The scale of digitisation jobs we do at Greatbear often varies. We are asked by our customers to reformat single items to large quantities of tape and everything else inbetween.

Reformatting magnetic tape-based media always takes time and care.

Transfers have to be done in real time; if you want a good quality recording there is no way to reformat tape-based media quickly.

Some jobs are so big, however, that you need to find ways of speeding up the process. This is known as a parallel ingest – when you transfer a batch of tapes at the same time.

Realistically, parallel ingest is not possible with all formats.

An obvious issue is machine scarcity. To playback tapes at the same time you need multiple playback machines that are in fairly good condition. This becomes difficult with rarer formats like early digital video tape, such as D1 or D2, where you are extremely lucky if you have two machines working at any given time.

Audio Cassettes

Audio cassette tapes are one of few formats where archival standard parallel ingest is possible if tapes are in good condition and the equipment is working well.

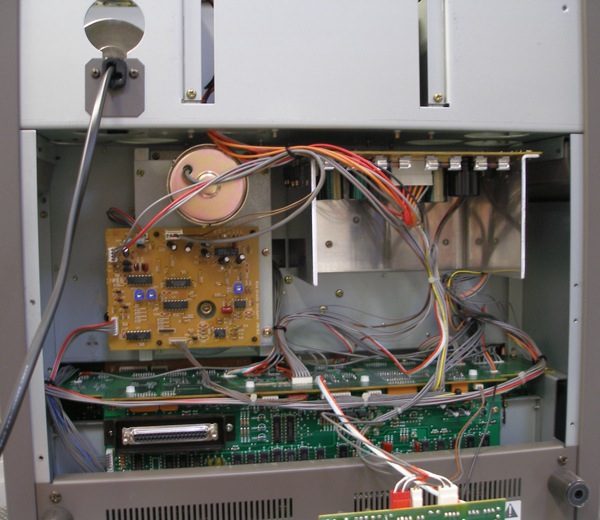

Great Bear Parallel Ingest Stack

We were recently approached by Jim Shields of the Zion, Sovereign Grace Baptists Church in Glasgow to do a large scale transfer of 5000 audio cassettes and over 100 open reels.

Jim explains that these ‘tapes represent the ministry of Pastor Jack Glass, who was the founder of Zion, Sovereign Grace Baptists Church, located at Calder St.Polmadie, Glasgow. The church was founded in 1965. All early recordings are on reel but the audio tapes represent his ministry dating from the beginning of 1977 through to the end of 2003. The Pastor passed away on the 24th Feb 2004 [you can read obituaries here and here]. It is estimated there are in the region of 5,000 ministry tapes varying in length from 60 mins to 120 mins, with many of the sermons being across 2 tapes as the Pastor’s messages tended to be in the region of 90 minutes plus.’

Sermons were recorded using ‘semi domestic to professional cassette decks. From late Sept 1990 a TEAC X-2000 reel recorder was used [to make master copies] on 10 inch reels then transposed onto various length cassettes [when ordered by people]’ chief recordist Mike Hawkins explains.

Although audio cassettes were a common consumer format it is still possible to get high quality digital transfers from them, even when transferred en masse. Recordings of speech, particularly of male voices which have a lower frequency range, are easier to manage.

Hugh Robjohns, writing in 1997 for the audio technology magazine Sound on Sound, explains that lower frequency recordings are mechanically more compatible with the chemical composition of magnetic tape: ‘high-frequency signals tend to be retained by the top surface of the magnetic layer, whilst lower-frequency components tend to be recorded throughout its full depth. This has a bearing on the requirements of the recording heads and the longevity of recordings.'[1]

Preparation

In order to manage a large scale job we had to increase our operational capacity.

We acquired several professional quality cassette machines with auto reverse functions, such as the Marantz PMD 502 and the Tascam 322.

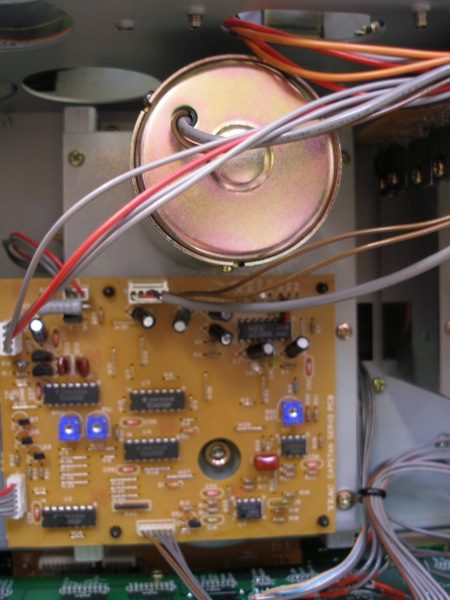

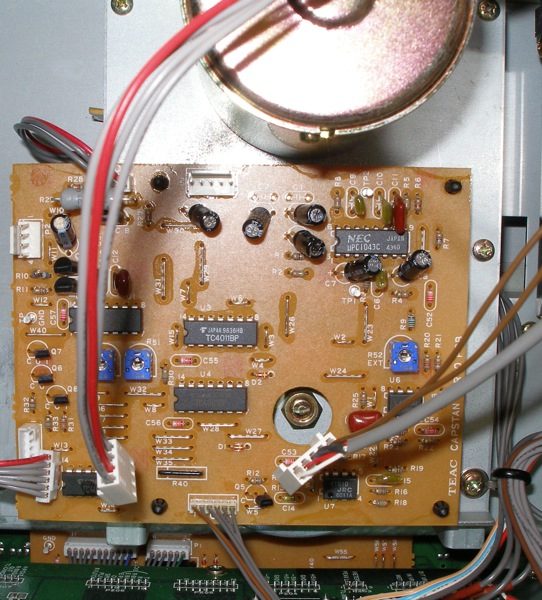

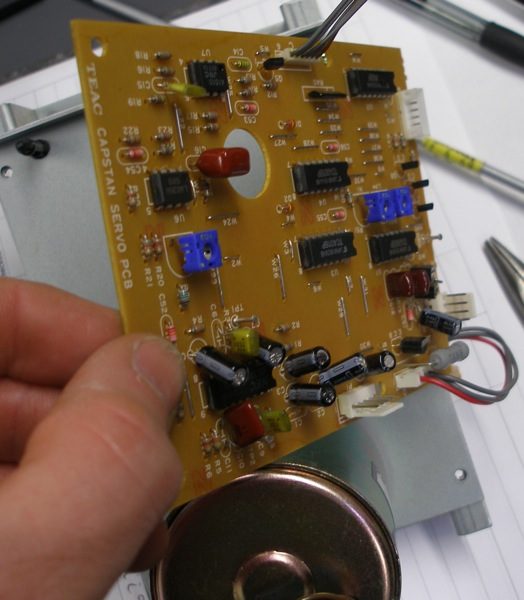

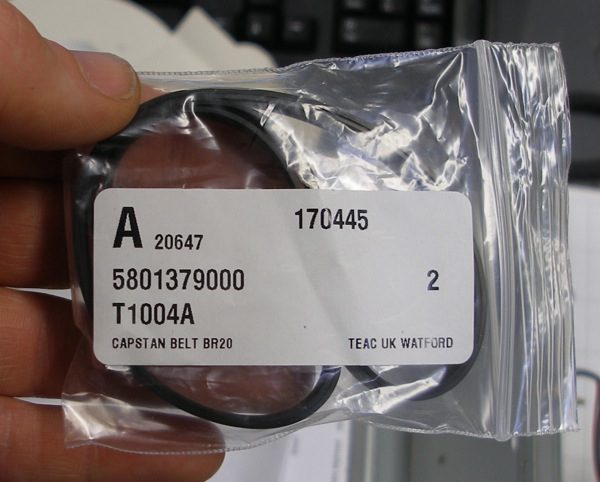

Although these were the high end audio cassette recorders of their time, we found that important components, such as the tape transport which is ‘critical to the performance of the entire tape recorder'[2], were in poor shape across all the models. Pitch and timing errors, or wow (low speed variations) and flutter (high speed variations), were frequently evident during test playbacks.

Because of irregular machine specifications, a lot of time was spent going through all the tape decks ensuring they were working in a standardised manner.

In some cases it was necessary to rebuild the tape transport using spares or even buying a new tape transport. Both of these restoration methods will become increasingly difficult in years to come as parts become more and more scarce.

Assessing the options

There are certainly good reasons to do parallel ingests if you have a large collection of tapes. Nevertheless it is important to go into large scale transfers with your eyes open.

There is no quick fix and there are only so many hours in the working day to do the transfers, even if you do have eight tapes playing back simultaneously.

To assess the viability of a large scale parallel ingest you may want to consider the following issues: condition of tapes, how they were originally recorded and the material stored on them.

It may well be that parts of your collection can be reformatted via parallel ingest, but other elements need to be selected for more specialist attention.

As ever we can help with discussing the options so do contact us if you want some specific advice.

Notes

[1] The gendered implications of this statement are briefly worth reflecting on here. Robjohns suggests that voices which command the higher frequencies, i.e., female or feminine voices, are apparently incompatible with the chemical composition of magnetic tape. If higher frequencies are retained by the top layer of magnetic tape only, but do not penetrate its full depth, does this make high frequencies more vulnerable in a preservation context because they never were never substantially captured in the first place? What does this say about how technical conditions, whose design has often been authored by people with low frequency voices (i.e., men), privilege the transmission of particular frequencies over others, at least in terms of ‘depth’?

[2] Hugh Robjohns ‘Analogue Tape Recorders: Exploration’ Sound on Sound, May 1997. Available: http://www.soundonsound.com/sos/1997_articles/may97/analysinganalogue.html.

*** Many thanks to Jim Shields, Martyn Glass and Mike Hawkins for sharing their tape stories***