We have been featuring various theories about digital information management on this blog in order to highlight some of the debates involved in this complex and evolving field.

To offer a different perspective to those that we have focused on so far, take a moment to consider the principles of Parsimonious Preservation that has been developed by the National Archives, and in particular advocated by Tim Gollins who is Head of Preservation at the Institution.

In some senses the National Archives seem to be bucking the trend of panic, hysteria and (sometimes) confusion that can be found in other literature relating to digital information management. The advice given in the report, ‘Putting Parsimonious Preservation into Practice‘, is very much advocating a hands-off, rather than hands-on approach, which many other institutions, including the British Library, recommend.

The principle that digital information requires continual interference and management during its life cycle is rejected wholesale by the principles of parsimonious preservation, which instead argues that minimal intervention is preferable because this entails ‘minimal alteration, which brings the benefits of maximum integrity and authenticity’ of the digital data object.

As detailed in our previous posts, cycles of coding and encoding pose a very real threat to digital data. This is because it can change the structure of the files, and risk in the long run compromising the quality of the data object.

Minimal intervention in practice seems here like a good idea – if you leave something alone in a safe place, rather than continually move it from pillar to post, it is less likely to suffer from everyday wear and tear. With digital data however, the problem of obsolescence is the main factor that prevents a hands-off approach. This too is downplayed by the National Archives report, which suggests that obsolescence is something that, although undeniably a threat to digital information, it is not as a big a worry as it is often presented.

Gollins uses over ten years of experience at the National Archives, as well as the research conducted by David Rosenthal, to offer a different approach to obsolescence that takes note of the ‘common formats’ that have been used worldwide (such as PDF, .xls and .doc). The report therefore concludes ‘that without any action from even a national institution the data in these formats will be accessible for another 10 years at least.’

10 years may seem like a short period of time, but this is the timescale cited as practical and realistic for the management of digital data. Gollins writes:

‘While the overall aim may be (or in our case must be) for ―permanent preservation […] the best we can do in our (or any) generation is to take a stewardship role. This role focuses on ensuring the survival of material for the next generation – in the digital context the next generation of systems. We should also remember that in the digital context the next generation may only be 5 to10 years away!’

It is worth mentioning here that the Parsimonious Preservation report only includes references to file extensions that relate to image files, rather than sound or moving images, so it would be a mistake to assume that the principle of minimal intervention can be equally applied to these kinds of digital data objects. Furthermore, .doc files used in Microsoft Office are not always consistent over time – have you ever tried to open a word file from 1998 on an Office package from 2008? You might have a few problems….this is not to say that Gollins doesn’t know his stuff, he clearly must do to be Head of Preservation at the National Archives! It is just this ‘hands-off, don’t worry about it’ approach seems odd in relation to the other literature about digital information management available from reputable sources like The British Library and the Digital Preservation Coalition. Perhaps there is a middle ground to be struck between active intervention and leaving things alone, but it isn’t suggested here!

For Gollins, ‘the failure to capture digital material is the biggest single risk to its preservation,’ far greater than obsolescence. He goes on to state that ‘this is so much a matter of common sense that it can be overlooked; we can only preserve and process what is captured!’ Another issue here is the quality of the capture – it is far easier to preserve good quality files if they are captured at appropriate bit rates and resolution. In other words, there is no point making low resolution copies because they are less likely to survive the rapid successions of digital generations. As Gollins writes in a different article exploring the same theme, ‘some will argue that there is little point in preservation without access; I would argue that there is little point in access without preservation.’

This has been bit of a whirlwind tour through a very interesting and thought provoking report that explains how a large memory institution has put into practice a very different kind of digital preservation strategy. As Gollins concludes:

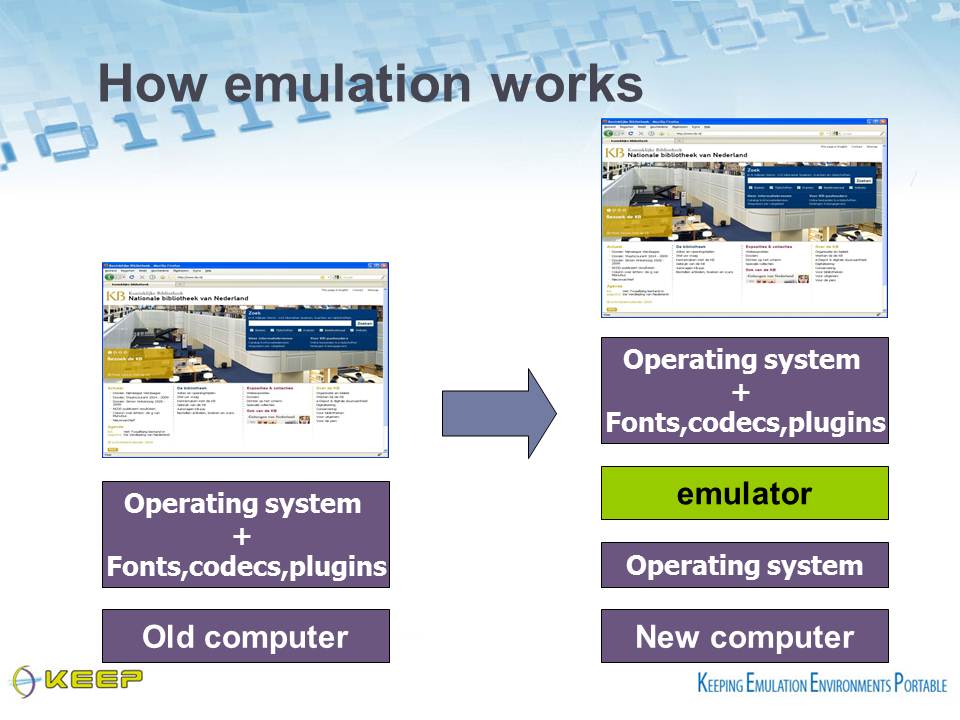

‘In all of the above discussion readers familiar with digital preservation literature will perhaps be surprised not to see any mention or discussion of “Migration” vs. “Emulation” or indeed of ―“Significant Properties”. This is perhaps one of the greatest benefits we have derived from adopting our parsimonious approach – no such capability is needed! We do not expect that any data we have or will receive in the foreseeable future (5 to 10 years) will require either action during the life of the system we are building.’

Whether or not such an approach is naïve, neglectful or very wise, only time will tell.

I (that is the author of this article), wrote an email to the National Archives to see if they could clarify some of the points I raise in this article.

Alex Green responded and has kindly agreed for me to reproduce his answers here. He wanted me to qualify that ‘we are just starting to research approaches to the preservation of digital audio visual material as we receive records of this type. This means that our response reflects only our current views and these may change as we continue our research.’

I wrote:

‘I am a researcher working for a company that digitises magnetic tape, so I do a fair amount of reading of policy reports relating to this area, but was struck by how your recommendations, and development of a digital archive system it proposes, flies in the face of much of the recommendations/ debates that currently surround the issue of digital information management.

My main question was: do you think the principle of non-intervention for the digital data object applies to audio & audio-visual files, as much as it does to documents such as .doc, .pdf etc – what we might call ‘image files’, as your report didn’t seem to be talking about these kinds of digital data objects.’

He wrote:

‘The issue of the long term preservation of digital audio and video content is certainly more complex and problematic than with standard office document formats or still images. Though it is essential that the current and future prospects of these codec/container combinations are continually evaluated on a case by case basis, I believe that the fundamental concept of Parsimonious Preservation remains valid.

Archives are generally restricted by tight budgets and low on resources and so have to take a pragmatic approach to their collections. If AV digital-file material is in a stable form, – i.e. the codecs and container formats are still current and the audio-visual stream essence fully accessible, then it is acceptable that files that meet this criteria are stored in current form. When access to the essence becomes endangered by format redundancy etc then timely action clearly must be taken in order to ensure continued access; generally by migration to a then current and stable format. The timescales involved will obviously depend upon the many aspects and pressures that can affect the prospects of any particular format.’

I wrote:

‘I also felt that there may be a problem with accepting the appearance of common files, as a .doc file saved on a MS Office suite from 1998, may not be the same as one from 2006 – and may not necessarily open – despite having the same file extension. How do you account for these different generational versions, including pdfs? e.g., adobe reader 1.1 and 8.6 are different from each other, and not necessarily compatible. I think such examples pose a problem to the principles of non-intervention, do they not?’

He wrote:

‘Correct and appropriate identification is of course integral to the correct preservation of digital content. The National Archives DROID tool is designed to identify the file by a specific file format signature, specific bit patterns held within the file and its header and defined in that format’s published specifications are used to positively identify that file not just by format but also by format version. Therefore we do capture these details and they are retained in our preservation metadata.

However, it is important to note that identification of file type does not imply structural validity of the file and therefore doesn’t necessarily always mean that you can open the bitstream. In other words is the file genuinely what it purports to be? This is where a suitable validator for the file (if available) comes into play. For example, a JP2 file can be produced from a tiff carrying a specific embedded colourspace, which will then be generated by some encoders with extended JPX parameters, so it is not a valid JP2 file. This may cause current viewers to crash but what are the future implications of this? Will the file be accessible in future generations of decoders?

The point is not that Parsimonious Preservation is the complete answer, but a guiding principle of doing no more than is strictly necessary in the short to medium term as such actions can inadvertently cause preservation to fail in the future through unknown and untended consequences.’

Thanks again to Alex for letting me reproduce this response here!

Do you have any examples of Office .DOC files from 1998 that no longer open? The ones I can find are working fine for me.