The oldest tape we have received at the Greatbear is a spool of paper backed magnetic tape, c.1948-1950. It’s pretty rare to be sent paper-backed tape, and we have been on a bit of adventure trying to find more about its history. On our trail we found a tale of war, economics, industry and invention as we chased the story of the ‘magnetic ribbon’.

The first thing to recount is how the development of magnetic tape in the 1930s and 1940s is enmeshed with events in the Second World War. The Germans were pioneers of magnetic tape, and in 1935 AEG demonstrated the Magnetophon, the first ever tape recorder. The Germans continued to develop magnetic tape, but as the 1930s wore on and war declared, the fruits of technological invention were not widely shared – establishing sophisticated telecommunication systems was essential for the ‘war effort’ on both sides.

Towards the end of the war when the Allies liberated the towns and cities of Europe, they liberated its magnetic tape recording equipment too. Don Rushin writes in ‘The Magic of Magnetic Tape.’

‘By late 1944, the World War II Allies were aware of the magnetic recorder developed by German engineers, a recorder that used an iron-powder-coated paper tape, which achieved much better sound quality that was possible with phonograph discs. A young Signal Corps technician, Jack Mullin, became part of a scavenging team assigned to follow the retreating German army and to pick up items of electronic interest. He found parts of recorders used in the field, two working tape recorders and a library of tapes in the studios of Radio Frankfurt in Bad Nauheim.’

In the United States in WW2, significant resources were used to develop magnetic tape. ‘With money no object and the necessity of adequate recording devices for the military, developments moved at a brisker pace’, writes Mark Mooney.

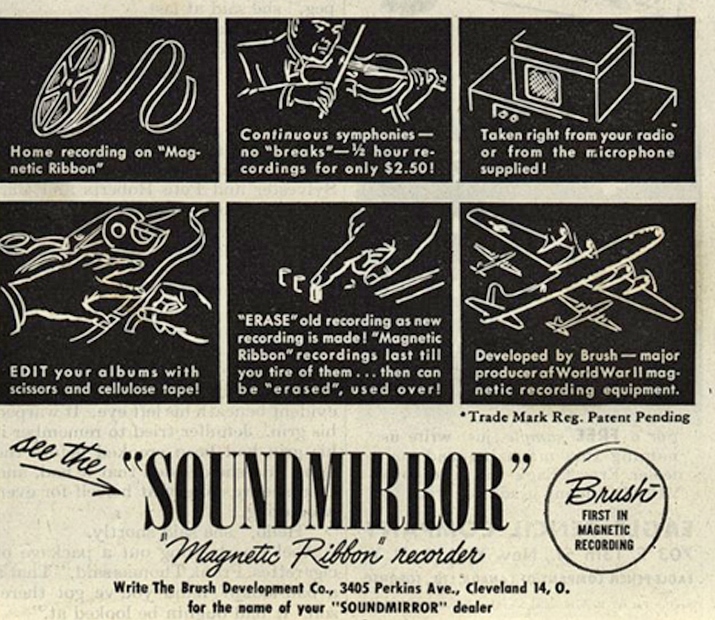

This where our paper tape comes into the equation, courtesy of Polish-born inventor Semi J. Begun. Begun began working for the Brush Development Company in 1938, who were one of the companies contracted to develop magnetic tape for the US Navy during the war. In his position at Brush Begun invented the ‘Sound Mirror.’ Developed in 1939-1940 but released on the market in 1946, it was the first magnetic tape recorder to be sold commercially in the US post WW2.

As the post-war rush to capitalise on an emerging consumer market gathered apace, companies such as 3M developed their own magnetic tapes. Paper backed magnetic tape was superseded toward the end of the 1940s by plastic tape, making a short but significant appearance in the history of recording media.

This however is a story of magnetic tape in the US, and our tape was recorded in England, so the mystery of the paper tape has not been solved. Around the rim of the rusted spool it states that it is ‘Licensed by the Brush Development Co U.S.A’, ‘Made in England’, ‘Patents Pending’ and ‘Thermionic Products Ltd.’

Thermionic were the British company who acquired the license to build the Soundmirror in 1948. Barry M Jones, who has collected a wider history of the British tape recorder, home studio and studio recording industries writes, ‘[Soundmirror] was the first British-built domestic tape-recorder, whereas the first British built-and-designed tape recorder was the Wright & Weaire, which appeared a few weeks later. Production began in autumn 1948 but the quality of the paper tape meant it shedded oxide too readily and clogged the heads!’

Production of the Soundmirrors continued to late 1954 so it is possible to date the tape as being recorded some time between 1948 and 1958. The weight of the spool and the tape is surprisingly heavy, the tape incredibly fragile, marking its passage through time with signs of corrosion and wear. It is a beautiful object, as many of the tapes we get are, that is entwined with the social histories of media, invention, economy and everyday life.