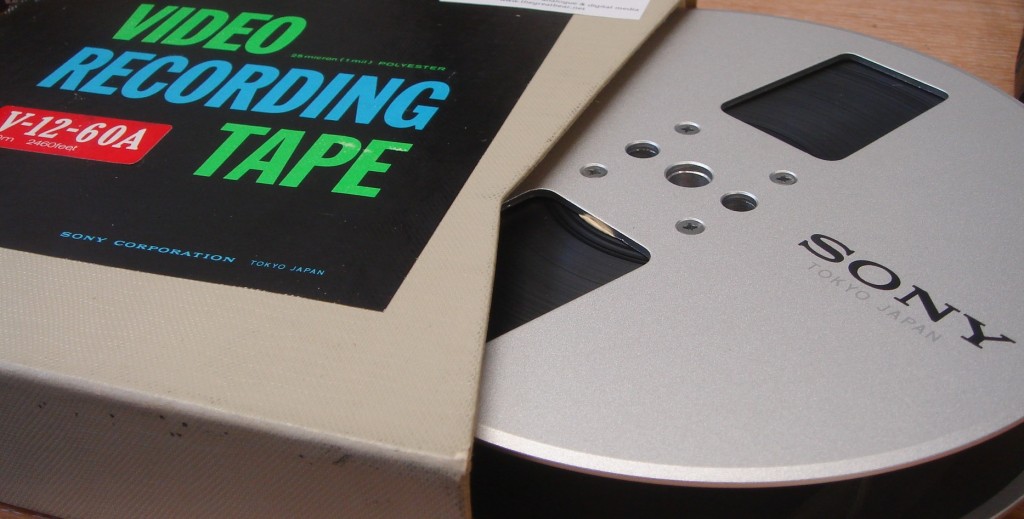

There are an astonishing amount of online resources relating to the preservation and re-formatting of magnetic tape collections.

Whether you need help identifying and assessing your collection, getting to grips with the latest video codec saga or trying to uncover esoteric technical information relating to particular formats, the internet turns up trumps 95% of the time.

Marvel at the people who put together the U-Matic web resource, for example, which has been online since 1999, a comprehensive outline of the different models in the U-Matic ‘family.’ The site also hosts ‘chat pages’ relating to Betamax, Betacam, U-Matic and V2000, which are still very much active, with archives dating back to 1999. For video tape nerds willing to trawl the depths of these forums, nuggets of machine maintenance wisdom await you.

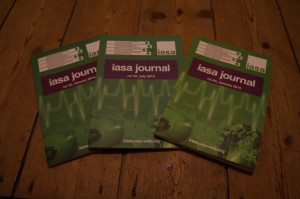

International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives

Sometimes you need to turn to rigorous, peer-reviewed research in order to learn from AV archive specialists.

Fortunately such material exists, and a good amount of it is collected and published by the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives (IASA).

‘Established in 1969 in Amsterdam to function as a medium for international co-operation between archives that preserve recorded sound and audiovisual documents’, IASA holds expertise relating to the many different and specialist issues attached to the care of AV archives.

Comprised of several committees dealing with issues such as standards and best practices; National Archive policies; Broadcast archives; Technical Issues; Research Archives; Training and Education, IASA reflects the diverse communities of practice involved in this professional field.

As well as hosting a yearly international conference (check out this post on The Signal for a review of the 2014 meeting), IASA publish a bi-annual journal and many in-depth specialist reports.

Their Guidelines on the Production and Preservation of Digital Audio Objects (2nd edition, 2009), written by the IASA Technical Committee, is available as a web resource, and provides advice on key issues such as small scale approaches to digital storage systems, metadata and signal extraction from original carriers, to name a few.

Most of the key IASA publications are accessible to members only, and therefore remain behind a paywall. It is definitely worth taking the plunge though, because there are comparably few specialist resources relating to AV archives written with an interdisciplinary—and international—audience in mind.

Examples of issues covered in member-only publications include Selection in Sound Archives, Decay of Polymers, Deterioration of Polymers and Ethical Principles for Sound and Audiovisual Archives.

The latest publication from the IASA Technical Committee, Handling and Storage of Audio and Video Carriers (2014) or TC05, provides detailed outlines of types of recording carriers, physical and chemical stability, environmental factors and ‘passive preservation,’ storage facilities and disaster planning.

The report comes with this important caveat:

‘TC 05 is not a catalogue of mere Dos and Don’ts. Optimal preservation measures are always a compromise between many, often conflicting parameters, superimposed by the individual situation of a collection in terms of climatic conditions, the available premises, personnel, and the financial situation. No meaningful advice can be given for all possible situations. TC 05 explains the principal problems and provides a basis for the archivist to take a responsible decision in accordance with a specific situation […] A general “Code of Practice” […] would hardly fit the diversity of structures, contents, tasks, environmental and financial circumstances of collections’ (6).

Member benefits

Being an IASA member gives Greatbear access to research and practitioner communities that enable us to understand, and respond to, the different needs of our customers.

Typically we work with a range of people such as individuals whose collections have complex preservation needs, large institutions, small-to-medium sized archives or those working in the broadcast industry.

Our main concern is reformatting the tapes you send us, and delivering high quality digital files that are appropriate for your plans to manage and re-use the data in the future.

If you have a collection that needs to be reformatted to digital files, do contact us to discuss how we can help.