At the beginning of 2015, the British Library launched the landmark Save Our Sounds project.

The press release explained:

‘The nation’s sound collections are under threat, both from physical degradation and as the means of playing them disappear from production. Archival consensus internationally is that we have approximately 15 years in which to save our sound collections by digitising them before they become unreadable and are effectively lost.’

While such news might (understandably) usher in a culture of utter panic, and, let’s face it, you’d have to have a strong disposition if you were charged with managing the Save Our Sounds project, the British Library are responding with stoic pragmatism. They are currently undertaking a national audit to map the conditions of sound archives which your organisation can contribute to.

Yet whatever way you look at it, there is need to take action to migrate any collections currently stored on obsolete media, particular if you are part of a small organisation with limited resources. The reality is it will become more expensive to transfer material as we move closer to 2030. The British Library project relates particularly to audio heritage, but the same principles apply to audiovisual collections too.

Yes that rumbling you can hear is the sound of archivists the world over engaged in flurry of selection and appraisal activities….

Extinction

One of the most interesting things about discussions of obsolete media is that the question of operability is often framed as a matter of life or death.

Formats are graded according to their ‘endangered statuses’ in more or less explicit terms, as demonstrated on this Video Preservation website which offers the following ‘obsolescence ratings’:

‘Extinct: Only one or two playback machines may exist at specialist laboratories. The tape itself is more than 20 years old.

Critically endangered: There is a small population of ageing playback machinery, with no or little engineering or manufacturing support. Anecdotal evidence indicates that there are fewer working machine-hours than total population of tapes. Tapes may range in age from 40 years to 10 years.

Endangered: The machine population may be robust, but the manufacture of the machinery has stopped. Manufacturing support for the machines and the tapes becomes unavailable. The tapes are often less expensive, and more vulnerable to deterioration.

Threatened: The playback machines are available; however, either the tape format itself is unstable or has less integrity than other available formats, or it is known that a more popular or updated format will be replacing this one in a short period of time.

Vulnerable: This is a current but highly proprietary format.

Lower risk: This format will be in use over the next five years (1998-2002).’

The ratings on the video preservation website were made over ten years ago. A more comprehensive and regularly updated resource to consult is the Preservation Self-Assessment Program (PSAP), ‘a free online tool that helps collection managers prioritize efforts to improve conditions of collections. Through guided evaluation of materials, storage/exhibit environments, and institutional policies, the PSAP produces reports on the factors that impact the health of cultural heritage materials, and defines the points from which to begin care.’ As well as audiovisual media, the resource covers photo and image material, paper and book preservation. It also has advice about disaster planning, metadata, access and a comprehensive bibliography.

The good news is that fantastic resources do exist to help archivists make informed decisions about reformatting collections.

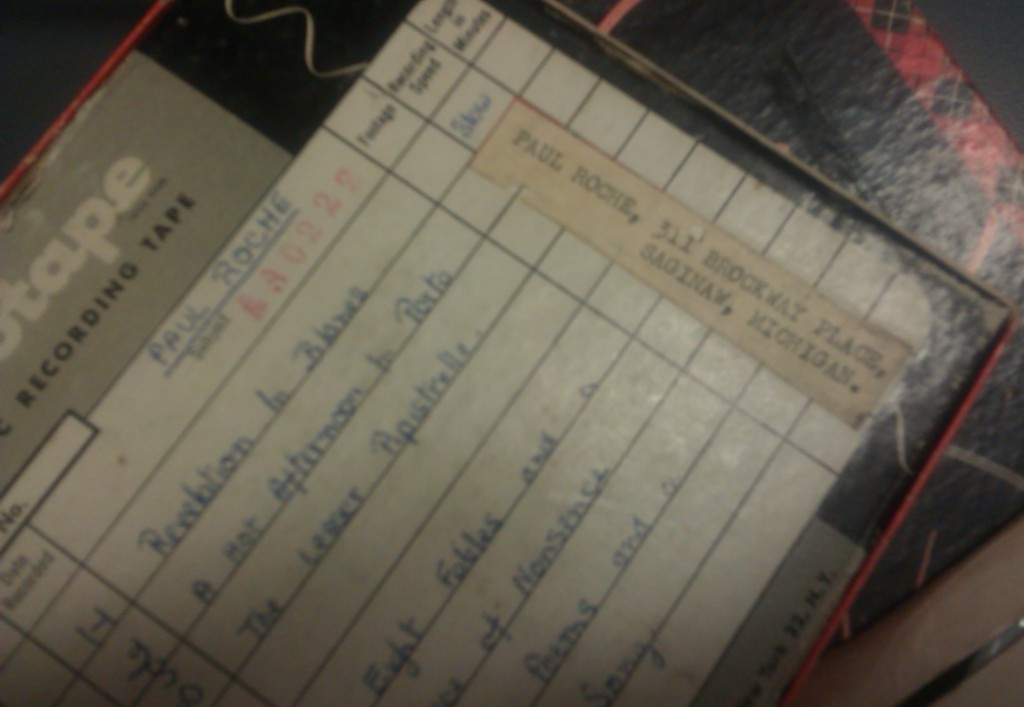

A Digital Compact Cassette

The bad news, of course, is that the problem faced by audiovisual archivists is a time-limited one, exacerbated no doubt by the fact that digital preservation practices on the ‘output end’ are far from stable. Finding machines to playback your Digital Compact Cassette collection, in other words, will only be a small part of the preservation puzzle. A life of file migrations in yet to be designed wrappers and content-management systems awaits all kinds of reformatted audiovisual media in their life-to-come as a digital archival object.

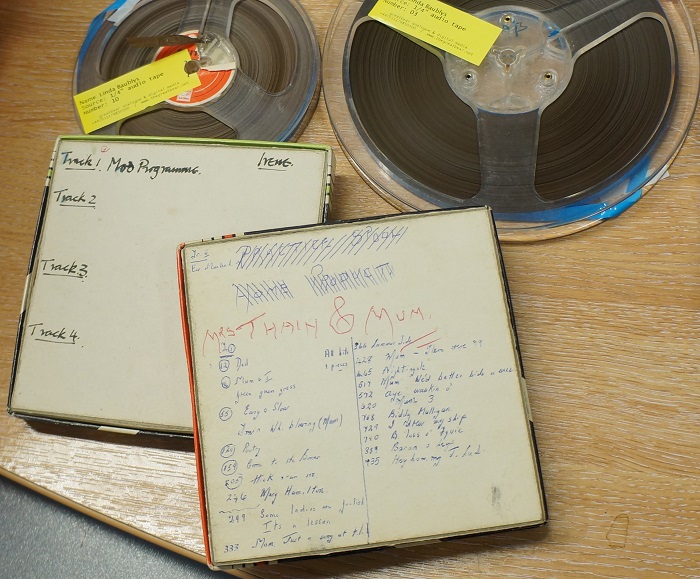

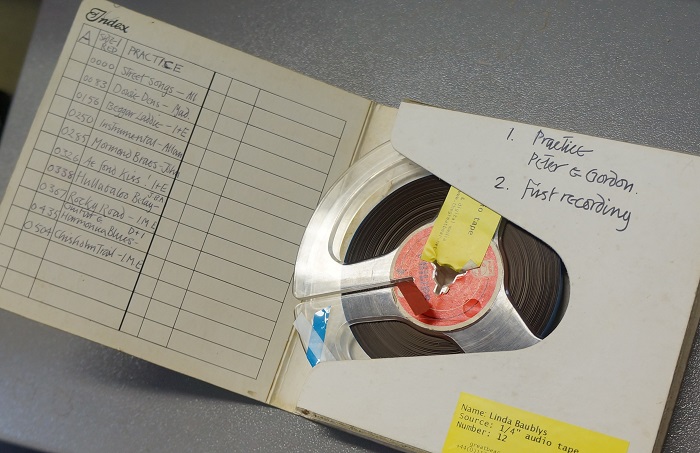

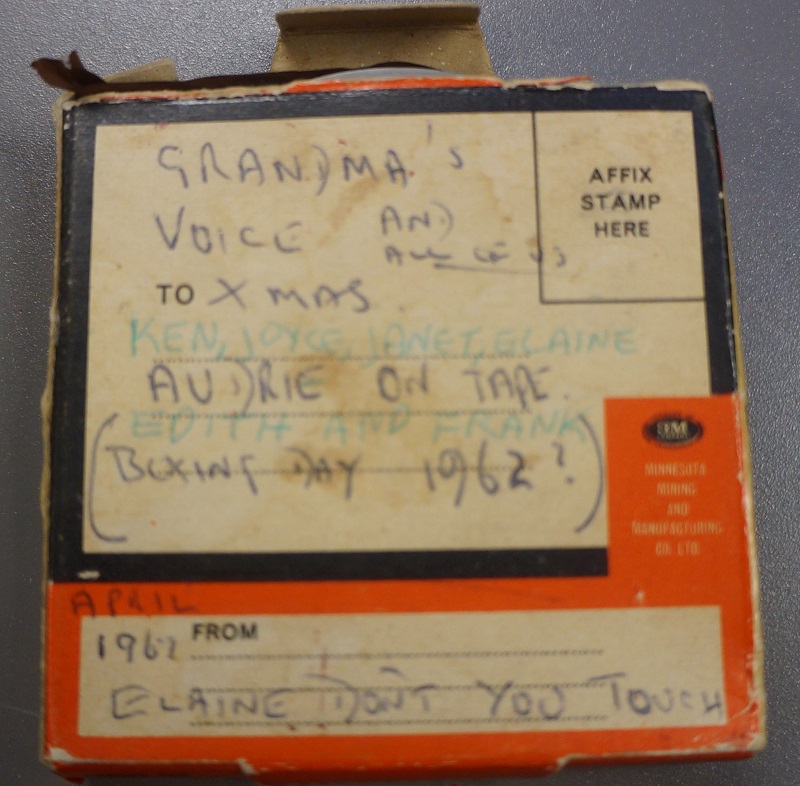

Depending on the ‘content value’ of any collection stored on obsolete media, vexed decisions will need to be made about what to keep and what to throw away at this clinical moment in the history of recorded sound.

Sounding the fifteen-year warning

At such a juncture, when the fifteen year warning has been sounded, perhaps we can pause for a second to reflect on the potential extinction of large swathes of audio visual memory.

If we accept that any kind of recording both contains memory (of a particular historical event, or performance) and helps us to remember as an aide-mémoire, what are the consequences when memory storage devices which are, according to UNESCO, ‘the primary records of the 20th and 21st centuries’, can no longer be played back?

These questions are of course profound, and emerge in response to what are consequential historical circumstances. They are questions that we will continue to ponder on the blog as we reflect on our own work transferring obsolete media, and maintaining the machines that play them back. There are no easy answers!

As the 2030 deadline looms, our audiovisual context is a sobering retort to critics who framed the widespread availability of digitisation technologies in the first decade of the 21st century as indicative of cultural malaise—evidence of a culture infatuated with its ‘past’, rather than concerned with inventing the ‘future’.

Perhaps we will come to understand the 00s as a point of audiovisual transition, when mechanical operators still functioned and tape was still in fairly good shape. When it was an easy, almost throw away decision to make a digital copy, rather than an immense preservation conundrum. So where once there was a glut of archival data—and the potential to produce it—is now the threat of abrupt and irreversible dropout.

Play those tapes back while you can!