Introduced by SONY in 1971 U-matic was, according to Jeff Martin, 'the first truly successful videocassette format'.

Philips’ N-1500 video format dominated the domestic video tape market in the 1970s. By 1974 U-matic was widely adopted in industrial and institutional settings. The format also performed a key role in the development of Electronic News Gathering. This was due to its portability, cost effectiveness and rapid integration into programme workflow. Compared with 16mm film U-matic had many strengths.

The design of the U-matic case mimicked a hardback book. Mechanical properties were modelled on the audio cassette's twin spool system.

Like the Philips compact audio cassette developed in the early 1960s, U-matic was a self-contained video playback system. This required minimal technical skill and knowledge to operate.

There was no need to manually lace the video tape through the transport, or even rewind before ejection like SONY's open reel video tape formats, EIAJ 1/2" and 1" Type C. Stopping and starting the tape was immediate, transferring different tapes quick and easy. U-matic ushered in a new era of efficiency and precision in video tape technology.

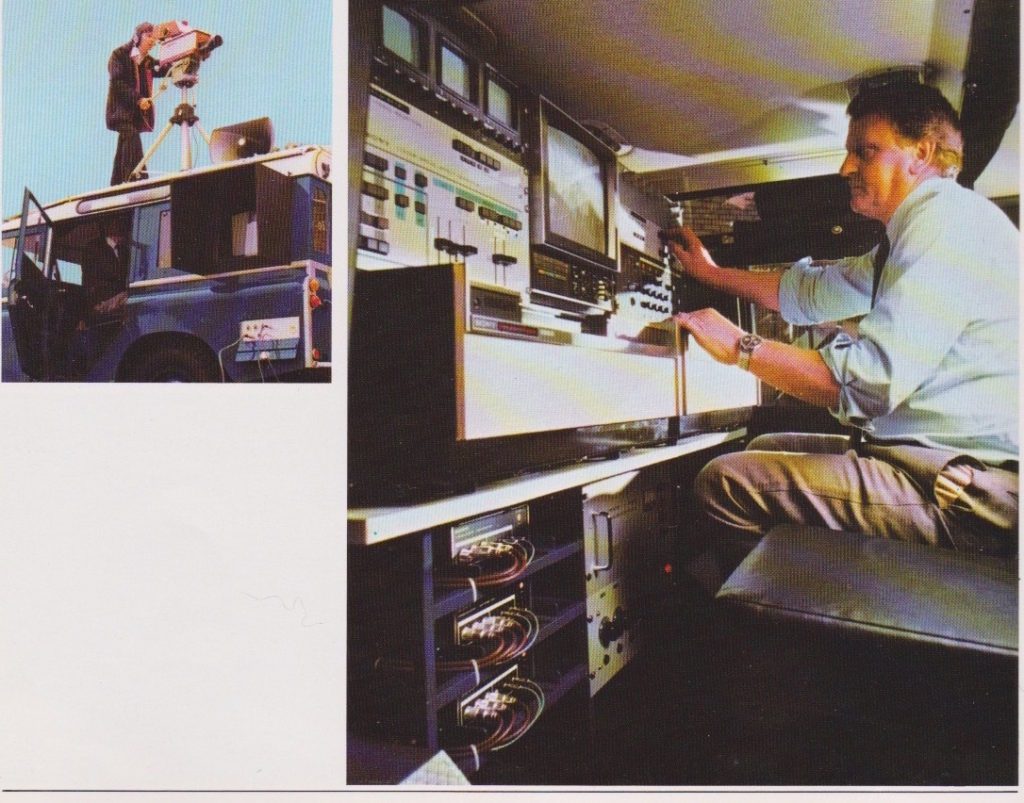

Mobile news-gathering on U-matic video tape

Emphasising technical quality and user-friendliness was key to marketing U-matic video tape.

As SONY's product brochure states, 'it is no use developing a TV system based on highly sophisticated knowledge if it requires equally sophisticated knowledge to be used'.

'The 'ease of operation' is demonstrated in publicity brochures in a series of images. These guide the prospective user through tape machine interface. The human operator, insulated from the complex mechanical principles making the machine tick only needs to know a few things: how to feed content and direct pre-programmed functions such as play, record, fast forward, rewind and stop.

New Applications

Marketing material for audio visual technology often helps the potential buyer imagine possible applications. This is especially true when a technology is new.

For SONY’s U-matic video tape it was the ‘very flexibility of the system’ that was emphasised. The brochure recounts a story of an oil tanker crew stationed in the middle of the Atlantic.

After they watch a football match the oil workers sit back and enjoy a new health and safety video. ‘More inclined to take the information from a television set,’ U-matic is presented as a novel way to combine leisure and work.

Ultimately ‘the obligation for the application of the SONY U-matic videocassette system lies with the user…the equipment literally speaks for itself.’

International Video Networks

Before the internet arrived, SONY believed video tape was the media to connect global businesses.

'Ford, ICI, Hambro Life, IBM, JCB...what do these companies have in common, apart from their obvious success? Each of these companies, together with many more, have accepted and installed a new degree of communications technology, the U-matic videocassette system. They need international communication capability. Training, information, product briefs, engineering techniques, sales plans…all can be communicated clearly, effectively by means of television'.

SONY heralded videotape's capacity to reach 'any part of the world...a world already revolutionised by television.' Video tape distributed messages in 'words and pictures'. It enabled simultaneous transmission and connected people in locations as 'wide as the world's postal networks.' With appropriate equipment interoperability between different regional video standards - PAL, NTSC and SECAM - was possible.

Video was imagined as a powerful virtual presence serving international business communities. It was a practical money-saving device and effective way to foster inter-cultural communication: 'Why bring 50 salesmen from the field into Head Office, losing valuable working time when their briefing could be sent through the post?'

Preserving U-Matic Video Tape

According the Preservation Self-Assessment Program, U-matic video tape ‘should be considered at high preservation risk’ due to media and hardware obsolescence. A lot of material was recorded on the U-matic format, especially in media and news-gathering contexts. In the long term there is likely to be more tape than working machines.

Despite these important concerns, at Greatbear we find U-matic a comparatively resilient format. Part of the reason for this is the ¾” tape width and the presence of guard bands that are part of the U-matic video signal. Guard bands were used on U-matic to prevent interference or ‘cross-talk’ between the recorded tracks.

In early video tape design guard bands were seen as a waste of tape. Slant azimuth technology, a technique which enabled stripes to be recorded next to each other, was integrated into later formats such as Betamax and VHS. As video tape evolved it became a whole lot thinner.

In a preservation context thinner tape can pose problems. If tape surface is damaged and there is limited tape it is harder to read a signal during playback. In the case of digital tape, damage on a smaller surface can result in catastrophic signal loss. Analogue formats such as U-matic, often fare better, regardless of age.

Paradoxically it would seem that the presence of guard bands insulates the recorded signal from total degradation: because there is more tape there is a greater margin of error to transfer the recorded signal.

Like other formats, such as the SONY EIAJ, certain brands of U-matic tape can pose problems. Early SONY, Ampex and Kodak branded tape may need dehydration treatment ('baked') to prevent shedding during playback. If baking is not appropriate, we tend to digitise in multiple passes, allowing us to frequently intervene to clean the video heads of potentially clogging material. If your U-matic tape smells of wax crayons this is a big indication there are issues. The wax crayon smell seems only to affect SONY branded tape.

Concerns about hardware obsolescence should of course be taken seriously. Early 'top loading' U-matic machines are fairly unusable now.

Mechanical and electronic reliability for 'front loading' U-matic machines such as the BVU-950 remains high. The durability of U-matic machines becomes even more impressive when contrasted with newer machines such as the DVC Pro, Digicam and Digibeta. These tend to suffer relatively frequent capacitor failure.

Later digital video tape formats also use surface-mounted custom-integrated circuits. These are harder to repair at component level. Through-hole technology, used in the circuitry of U-matic machines, make it easier to refurbish parts that are no longer working.

Transferring your U-matic Collections

U-matic made video cassette a core part of many industries. Flexible and functional, its popularity endured until the 1990s.

Greatbear has a significant suite of working NTSC/ PAL/ SECAM U-matic machines and spare parts.

Get in touch by email or phone to discuss transferring your collection.

Through-hole technology