Greatbear are delighted to be working with the Potteries Heritage Society to digitise a unique collection of tape recordings made in the 1970s and 80s by radio producer, jazz musician and canals enthusiast Arthur Wood, who died in 2005.

The project, funded by a £51,300 grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), will digitise and make available hundreds of archive recordings that tell the people’s history of the North Staffordshire area. There will be a series of events based on the recordings, culminating in an exhibition in 2018.

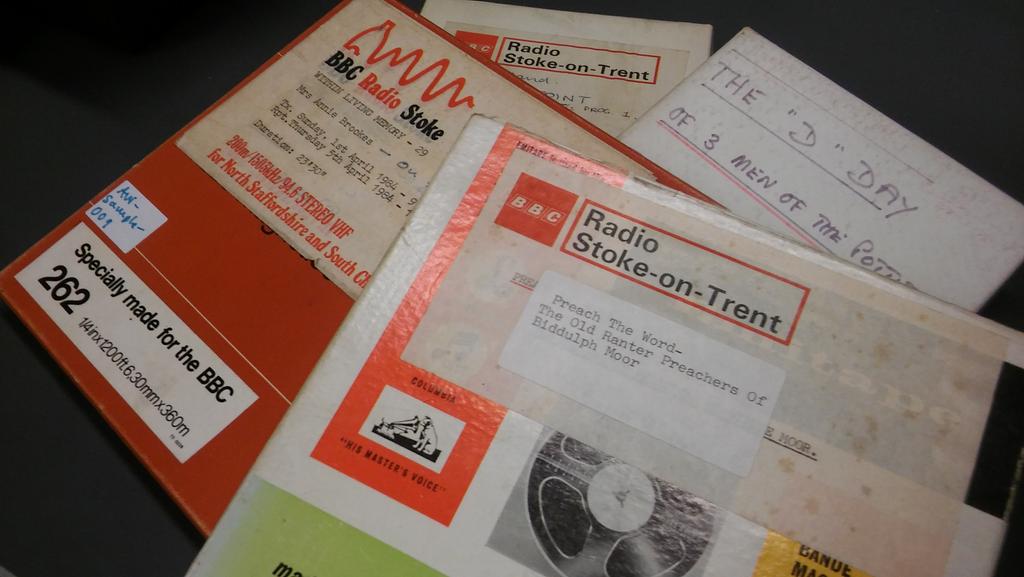

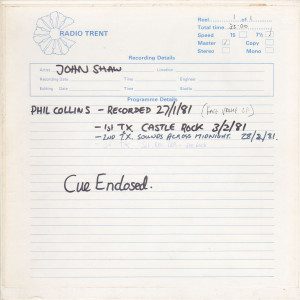

The recordings were originally made for broadcast on BBC Radio Stoke, where Arthur Wood was education producer in the 1970s and 80s. They feature local history, oral history, schools broadcasts, programmes on industrial heritage, canals, railways, dialect, and many other topics of local interest.

There are spontaneous memoirs and voxpop interviews as well as full-blown scripted programmes such as the ‘Ranter Preachers of Biddulph Moor’ and ‘The “D”-Day of 3 Men of the Potteries’ and ‘Millicent: Lady of Compassion’, a programme about 19th century social reformer Millicent, Duchess of Sutherland.

Arthur Wood: Educational Visionary

In an obituary published in The Guardian, David Harding described Wood as ‘a visionary. He believed radio belonged to the audience, and that people could use it to find their own voice and record their history. He taught recording and editing to many of his contributors – miners, canal, steel and rail workers, potters, children, artists, historians and storytellers alike.’

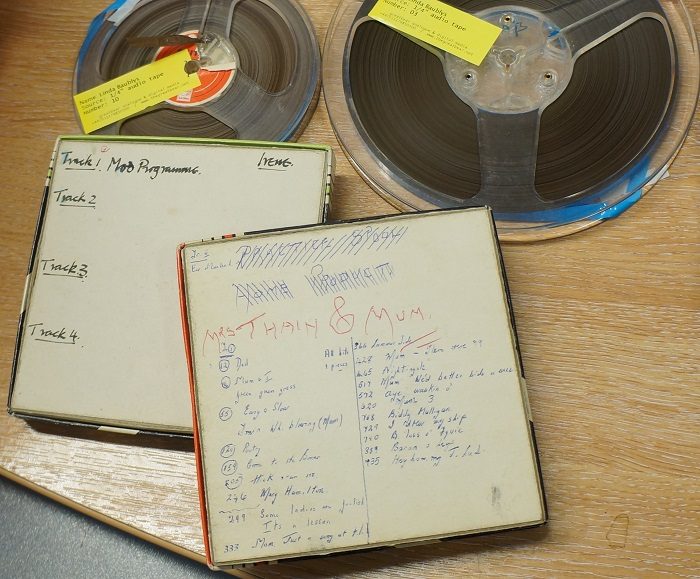

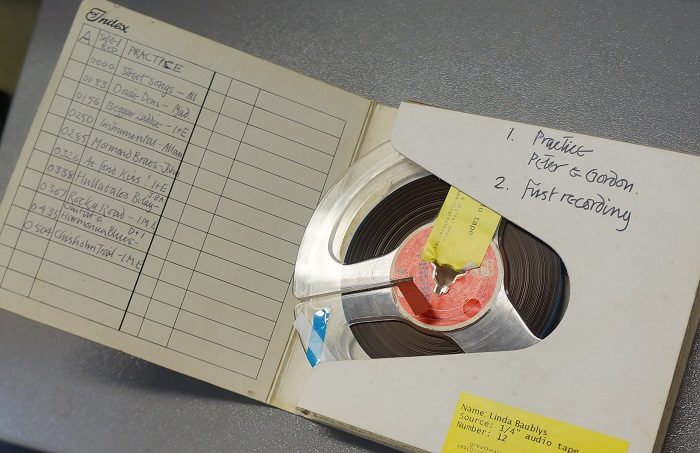

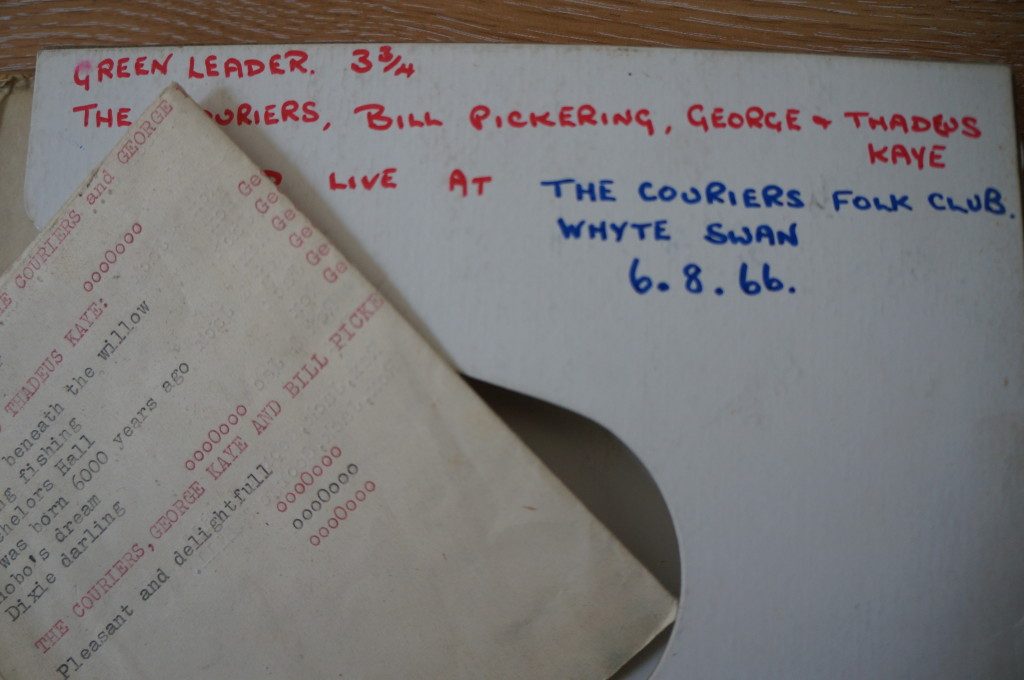

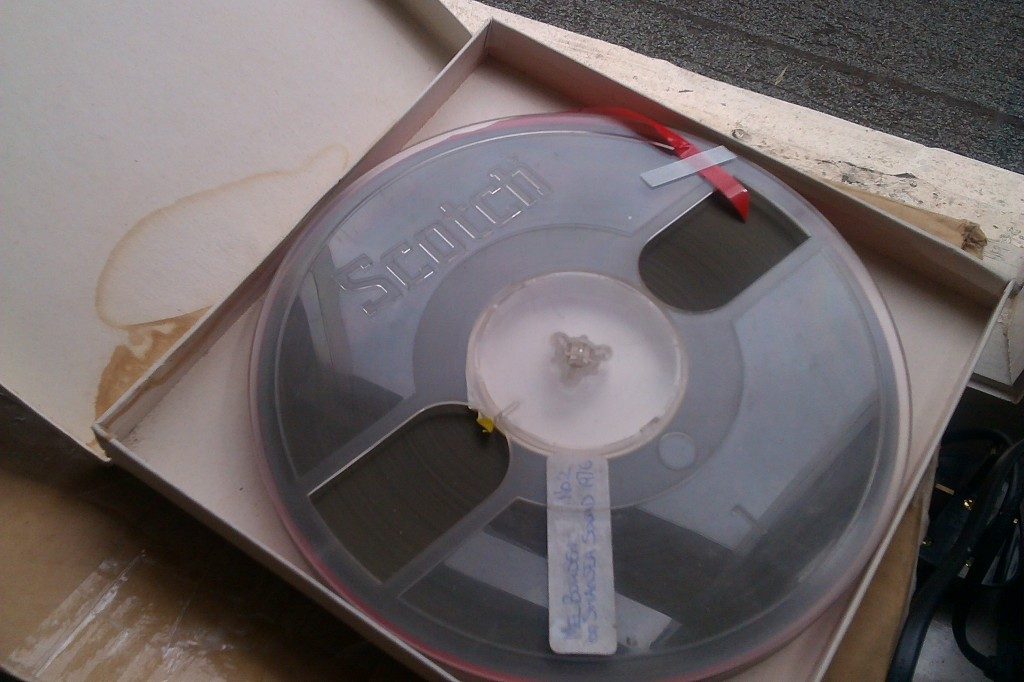

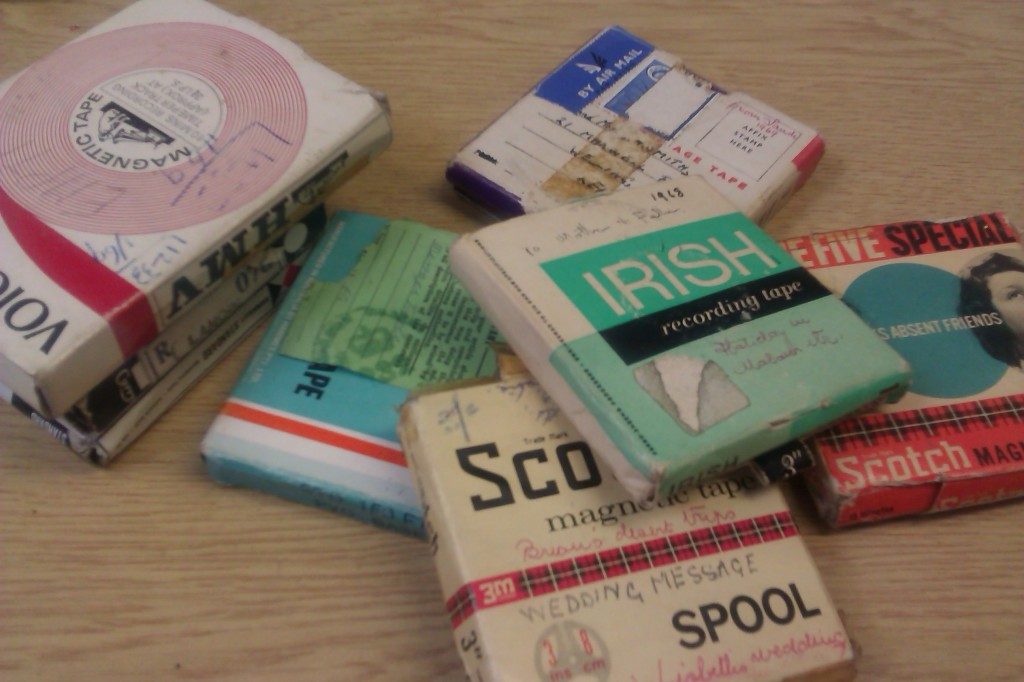

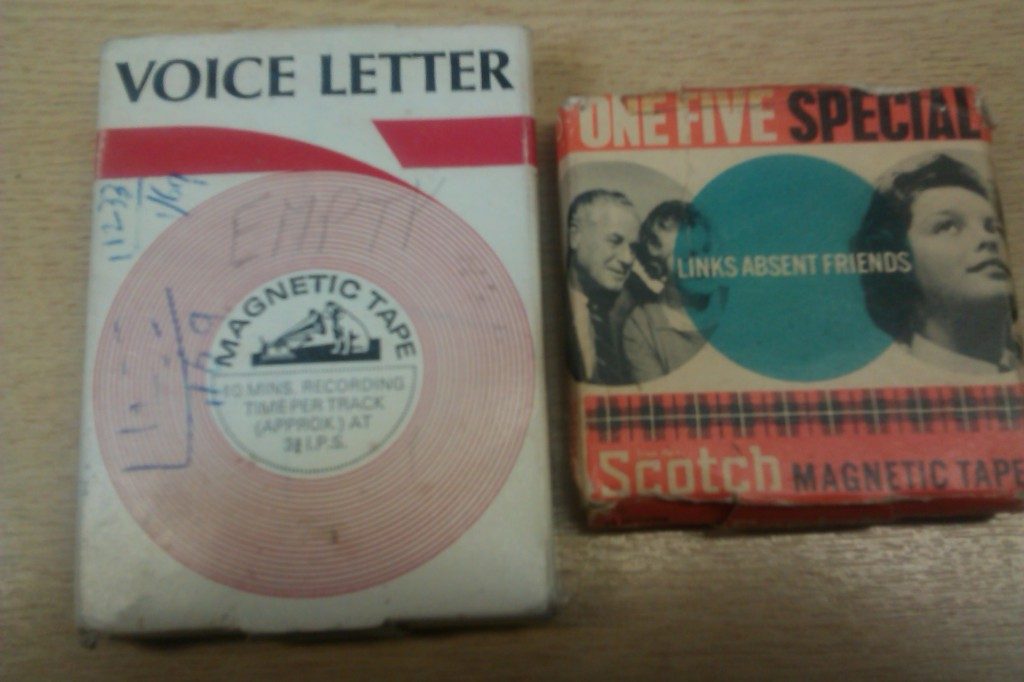

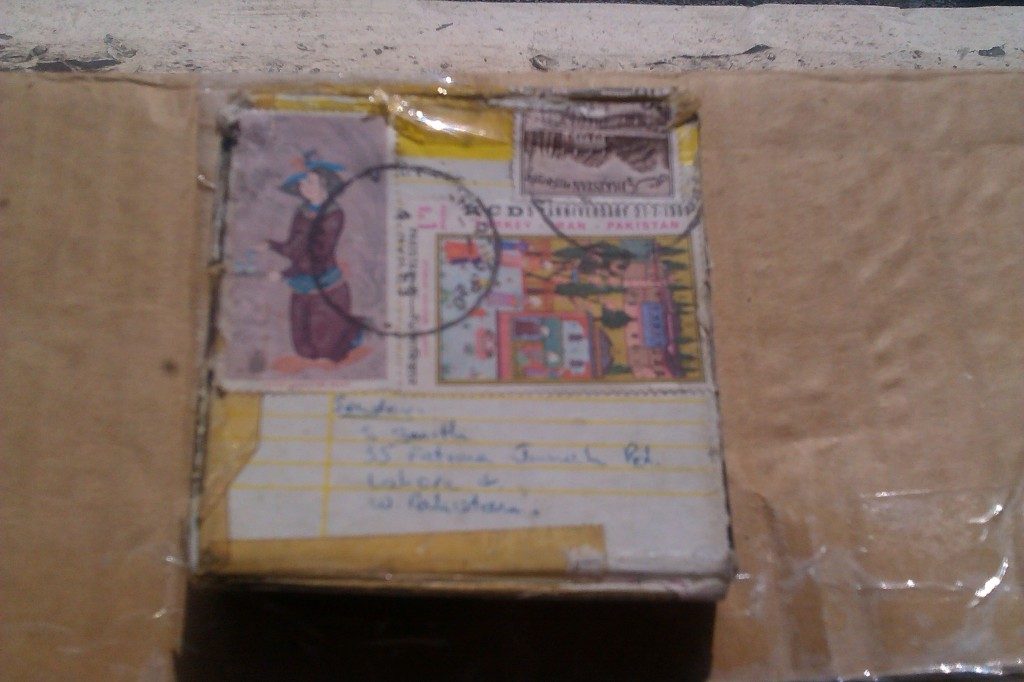

The tapes Greatbear will be digitising reflect what Wood managed to retain from his career at the BBC.

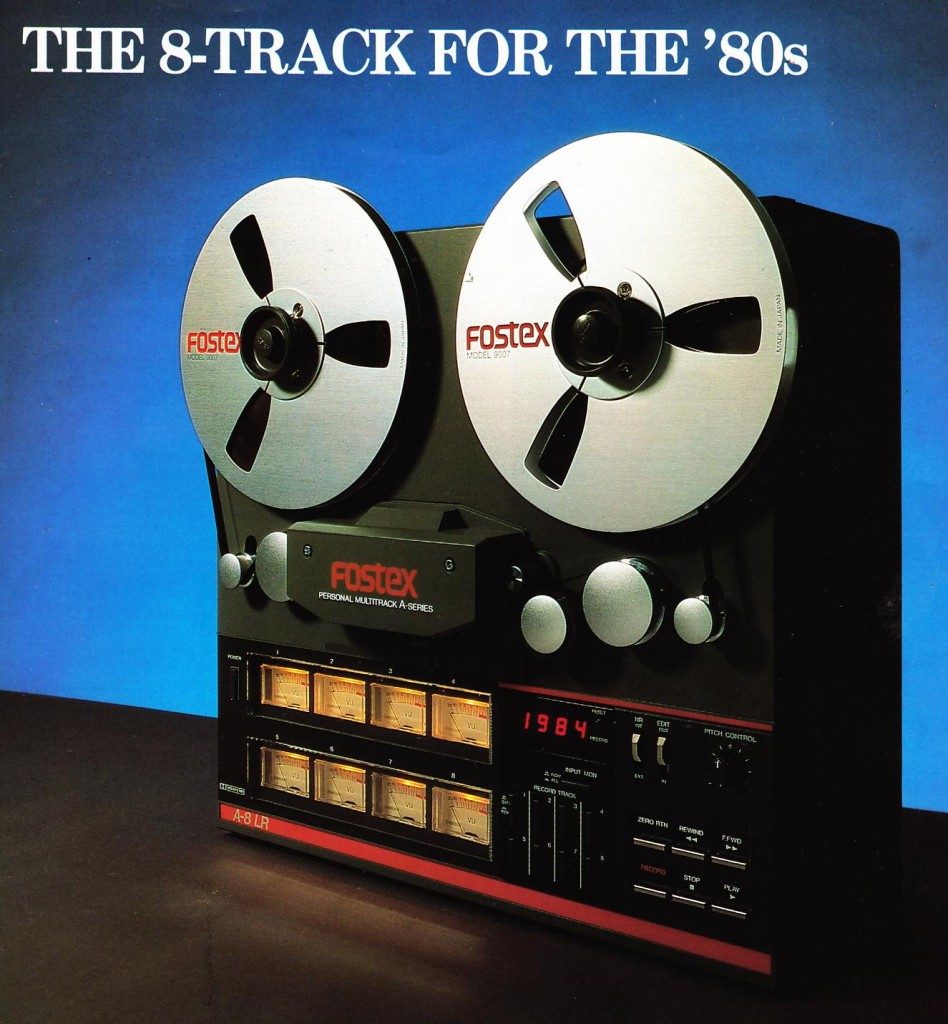

Before BBC Radio Stoke moved premises in 2002, Wood picked up as many tapes as he could and stored them away. His plan was to transfer them to a more future proof format (which at the time was mini disc!) but was sadly unable to do this before he passed away.

‘About 2 years ago’ Arthur’s daughter Jane explains, ‘I thought I’d go and have a look at what we actually had. I was surprised there were quite so many tapes (about 700 in all), and that they weren’t mainly schools programmes, as I had expected.

I listened to a few of them on our old Revox open reel tape machine, and soon realised that a lot of the material should be in the city (and possibly national) archives, where people could hear it, not in a private loft. The rest of the family agreed, so I set about researching how to find funding for it.’

50th anniversary of BBC Local Radio

The Revealing Voices project coincides with an important cultural milestone: the 50th anniversary of BBC local radio. Between 1967 and 1968 the BBC was granted license to set up a number of local radio stations in Durham, Sheffield, Brighton, Leicester, Merseyside, Nottingham, Leeds and Stoke-on-Trent.

Education was central to how the social role of local radio was imagined at the time:

‘Education has been a major preoccupation of BBC Local Radio from the outset. Indeed, in one sense, the entire social purpose of local radio, as conceived by the BBC, may be described as educational. As it is a central concern of every civilised community, so too must any agency serving the aims of such a community treat it as an area of human activity demanding special regard and support. It has been so with us. Every one of our stations has an educationist on its production staff and allocates air-time for local educational purposes’ (Education and BBC Local Radio: A Combined Operation by Hal Bethell, 1972, 3).

Within his role as education producer Wood had a remit to produce education programmes in the broadest sense – for local schools, and also for the general local audience. Arthur ‘was essentially a teacher and an enthusiast, and he sought to share local knowledge and stimulate reflective interest in the local culture mainly by creating engaging programmes with carefully chosen contributors,’ Jane reflected.

Revealing Voices and Connecting Histories

Listening to old recordings of speech, like gazing at old photograph, can be very arresting. Sound recordings often contain an ‘element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me’, akin to Roland Barthes might have called a sonic punctum.

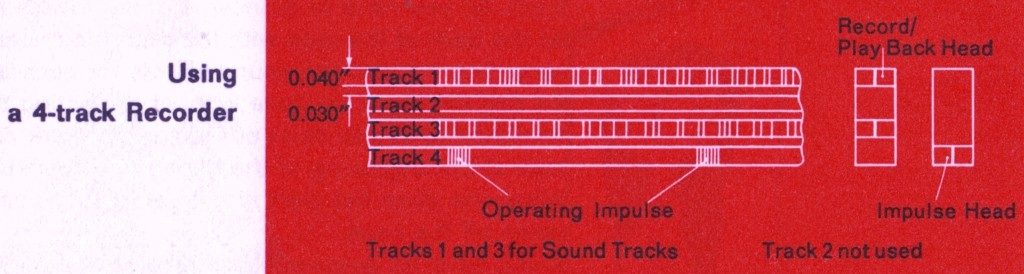

The potency of recorded speech, especially in analogue form, arises from its indexicality—or what we might call ‘presence’. This ‘presence’ is accentuated by sound’s relational qualities, the fact that the person speaking was undeniably there in time, but when played back is heard but also felt here.

When Jane dropped off the tapes in the Greatbear studio she talked of the immediate impact of listening again to her father’s tape collection. The first tape she played back was a recording of a woman born in 1879, recalling, among other things, attending a bonfire to celebrate Queen Victoria’s jubilee.

Hearing the voice gave her a distinct sense of being connected to a woman’s life across three different centuries. This profound and unique experience was made possible by the recordings her father captured in the 1970s, unwinding slowly on magnetic tape.

The Revealing Voices project hope that other people, across north Staffordshire and beyond, will have a similar experiences of recognition and connection when they listen to the transferred tapes. It would be a fitting tribute to Arthur Wood’s life-work, who, Jane reflects, would be ‘glad that a solution has been found to preserve the tapes so that future generations can enjoy them.’

***

If you live in the North Staffordshire area and want to volunteer on the Revealing Voices project please contact Andy Perkin, Project Officer, on andy at revealing-voices dot org dot uk.

Many thanks to Jane Wood for her feedback and support during research for this article.