In archiving, the simple truth is formats matter. If you want the best quality recording, that not only sounds good but has a strong chance of surviving over time, it needs to be recorded on an appropriate format.

Most of us, however, do not have specialised knowledge of recording technologies and use what is immediately available. Often we record things within limited budgets, and need to make the most of our resources. We are keen to document what’s happening in front of us, rather than create something that will necessarily be accessible many years from now.

At the Great Bear we often receive people’s personal archives on a variety of magnetic tape. Not all of these tapes, although certainly made to ensure memories were recorded, were done on the best quality formats.

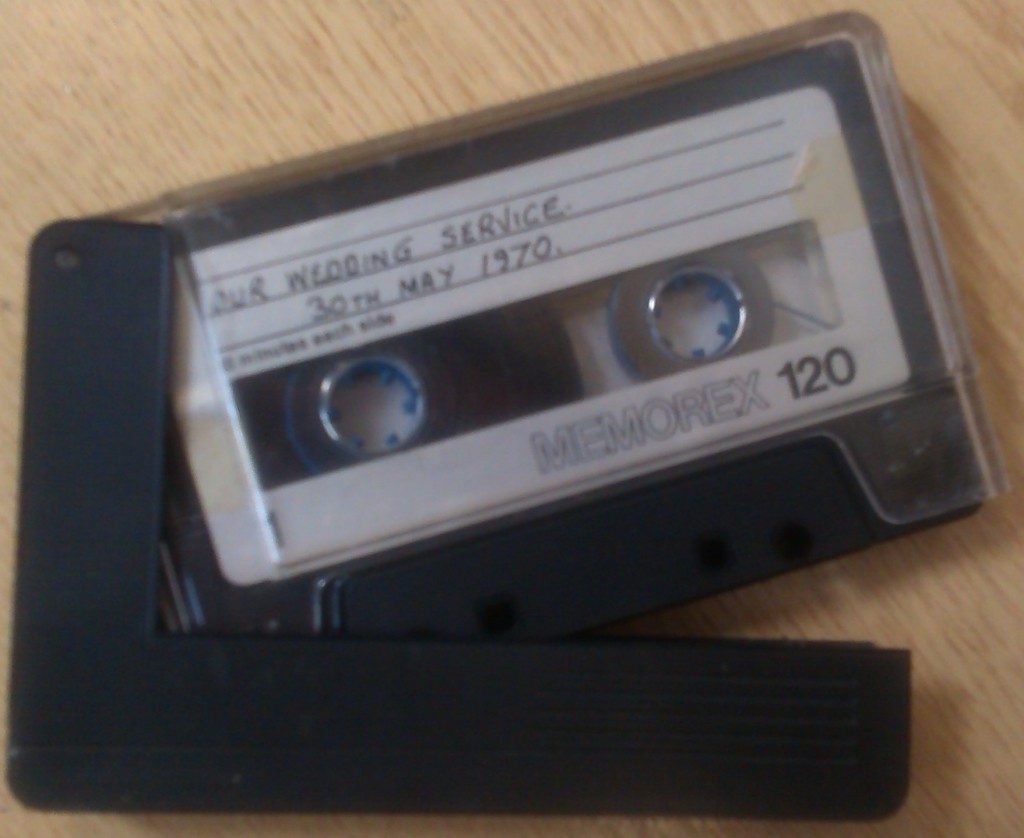

Recently we migrated a recording of a wedding service from 1970 made on C-120 audio cassette.

C60 and C90 tapes are probably familiar to most readers of this blog, but the C-120 was never widely adopted by markets or manufacturers because of its lesser recording quality. The C-120 tape records for an hour each side, and uses thinner tape than its C90 and C60 counterparts. This means the tape is more fragile, and is less likely to produce optimum recordings. Thinner tapes is also more likely to suffer from ‘print-through‘ echo.

As the Nakamichi 680 tape manual, which is pretty much consulted as the bible on all matters tape in the Great Bear studio, insists:

‘Choosing a high quality recording tape is extremely important. A sophisticated cassette deck, like the 680, cannot be expected to deliver superior performance with inferior tapes. The numerous brands and types of blank cassettes on the market vary not only in the consistency of the tape coating, but in the degree of mechanical precision as well. The performance of an otherwise excellent tape is often marred by a poor housing, which can result in skewing and other unsteady tape travel conditions.’

The manual goes on to stress ‘Nakamichi does not recommend the use of C-120 or ferrichrome cassettes under any circumstances.’ Strong words indeed!

It is usually possible to playback most of the tape we receive, but a far greater risk is taken when recordings are made on fragile or low quality formats. The question that has to be thought through when making recordings is: what are you making them for? If they are meant to be a long term record of events, careful consideration of the quality of the recording format used needs to be made to ensure they have the greatest chance of survival.

Such wisdom seems easy to grasp in retrospect, but what about contemporary personal archives that are increasingly ‘born digital’?

A digital equivalent of the C-120 tape would be the MP3 format. While MP3 files are easier to store, duplicate and move across digital locations, they offer substantially less quality than larger, uncompressed audio files, such as WAVs or AIFFs. The current recommended archival standard for recording digital audio is 24 bit/ 48 kHz, so if you are making new recordings, or migrating analogue tapes to digital formats, it is a good idea to ensure they are sampled at this rate

In a recent article called ‘3 Ways to Change the World for Personal Archiving’ on the Library of Congress’ Digital Preservation blog, Bill LeFurgy wrote:

‘in the midst of an amazing revolution in computer technology, there is a near total lack of systems designed with digital preservation in mind. Instead, we have technology seemingly designed to work against digital preservation. The biggest single issue is that we are encouraged to scatter content so broadly among so many different and changing services that it practically guarantees loss. We need programs to automatically capture, organize and keep our content securely under our control.’

The issue of format quality also comes to the fore with the type of everyday records we make of our digital lives. The images and video footage we take on smart phones, for example, are often low resolution, and most people enjoy the flexibility of compressed audio files. In ten years time will the records of our digital lives look pixelated and poor quality, despite the ubiquity of high tech capture devices used to record and share them? Of course, these are all speculations, and as time goes on new technologies may emerge that focus on digital restoration, as well as preservation.

Ultimately, across analogue and digital technologies the archival principles are the same: use the best quality formats and it is far more likely you will make recordings that people many years from now can access.