At the recent Supernormal experimental arts and music festival held at Braziers Park, Oxfordshire, a number of artists were using analogue technologies to explore concepts that dovetail nicely with the work we do at Greatbear collecting, servicing and repairing obsolete tape machines.

Hacker Farm, for example, keep ‘obsolete tech and discarded, post-consumerist debris’ alive using ‘salvaged and the hand-soldered’ DIY electronics. Their performance was a kind-of technological haunting, the sound made when older machines are turned on and re-purposed in different eras. Eerie, decayed, pointless and mournful, the conceptual impetus behind Hacker Farm raises many questions that emerge from the rather simple desire to keep old technologies working. Such actions soon become strange and aesthetically challenging in the contemporary technological context, which actively reproduces obsolescence in the endless search for the new, fostering continuous wastefulness at the centre of industrial production.

Music by the Metre

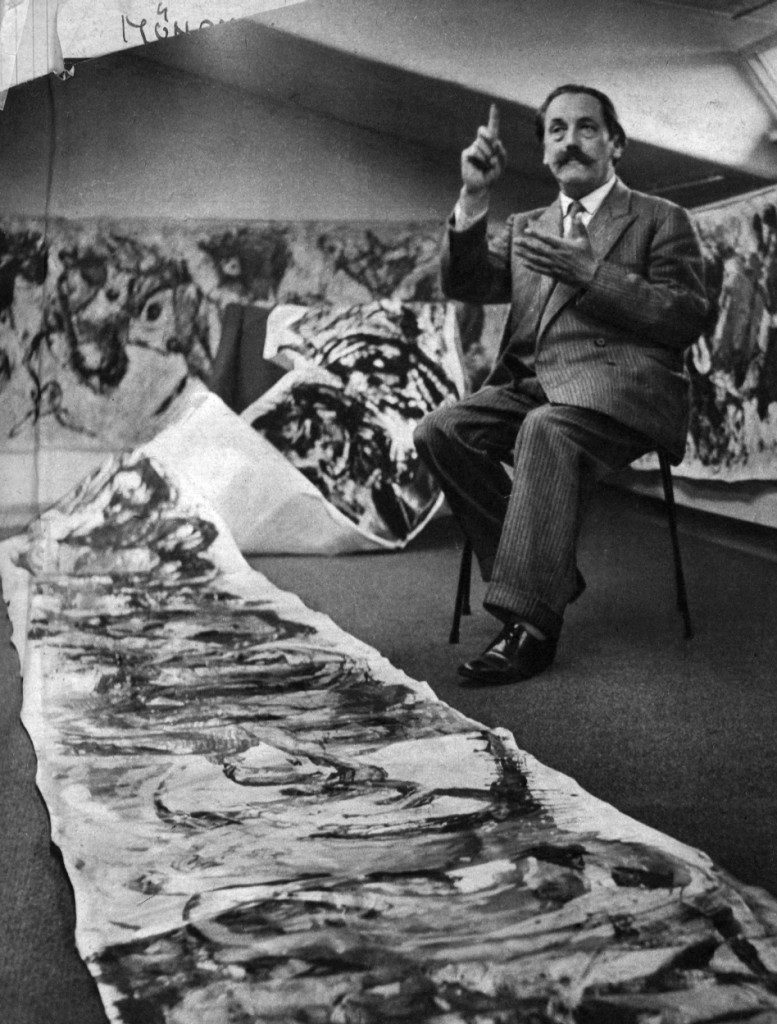

Another performance at the festival which engaged with analogue technologies was Graham Dunning’s Music by the Metre. The piece pays homage to Situationist Pinot-Gallizio‘s method of ‘Industrial Painting’ (1957-1959), in which the Italian artist created a 145 metre hand and spray painted canvas that was subsequently cut up and sold by the metre. The action, which attempted to destroy the perception of the sacrilegious art-object and transform it into something which could be mass-quantified and sold, aimed to challenge ‘the mental disease of banalisation’ inherent to what Guy Debord termed ‘the society of the spectacle.’

In Dunning’s contemporary piece he used spools of open reel tape to record a series of automated machines comprised of looping record players, synth drone, live environmental sound and tape loops. This tape is then cut by the artist in metre long segments, placed in see-through plastic bags and ‘sold’ on his temporary market stall used to record and present the work.

Dunning’s work exists in interesting tension with the ideas of Pinot-Gallizio, largely because of the different technological and aesthetic contexts the artists are responding to.

Pinot-Gallizio’s industrial painting aimed to challenge the role of art within a consumer society by accelerating its commodity status (mass-produced, uniform, quantified, art as redundant, art as part of the wall paper). Within Dunning’s piece, such a process of acceleration is not so readily available, particularly given the deep obsolescence of consumer-grade open reel tape in 2014, and, furthermore, its looming archival obsolescence (often cited at ’10-20 years‘ by archivists).

Within the contemporary context, open reel analogue tapes have become ornate and aestheticised in themselves because they have lost their function as an everyday, recordable mass blank media. When media lose their operating context they are transformed into objects of fascination and desire, as Claire Bishop pithily states in her Art Forum essay, ‘The Digital Divide’: ‘Today, no exhibition is complete without some form of bulky, obsolete technology—the gently clucking carousel of the slide-projector, or the whirring of an 8mm or 16mm film reel […] the sumptuous texture of indexical media is unquestionably seductive, but its desirability also arises from the impression that it is scarce, rare and precious.’

In reality, the impression of open reel to reel analogue tape’s rarity is however well justified, as manufacturers and distributors of magnetic tape are increasingly hard to find. Might there be something more complex and contradictory be going on in Dunning’s homage to Pinot-Gallizio? Could we understand it as a neat inversion of the mass-metred-object, doubly cut adrift from its historical (1950s-1970s) and technological operating context (the open reel tape recorder), the bag of tape is decelerated, existing as nothing other than art object. Stuffed messily in a plastic bag and displayed ready to be sold (if only by donation), the tape is both ugly and useless given its original and intended use. It is here Dunning’s and Pinot-Gallizio’s work converge, situated at different historical and temporal poles from which critique of the consumer society can be mounted: accelerated plenitude and decelerated exhaustion.

Analogue attachments

As a company that works with obsolete magnetic tape-based media, Greatbear has a vested interest in ensuring tapes and playback machines remain operational. Although our studio, with its stacks of long-forgotten machines, may look like a curious art installation to some, the tapes we migrate to digital files are not quite art objects…yet. Like Hacker Farm, we help to keep old media alive through careful processes of maintenance and repair.

From looking at how contemporary sound artists are engaging with analogue technologies, it is clear that the medium remains very much part of the message, as Marshall McLuhan would say, and that meaning becomes amplified, contorted or transformed depending on historical context, and media norms present within it.