Metadata is data about data. Maybe that sounds pretty boring, but archivists love it, and it is really important for digitisation work.

As mentioned in the previous post that focused on the British Library’s digital preservation strategies, as well as many other features on this blog, it is fairly easy to change a digital file without knowing because you can’t see the changes. Sometimes changing a file is reversible (as in non-destructive editing) but sometimes it is not (destructive editing). What is important to realise is changing a digital file irrevocably, or applying lossy instead of lossless compression, will affect the integrity and authenticity of the data.

What is perhaps worse in the professional archive sector than changing the structure of the data, is not making a record of it in the metadata.

Metadata is a way to record all the journeys a data object has gone through in its lifetime. It can be used to highlight preservation concerns if, for example, a file has undergone several cycles of coding and decoding that potentially make it vulnerable to degradation.

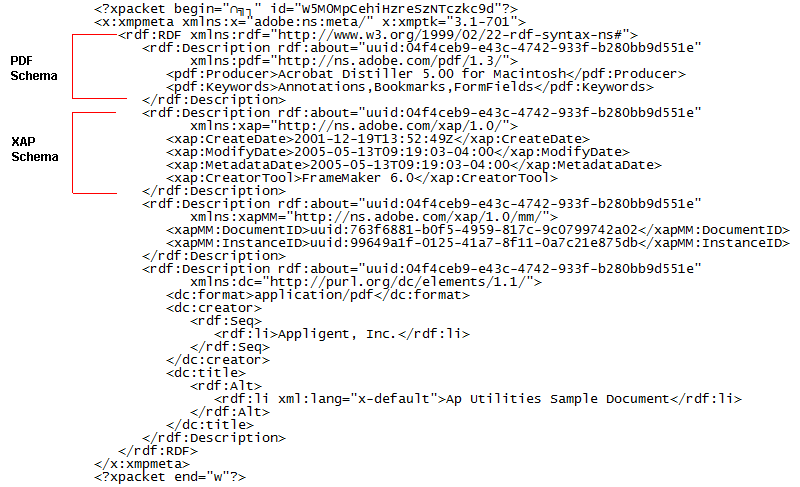

Metadata can in fact be split into three kinds, as Ian Ireland writes in this article:

‘technical data (info on resolution, image size, file format, version, size), structural metadata (describes how digital objects are put together such as a structure of files in different folders) and descriptive (info on title, subject, description and covering dates) with each type providing important information about the digital object.’

As the previous blog entry detailed, digital preservation is a dynamic, constantly changing sector. Furthermore, digital data requires far greater intervention to manage collections than physical objects and even analogue media. In such a context data objects undergo rapid changes as they adapt to the technical systems they are opened by and moved between. This would produce, one would speculate, a large stream of metadata.

What is most revealing about metadata surrounding digital objects, is they create a trail of information not only about the objects themselves. They also document our changing relationship to, and knowledge about, digital preservation. Metadata can help tell the story about how a digital object is transformed as different technical systems are adopted and then left behind. The marks of those changes are carried in the data object’s file structure, and the metadata that further elaborate those changes.

Like those who preserve physical heritage collections, a practice of minimal intervention is the ideal for maintaining both the integrity and authenticity of digital collections. But mistakes are made, and attempts to ‘clean up’ or otherwise clarify digital data do happen, so when they do, it is important to record those changes because they help guide how we look after archives in the long term.