We have previously written on this blog about the problems that can occur when transferring Digital Audio Tapes (DATs).

According to preliminary findings from the British Library’s important survey of the UK’s sound collections, there are 3353 DAT tapes in the UK’s archives.

While this is by no means a final figure (and does not include the holdings of record companies and DATheads), it does suggest there is a significant amount of audio recorded on this obsolete format which, under certain conditions, is subject to catastrophic signal loss.

The conditions we are referring to is that old foe of magnetic tape: mould.

In contrast with existing research about threats to DAT, which emphasise how the format is threatened by ‘known playback problems that are typically related to mechanical alignment’, the biggest challenges we consistently face with DATs is connected to mould.

It is certainly acknowledged that ‘environmental conditions, especially heat, dust, and humidity, may also affect cassettes.’

Nevertheless, the specific ways mould growth compromise the very possibility of successfully playing back a DAT tape have not yet been fully explored. This in turn shapes the kinds of preservation advice offered about the format.

What follows is an attempt to outline the problem of mould growth on DATs which, even in minimal form, can pretty much guarantee the loss of several seconds of recording.

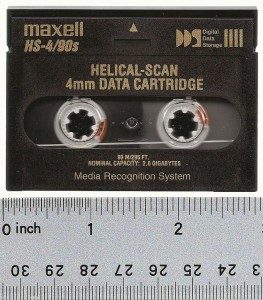

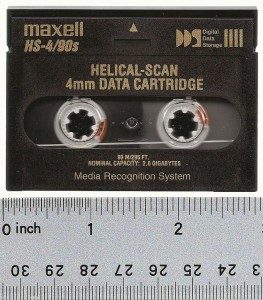

The first problem with DATs is that they are 4mm wide, and very thin in comparison to other forms of magnetic tape.

The size of the tape is compounded by the helical method used in the format, which records the signal as a diagonal stripe across the tape. Because tracks are written onto the tape at an angle, if the tape splits it is not a neat split that can be easily spliced together.

The only way to deal with splits is to wind the tape back on to the tape transport or use leader tape to stick the tape back together at the breaking point.

Either way, you are guaranteed to lose a section of the tape because the helical scan has imprinted the recorded signal at a sharp, diagonal angle. If a DAT tape splits, in other words, it cuts through the diagonal signal, and because it is digital rather than analogue audio, this results in irreversible signal loss.

And why does the tape split? Because of the mould!

If you play back a DAT displaying signs of dormant mould-growth it is pretty much guaranteed to split in a horrible way. The tape therefore needs to be disassembled and wound by hand. This means you can spend a lot of time restoring DATs to a playable condition.

Rewinding by hand is however not 100% fool-proof, and this really highlights the challenges of working with mouldy DAT tape.

Often mould on DATs is visible on the edge of the tape pack because the tape has been so tightly wound it doesn’t spread to the full tape surface.

In most cases with magnetic tape, mould on the edge is good news because it means it has not spread and infected the whole of the tape. Not so with DAT.

Even with tiny bits of mould on the edge of the tape there is enough to stick it to the next bit of tape as it is rewound.

When greater tension is applied in an attempt to release the mould, due to stickiness, the tape rips.

A possible and plausible explanation for DAT tape ripping is that due to the width and thinness of the tape the mould is structurally stronger than the tape itself, making it easier for the mould growth to stick together.

When tape is thicker, for example with a 1/4 ” open reel tape, it is easier to brush off the dormant mould which is why we don’t see the ripping problem with all kinds of tape.

Our experience confirms that brushing off dormant mould is not always possible with DATs which, despite best efforts, can literally peel apart because of sticky mould.

What, then, is to be done to ensure that the 3353 (and counting) DAT tapes in existence remain in a playable condition?

One tangible form of action is to check that your DATs are stored at the appropriate temperature (40–54°F [4.5–12°C]) so that no mould growth develops on the tape pack.

The other thing to do is simple: get your DAT recordings reformatted as soon as possible.

While we want to highlight the often overlooked issue of mould growth on DATs, the problems with machine obsolescence, a lack of tape head hours and mechanical alignment problems remain very real threats to successful transfer of this format.

Our aim at the Greatbear is to continue our research in the area of DAT mould growth and publish it as we learn more.

As ever, we’d love to hear about your experiences of transferring mouldy DATs, so please leave a comment below if you have a story to share.

I would love to know if you have made any progress with this. I have a bunch of Maxell DDS tapes and BASF audio DATs (which appear to have an identical housing to Maxell) which are tightly stuck. Attempting to gently manually separate the tape end from the reel may result in a short section being freed up but it will still break at the next sticky section. I have been able to manually wind other types of DAT past the sticky sections but these Maxell/BASF tapes are proving a real headache.

Hi James,

Yes these can be a nightmare and when the layers are tightly stuck it’s not really feasible to unwind these affected tapes. It’s not clear to us if the worst affected tapes are brand related or type / quantity of mould growth..

With care, IPA and lots of time many tapes can be saved but it’s never ideal and most have been played and ripped prior to the discovery of mould sadly..