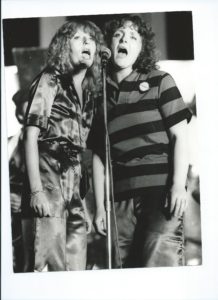

Monstrous Regiment were one of many trailblazing feminist theatre companies active in the 1970s-1990s. They were established as a collective very much built around performers, both (professional) actors such as Mary McCusker and (professional) musicians such as Helen Glavin.

Between 1975-1993 Monstrous Regiment produced a significant number of plays and cabarets. These included Scum: Death, Destruction and Dirty Laundry, Vinegar Tom, Floorshow, Kiss and Kill, Dialogue Between a Prostitute and One of Her Clients, Origin of the Species, My Sister in This House, Medea and many others.

Monstrous Regiment’s plays were not always received positively be feminists. A performance of Time Gentlemen Please (1978), for example, was controversially shut down in Leeds when some audience members stormed the stage. The play was, according to some commentators, seen to promote a ‘glossy, middle-class view of sexual liberation.’ [1]

As with any historical event there are many different accounts of what happened that evening. Mary McCusker and Gillian Hanna have discussed their perspective, as performers, in an interview conducted with Unfinished Histories: Recording the History of Alternative Theatre.

A detailed biography of the company can be also found on the Unfinished Histories website, which has loads more information about Women’s, Black, Gay and Lesbian Theatre companies active at the same time as Monstrous Regiment. Check it out!

An Archival Legacy

Monstrous Regiment still exist on paper, but ceased producing in 1993 after the Arts Council withdrew the company’s revenue funding.

To ensure a legacy for Monstrous Regiment’s work the company archive was deposited in the Women’s Library (then Fawcett Library).

Due to a large cataloguing backlog at the Women’s Library, however, the Monstrous Regiment collection was never made publicly available.

Co-founder Mary McCusker explains her frustration with this situation:

‘We were always keen to create a body of work that would be accessible to future practitioners that the work would not be hidden from history, but alas unknown to us it was not catalogued so available to no one. Script were meant to be performed, some of the unpublished plays have not been available for such a long time. I/we do want the ideas the energy of those times the talent and wonderful creativity to be there after we are gone. That goes for the plays’ readings we did as well as the performances.’

‘I admire writers immensely and even if some plays didn’t get the critical response hoped for I believe all the work deserves a space, somewhere to be discovered anew. I would also hope the idea a group of actors started this and kept going, took control over their work conditions and wanted their beliefs to inform what was written and how they worked with other creative beings would still resonate in the future.’

Monstrous Moves

The decision to relocate is part of a new effort to organise and publicly interpret the Monstrous Regiment archive.

Plans are in place to construct a new archival website that will tell the Monstrous Regiment Story. It will include photographs, fliers, scripts, ephemera and – yes – audiovisual material.

Russell Keat, a semi-retired academic and partner of Mary McCusker, has begun the process of looking through the collection at the V & A, selecting items for digitisation and contacting people who performed with Monstrous Regiment to ask for new material.

Russell has also been exploring McCusker’s personal audio cassette collection for traces of Monstrous Regiment. The fruits of this labour were sent to Great Bear for digitisation.

The recordings we transferred include performances of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and Floorshow, a radio broadcast of Mourning Pictures, a spoken voice audio guide of the play The Colony Comes a Cropper for Visually Challenged Audiences, a tape made by a composer for Mary to rehearse with, songs from Vinegar Tom and Kiss and Kill recorded in a rehearsal studio and a sound tape for Love Story of a Century, comprising piano and rain effects.

The (live) Monstrous Regiment Archive

Making audiovisual documentation was an exceptional rather than everyday activity in the late 1970s and early 1980s. ‘We had a few things filmed; not whole plays but maybe snippets. Music taped. Radio interviews and magazine interviews were one way of spreading the word,’ Mary told us.

As a documentary form, the audiovisual recording exists in tension with the theatrical ideal of live performance: ‘It’s very difficult for a film to capture the experience of live theatre because of course you rehearse and produce the play to be experienced live. BUT naturally if that performance has gone and all you have is a script then any filmed documentation gives the reader/viewer all the visual clues about what a character is feeling when they speak but also the bigger picture about how they feel about what other characters are saying,’ Mary reflected.

Live and later recorded music performed a key role in Monstrous Regiment’s work. Unlike other theatre groups such as the Sadista Sisters, Spare Tyre and Gay Sweatshop, Monstrous Regiment never released an album of the music they performed. The tapes Great Bear have transferred will therefore help future researchers understand the musical dimension of the company’s work in a more nuanced way.

Mary explains that ‘from the very start we wanted live music to be part of the shows we produced and encouraged writers to write not only for the company of actors but also to put music as an integral part of the play; to have it as a theatrical force in a central position, not a scene change background filler.

This was true in all our early work and of course in the two cabarets. I think the songs in Vinegar Tom by Caryl Churchill still provoke much discussion. I know I loved singing them. Later as our musicians moved on and also money got tighter we had musicians like Lindsay Cooper and Joanna MacGregor write and perform scores for plays that were recorded and became used rather as you would in cinema.’

We are hugely grateful to Mary and Russell for taking time to respond to our questions for this article.

We wish them the best of luck for their archive project, and will post links to the new website when it hits the servers.

Notes

[1] Aleks Sierz (2014) In-Yer-Face Theatre: British Drama Today, London: Faber and Faber.