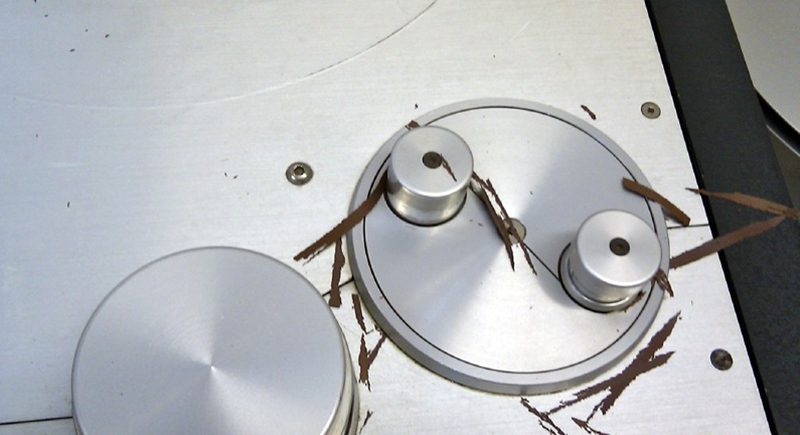

reel-to-reel tape: extreme delamination

The binder is crucial part of the composition of audio and video magnetic tape. It holds the iron oxide magnetisable coating on to its plastic carrier and facilitates its transport through the playback mechanism. It is also, however, 'universally agreed that with modern PET-based tape the binder is the weak link, and is generally the part of the tape which creates the most problems,' according to a UNESCO report.

There is of course no 'one-size-fits-all' answer to treating problems with tape binder. Each tape will have a unique manufacturing, playback and storage history that will shape its current condition, so restoration solutions need to respond on a case-by-case basis.

Detailed below are some of the common and diverse things that can go wrong with the tape binder, and how Greatbear can help restore your tape to a playable condition.

Binder Hydrolysis aka Sticky Shed Syndrome and Tape Baking

Probably the most well-known fault that can occur with magnetic tape is binder hydrolysis.

As its name indicates, hydrolysis is a chemical process caused by the absorption of water present in the tape's storage environment. In certain brands of tape, most notably Ampex, the binder polymers used in magnetic tape construction are broken apart as they react with water, which causes damage to the tape.

There are other theories about what happens when tapes get sticky and shed. Dietrich Schüller conducted interviews with experts of former tape manufacturers based in Germany, and concluded that 'the chemical recipe is the basis, if not the guarantee, for tape quality and stability. The production process, is equally, if not more essential.'

Schüller's research explains how the manufacture of tapes required a delicate balance between speed and precision, encompassing issues such as coating speed, proper dispersion of components, temperature and pressure of calendars. Professional tapes were produced at a rate between 100-200 metres per second (m/s). In the final stage of tape manufacture 'production speed reached 1000 m/s. This required the cross linking of binder components during the coating process.' This uneven distribution, Schüller found, sometimes led to sticky areas. [1]

Tapes exhibiting sticky shed syndrome will stick to the tape pack as they are unwound. These tapes are extremely vulnerable and need effective treatment before they can be played back. Playing a sticky tape is likely to damage the tape. It will also result in head clogs, stick-slip playback and seizure of the tape transport. In extreme cases the tape may fall apart entirely.

Although a serious problem, binder hydrolysis can be treated. Tape baking at controlled temperatures can temporarily improve binder integrity, helping to restore tape to a playable condition. In our studios we use a Thermo Scientific Heraeus B20 laboratory incubator for this process.

Lubricant Loss

Lubricants are a crucial part of the tape binder's composition, required to help the tape move smoothly through the transport. 'The quantity of lubricant is greater for video than for audio because of the higher writing and reading speeds.' [2]

Over time, the level of lubricant in the tape decreases because lubricants are partially consumed every time the tape is played. Lubricant levels decrease over time even if they are unplayed, particularly if they have not been stored in appropriate conditions for passive preservation.

As you will imagine, playing a tape back that has lost its lubricant carries with it certain risks. The tape may seize in the transport as a result of high friction, and the magnetic coating may be torn off the tape backing as it moves at a high speed past the tape head.

In cases where there is extreme lubricant loss we can apply a lubricant to help ease the tape through the transport. On the whole we are keen to use treatment methods that are as non-intrusive as possible, so such measures are kept to a minimum: 're-lubrication [...] must be seen very critically, as it is impossible to restrict added lubricants to the small amounts actually needed. Superfluous lubricants are difficult to remove from the tape guides, heads, and capstan and may interact with other tapes played on those machines at a later date.' [3]

A lack of lubricant can often result in dry shedding. This produces a dusty (rather than sticky) residue that is deposited on the capstan belts and pinch rollers as the tape moves through the transport. Dry shedding can be treated by consistently cleaning the tape until it reaches a point where it can be played back without shedding again. You can read more about this method here.

[1] Dietrich Schüller, 'Magnetic Tape Stability: Talking to Experts of Former Tape Manufacturers.' IASA Journal, Vol. 42, Jan 2014, 32-37, 34.

[2] IASA-TC-05, 'Handling and Storage of Audio and Video Carriers,' 20.

[3] IASA-TC-05, 'Handling and Storage of Audio and Video Carriers,' 20.