In a 2012 report entitled ‘Preserving Sound and Moving Pictures’ for the Digital Preservation Coalition’s Technology Watch Report series, Richard Wright outlines the unique challenges involved in digitising audio and audiovisual material. ‘Preserving the quality of the digitized signal’ across a range of migration processes that can negotiate ‘cycles of lossy encoding, decoding and reformatting is one major digital preservation challenge for audiovisual files’ (1).

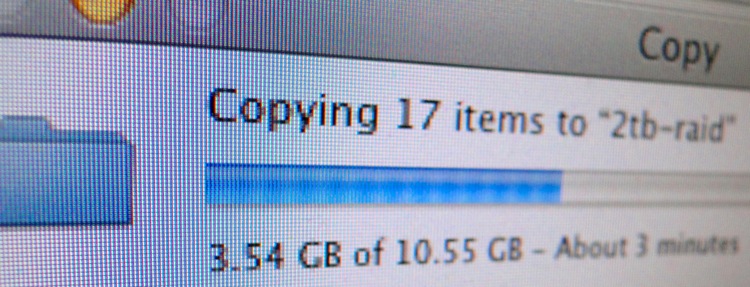

Wright highlights a key issue: understanding how data changes as it is played back, or moved from location to location, is important for thinking about digitisation as a long term project. When data is encoded, decoded or reformatted it alters shape, therefore potentially leading to a compromise in quality. This is a technical way of describing how elements of a data object are added to, taken away or otherwise transformed when they are played back across a range of systems and software that are different from the original data object.

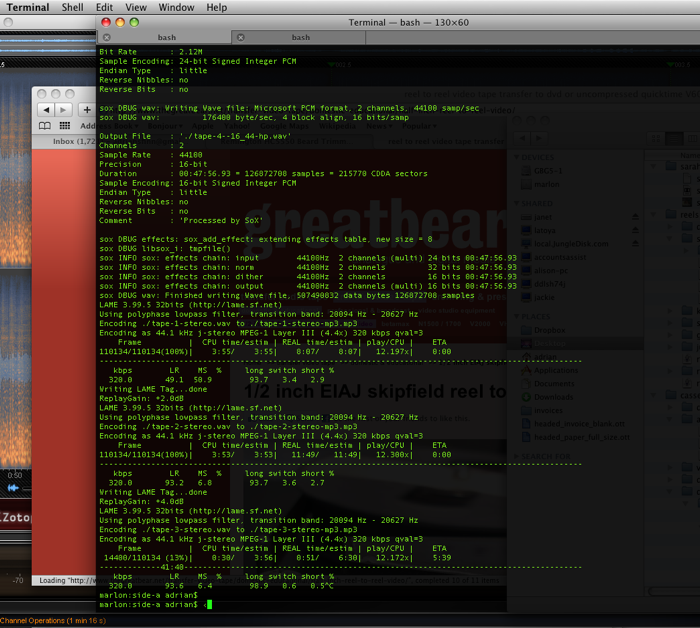

To think about this in terms which will be familiar to people today, imagine converting an uncompressed WAV into an MP3 file. You then burn your MP3s onto a CD as a WAV file so it will play back on your friend’s CD player. The WAV file you started off with is not the same as the WAV file you end up with – its been squished and squashed, and in terms of data storage, is far smaller. While smaller file size may be a bonus, the loss of quality isn’t. But this is what happens when files are encoded, decoded and reformatted.

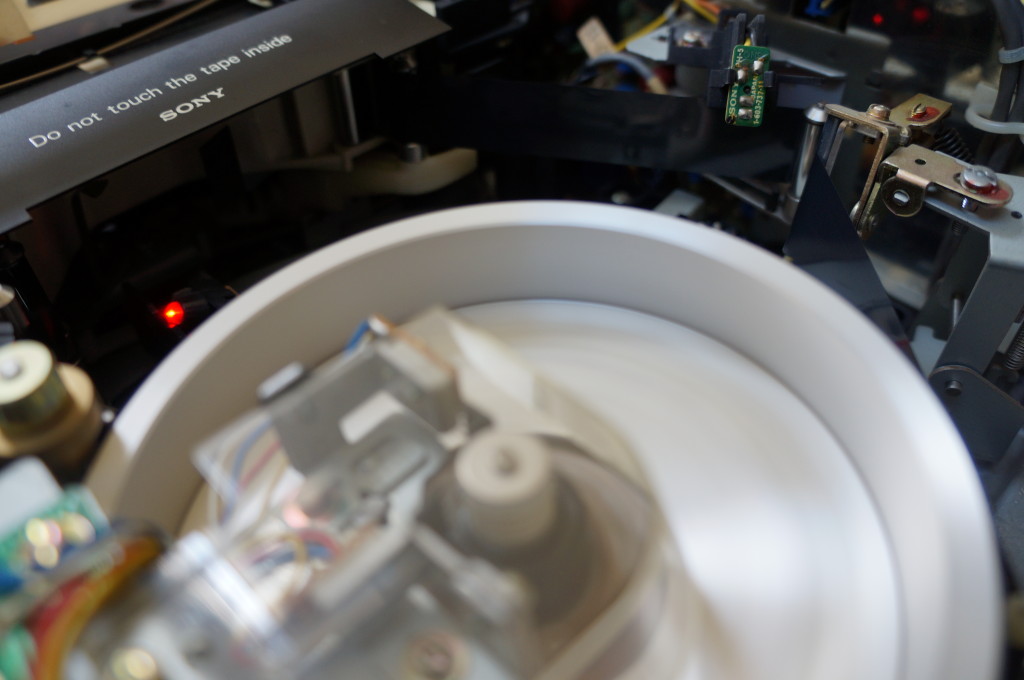

Subjecting data to multiple layers of encoding and decoding does not only apply to digital data. Take Betacam video for instance, a component analogue video format introduced by SONY in 1982. If your video was played back using composite output, the circuity within the Betacam video machine would have needed to encode it. The difference may have looked subtle, and you may not have even noticed any change, but the structure of the signal would be altered in a ‘lossy’ way and can not be recovered to it’s original form. The encoding of a component signal, which is split into two or more channels, to a composite signal, which essentially squashes the channels together, is comparable to the lossy compression applied to digital formats such as mp3 audio, mpeg2 video, etc.

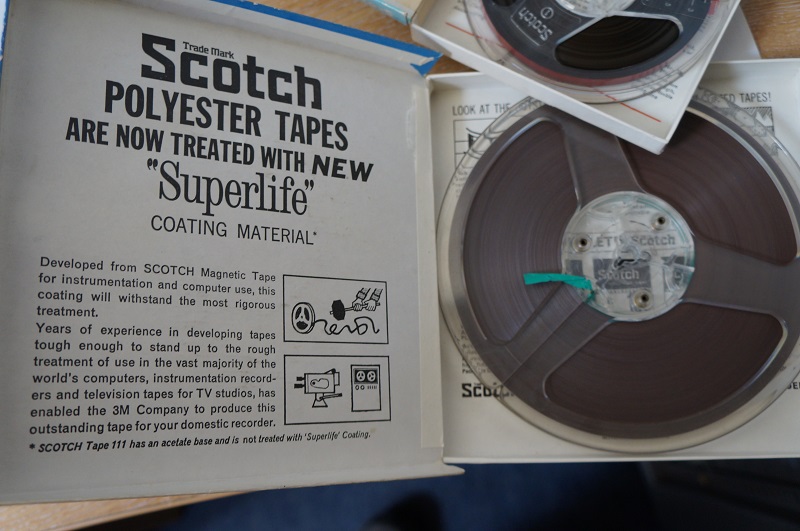

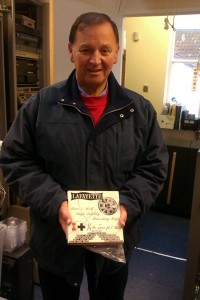

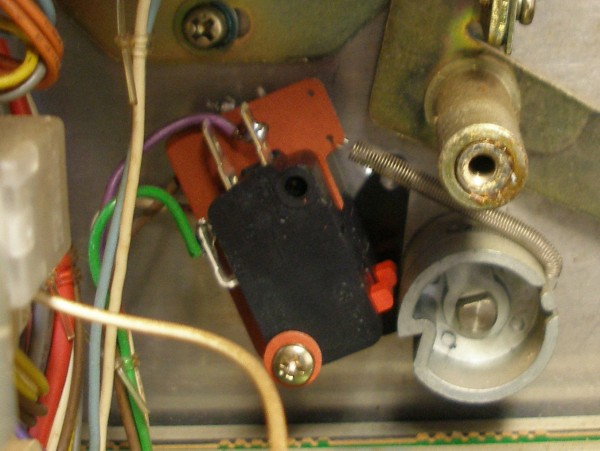

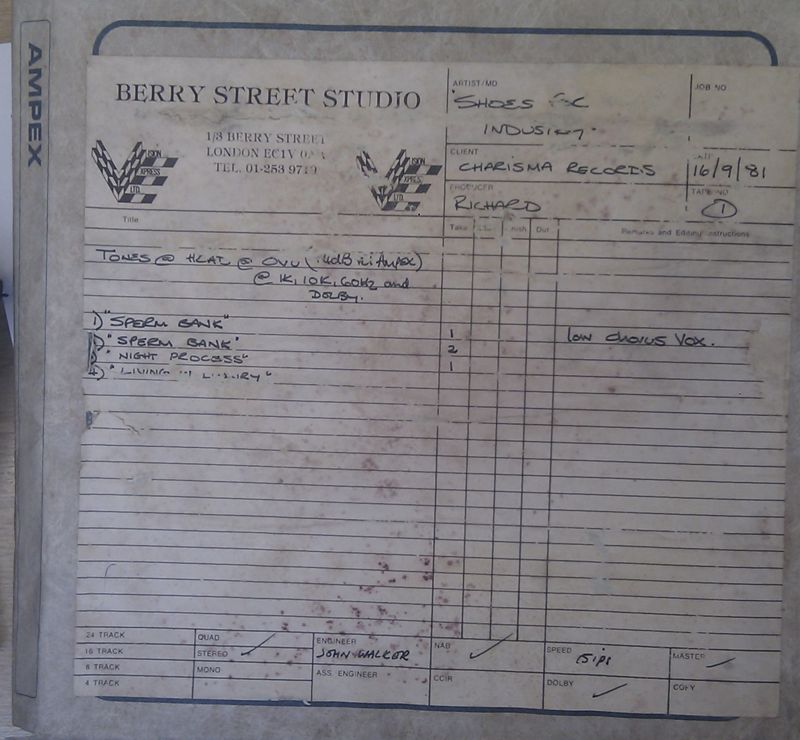

A central part of the work we do at Greatbear is to understand the changes that may have occurred to the signal over time, and try to minimise further losses in the digitisation process. We use a range of specialist equipment so we can carefully measure the quality of the analogue signal, including external time based correctors and wave form monitors. We also make educated decisions about which machine to play back tapes in line with what we expect the original recording was made on.

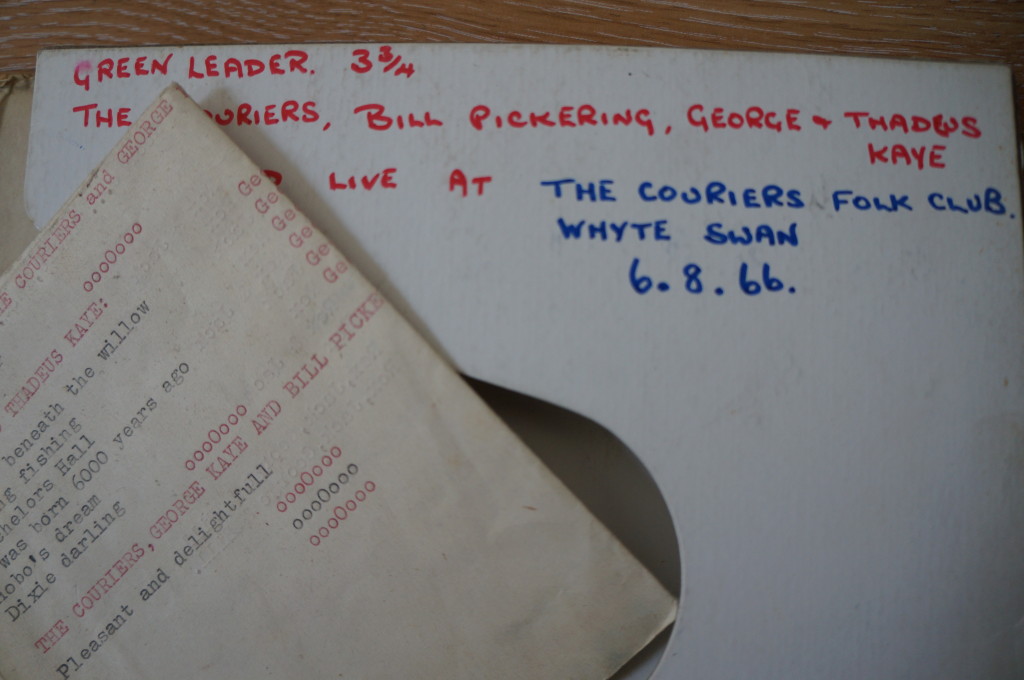

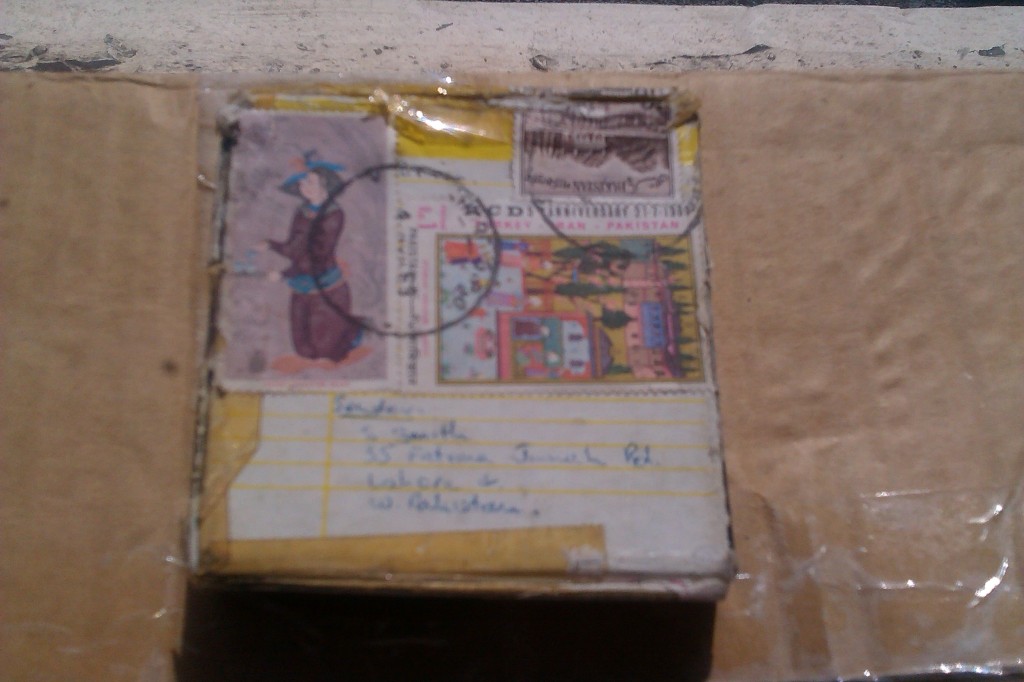

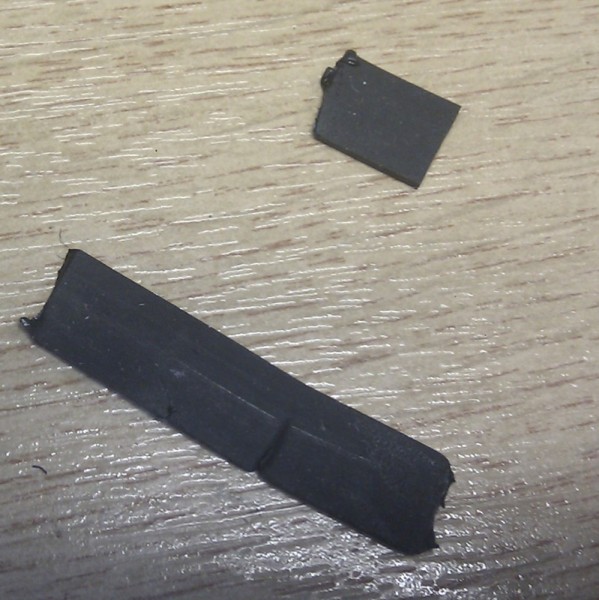

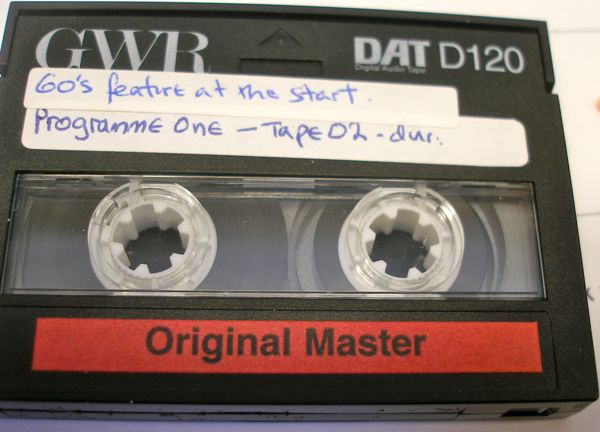

If we take for granted that any kind of data file, whether analogue or digital, will have been altered in its lifetime in some way, either through changes to the signal, file structure or because of poor storage, an important question arises from an archival point of view. What do we do with the quality of the data customers send us to digitise? If the signal of a video tape is fuzzy, should we try to stabilise the image? If there is hiss and other forms of noise on tape, should we reduce it? Should we apply the same conservation values to audio and film as we do to historic buildings, such as ruins, or great works of art? Should we practice minimal intervention, use appropriate materials and methods that aim to be reversible, while ensuring that full documentation of all work undertaken is made, creating a trail of endless metadata as we go along?

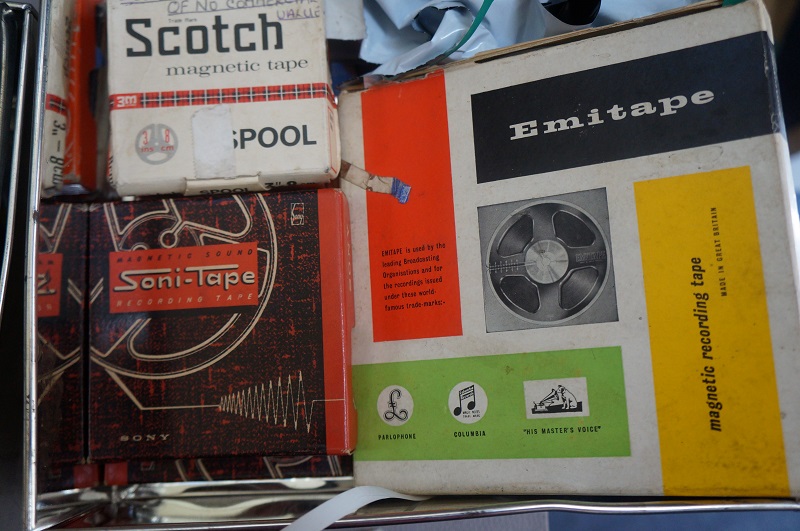

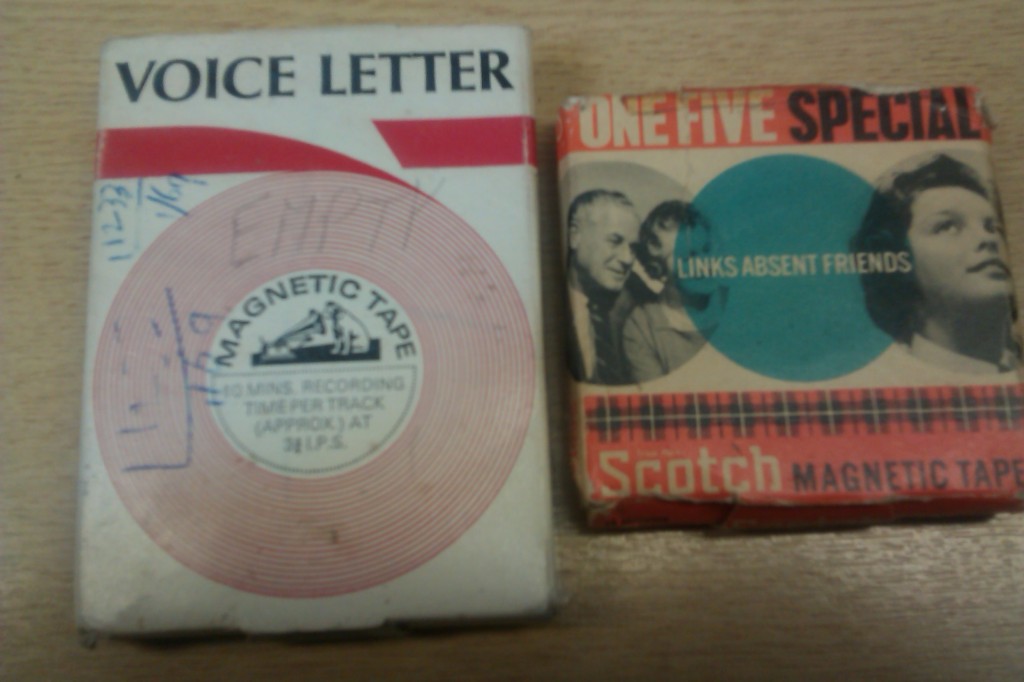

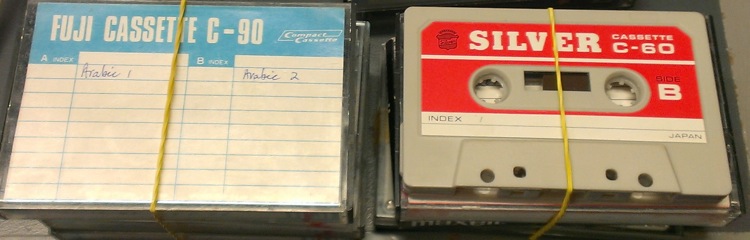

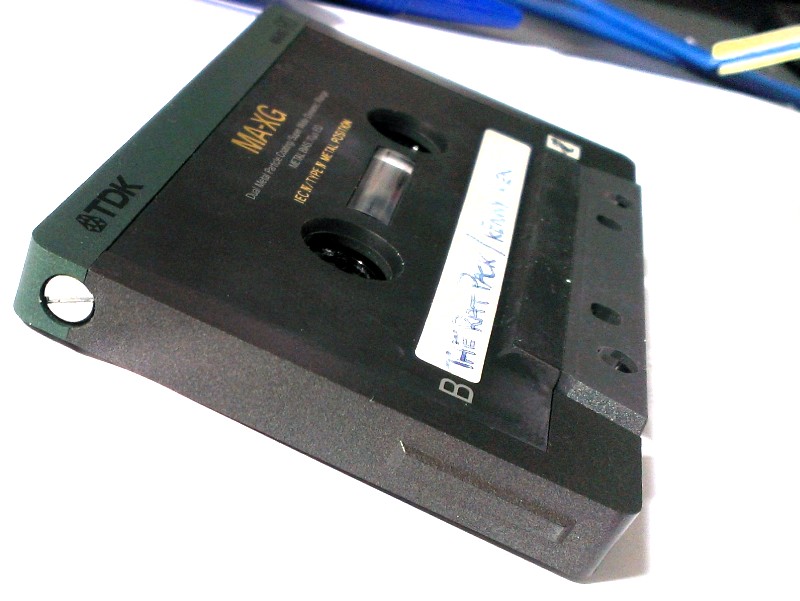

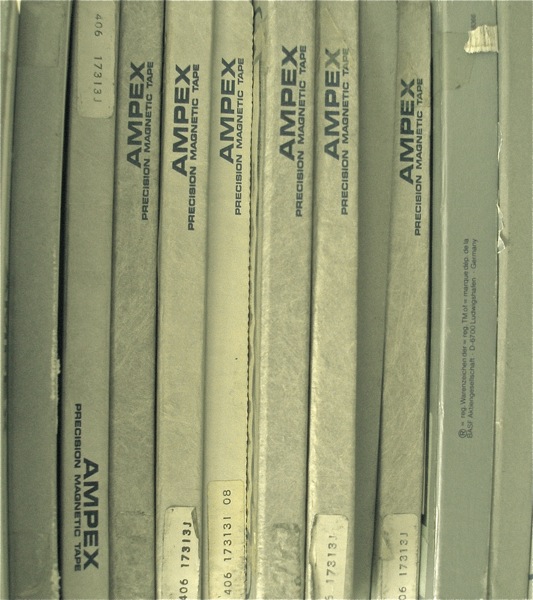

Do we need to preserve the ways magnetic tape, optical media and digital files degrade and deteriorate over time, or are the rules different for media objects that store information which is not necessarily exclusive to them (the same recording can be played back on a vinyl record, a cassette tape, a CD player, an 8 track cartridge or a MP3 file, for example)? Or should we ensure that we can hear and see clearly, and risk altering the original recording so we can watch a digitised VHS on a flat screen HD television, in line with our current expectations of media quality?

Richard Wright suggests it is the data, rather than operating facility, which is the important thing about the digital preservation of audio and audiovisual media.

‘These patterns (for film) and signals (for video and audio) are more like data than like artefacts. The preservation requirement is not to keep the original recording media, but to keep the data, the information, recovered from that media’ (3).

Yet it is not always easy to understand what parts of the data should be discarded, and which parts should kept. Audiovisual and audio data are a production of both form and content, and it is worth taking care over the practices we use to preserve our collections in case we overlook the significance of this point and lose something valuable – culturally, historically and technologically.