, caused by gradual loss of lubricant. Attempting to play these could have led to stretching or other damage, and so we needed to gently rewind these by hand before we could play them at all.

A similar issue had befallen the some of Scotch 3M MBU tapes in the collection, so they got the manual rewind treatment too. As they degrade, Scotch 3M U-matics tend to exude a white crystalline powder. We didn’t find RF so severely affected in these tapes, but the exudate can clog playback heads and potentially scratch the tape. As with the Sony tapes, we treated these with multiple cleaning passes, while vacuuming the residue.

Additionally a minority of tapes exhibited some mould growth along the edge of the tape pack, which had affected the control track, leading to image instability.

None of these issues were unique to this collection of tapes. While Eno is well-known for being more interested in his next project than his past work, it is almost impossible to avoid some deterioration in tapes of this age. Carefully tending to fragile tape is all part of our conservation process. Thanks to Hustwit and Eno for entrusting this precious audio-visual heritage to us in the creation of their forward-looking project.

Look out for new performances of Eno is cinemas: as an endlessly re-configured and re-configurable piece, it can never grow old!