On a recent trip to one of Britain’s most significant community archives, I was lucky enough to watch a rare piece of digitised video footage from the late 1970s.

As the footage played it raised many questions in my mind: who shot it originally? What format was it originally created on? How was it edited? How was it distributed? What was the ‘life’ of the artefact after it ceased to actively circulate within communities of interest/ use? How and who digitised it?

As someone familiar with the grain of video images, I could make an educated guess about the format. I also made other assumptions about the video. I imagined there was a limited amount of tape available to capture the live events, for example, because a number of still images were used to sustain the rolling audio footage. This was unlikely to be an aesthetic decision given that the aim of the video was to document a historic event. I could be wrong about this, of course.

When I asked the archivist the questions flitting through my mind she had no answers. She knew who the donor of the digital copy was, but nothing about the file’s significant properties. Nor was this important information included in the artefact’s record.

This struck me as a hugely significant problem with the status of digitised material – and especially perhaps video – in mixed-content archives where the specificities of AV content are not accounted for.

Due to the haphazard and hand-to-mouth way mixed-content archives have acquired digital items, it seems more than likely this situation is the rule rather than the exception: acquired bit by bit (no pun intended), maintaining access is often privileged over preserving the context and context of the digitised video artefact.

As a researcher I was able to access the video footage, and this of course is better than nothing.

Yet I was viewing the item in an ahistoric black hole. It was profoundly decontextualised; an artefact extracted to its most barest of essences.

Standard instabilities

This is not in any way a criticism of the archive in question. In fact, this situation is wholly understandable given that digital video are examples of ‘media formats that exist in crisis.’

Video digitisation remains a complex and unstable area of digital preservation. It is, as we have written elsewhere on this blog, the final frontier of audiovisual archiving. This seems particularly true within the UK context where there is currently no systematic plan to digitise video collections, unlike film and audio.

The challenge with digital video preservation remains the bewildering number of potential codec/ wrapper combinations that can be used to preserve video content.

There are signs, however, that file-format stabilities are emerging. The No Time to Wait: Standardizing FFV1 & Matroska for Preservation symposium (Berlin, July 2016) brought together software developers and archivists who want to make the shared dream of an open source lossless video standard, fit for archival purpose, a reality.

It seems like the very best minds are working together to solve this problem, so Greatbear are quietly optimistic that a workable, open source standard for video digital preservation is in reach in the not too distant future.

Metadata

Yet as my experience in the archive makes clear, the challenge of video digitisation is not about file format alone.

There is a pressing need to think very carefully about the kind of metadata and other contextual material that need to be preserved within and alongside the digitised file.

Due to limited funding and dwindling technical capacity, there is likely to be only one opportunity to transfer material currently recorded on magnetic tape. This means that in 2016 there really can be no dress rehearsal for your video digitisation plans.

As Joshua Ranger strongly emphasises:

‘Digitization is preservation…For audiovisual materials. And this bears repeating over and over because the anti-digitization voice is much stronger and generally doesn’t include any nuance in regards to media type because the assumption is towards paper. When we speak about digitization for audio and video, we now are not speaking about simple online access. We are speaking about the continued viability, about the persistence and the existence of the media content.’

What information will future generations need to understand the digitised archive materials we produce?

An important point to reckon with here is that not all media are the same. The affordances of particular technologies, within specific historical contexts, have enabled new forms of community and communicative practice to emerge. Media are also disruptive (if not deterministic) – they influence how we see the world and what we can do.

On this blog, for example, Peter Sachs Collopy discussed how porta-pak technology enabled video artists and activists in the late 1960s/ early 1970s to document and re-play events quickly.

Such use of video is also evident in the 1975 documentary Les prostituées de Lyon parlent (The prostitutes of Lyon speak).

Les prostituées documents a wave of church occupations by feminist activists in France.

The film demonstrates how women used emergent videotape technology to transmit footage recorded within the church onto TV screens positioned outside. Here videotape technology, and in particular its capacity to broadcast uni-directional messages, was used to protect and project the integrity of the group’s political statements. Video, in this sense, was an important tool that enabled the women – many of whom were prostitutes and therefore without a voice in French society – to ‘speak’.

Peter’s interview and Les prostituées de Lyon parlent are specific examples of how AV formats are concretely embedded within a social-historical and technical context. The signal captured – when reduced to bit stream alone – is simply not an adequate archival source. Without sufficient context too much historical substance is shed.

In this respect I disagree with Ranger’s claim that ‘all that really may be needed moving ahead [for videotape digitisation] is a note in the record for the new digital preservation master that documents the source.’ To really preserve the material, the metadata record needs to be rich enough for a future researcher to understand how a format was used, and what it enabled users to do.

‘Rich enough’ will always be down to subjective judgement, but such judgements can be usefully informed by understanding what makes AV archive material unique, especially within the context of mixed-content archives.

Moving Forward

So, to think about this practically. How could the archive item I discuss at the beginning of the article be contextualised in a way that was useful to me, as a researcher?

At the most basic level the description would need to include:

- The format it was recorded on, including details of tape stock and machine used to record material

- When it was digitised

- Who digitised it (an individual, an institution)

In an ideal world the metadata would include:

- Images of the original artefact – particularly important if digital version is now the only remaining copy

- Storage history (of original and copy)

- Accompanying information (e.g., production sheets, distribution history – anything that can illuminate the ‘life’ of artefact, how it was used)

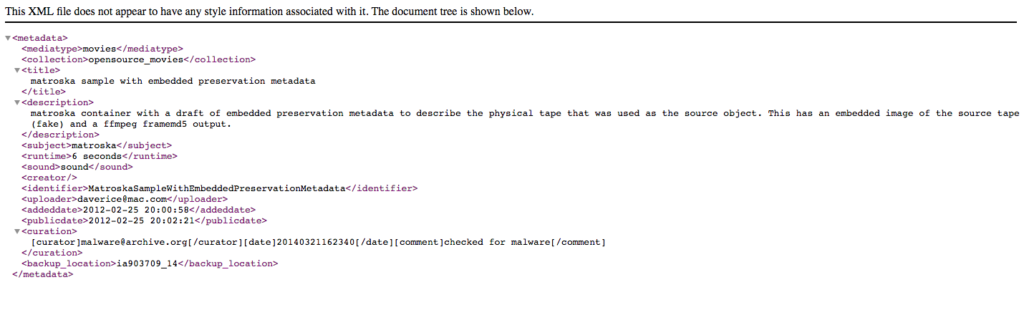

This information could be embedded in the container file or be stored in associated metadata records.

In every other area of archival life, preserving the context of item is deemed important. The difference with AV material is that the context of use is often complex, and in the case of video, is always changing.

As stressed earlier: in 2016 and beyond you will probably only get one chance to transfer collections stored on magnetic tape, so it is important to integrate rich descriptions as part of the transfer.

Capturing the content alone is not sufficient to preserve the integrity of the video artefact. Creating a richer metadata record will take more planning and time, but it will definitely be worth it, especially if we try to imagine how future researchers might want to view and understand the material.