As an archival process digitisation offers the promise of a dream: improved accessibility, preservation and storage.

However the digital age is not without its archival headaches. News of the BBC’s plans to abandon their Digital Media Initiative (DMI), which aimed to make the BBC media archive ‘tapeless’, clearly demonstrates this. As reported in The Guardian:

‘DMI has cost £98.4m, and was meant to bring £95.4m of benefits to the organisation by making all the corporation’s raw and edited video footage available to staff for re-editing and output. In 2007, when the project was conceived, making a single TV programme could require 70 individual video-handling processes; DMI was meant to halve that.’

The project’s failure has been explained by its size and ambition. Another telling reason was cited: the software and hardware used to deliver the project was developed for exclusive use by the BBC. In a statement BBC Director Tony Hall referred to the fast development of digital technology, stating that ‘off-the-shelf [editing] tools were now available that could do the same job “that simply didn’t exist five years ago”.’

The fate of the DMI initiative should act as a sobering lesson for institutions, organisations and individuals who have not thought about digitisation as a long, rather than short term, archival solution.

As technology continues to ‘innovate’ at startling rate, it is hard to predict how long the current archival standard for audio and audio-visual will last.

Being an early adopter of technology can be an attractive proposition: you are up to date with the latest ideas, flying the flag for the cutting edge. Yet new technology becomes old fast, and this potentially creates problems for accessing and managing information. The fragility of digital data comes to the fore, and the risk of investing all our archival dreams in exclusive technological formats as the BBC did, becomes far greater.

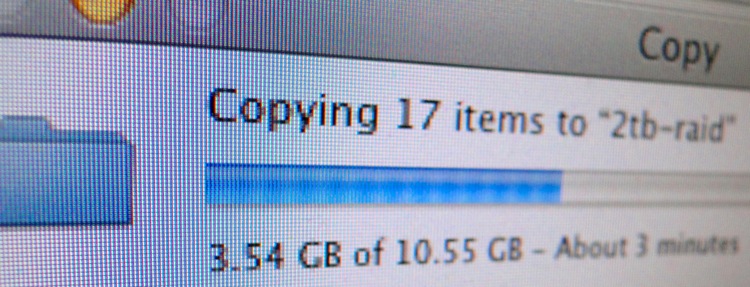

In order for our data to survive we need to appreciate that we are living in what media theorist Jussi Parikka calls an ‘information management society.’ Digitisation has made it patently clear that information is dynamic rather than stored safely in static objects. Migrating tape based archives to digital files is one stage in a series of transitions material can potentially make in its lifetime.

Given the evolution of media and technology in the 20th and 21st centuries, it feels safe to speculate that new technologies will emerge to supplant uncompressed WAV and AIFF files, just as AAC has now become preferred to MP3 as a compressed audio format because it achieves better sound quality at similar bit rates.

Because of this at Greatbear we always migrate analogue and digital magnetic tape at the recommended archival standard, and provide customers with high quality and access copies. Furthermore, we strongly recommend to customers to back up archive quality files in at least three separate locations because it is highly likely data will need to be migrated again in the future.