It might be a familiar story to some people. At one point, say the late 1970s, you were in your early 20s and the main songwriter in a post-punk/ new wave band. You tried really hard to get it off the ground: moved to London, met the right people, played several memorable gigs.

You worked with talented artists, some went on to become successful pop stars.

You were also pretty organised. You managed to record your music in a professional recording studio. But the band faltered due to commercial reasons, personality differences etc, etc.

The dream of a pop music career faded but, undeterred, you started a new solo project. You built your sound on cutting edge technology – the reliable pulses of the drum machine.

Modest success followed, including an album release on one of the early 1980s many DIY record labels. You secured high profile support slots for big acts, such as the Thompson Twins, and wowed spectators with an idiosyncratic musical style.

Yet it was not possible to make music your profession, and you drifted away from the industry.

The only evidence you ever existed, in a musical sense, was that a friend—Robyn Hitchcock of the Soft Boys—covered your songs from time to time.

Re-discovery

30 years later you start scratching around the internet and realise that the album you made in 1980 is now highly collectable. It’s selling for silly prices on ebay. It seems that all this time you’ve had a cult following on college radio in the US.

This kick starts a self-archiving project, powered by the publishing power of youtube. You start to upload your back catalogue without a shred of wishfulness over what might have been. What the hell, at least people can hear the music now.

Soon you get an email from Manufactured Recordings, an independent record label in Brooklyn who specialise in re-issues. They love you! And want to release and listen to absolutely everything you have done.

Then, in 2017, the entire back catalogue of The Containers, your band that never quite made it, will be released. The compilation carries the title Self-Contained.

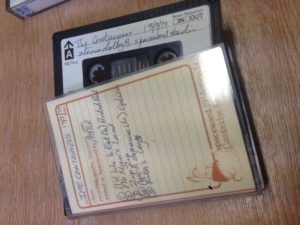

The material on this album, like so many re-issues available today, were expertly transferred in the Greatbear studio!

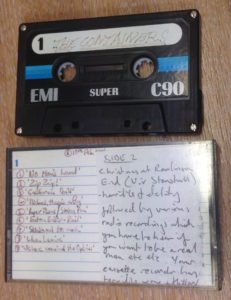

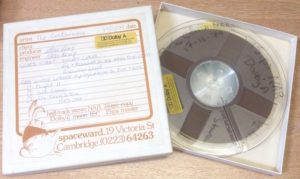

Finally the world will be able to hear The Containers’ ‘lost album’, that was recorded in 1979 at Spaceward studio, Cambridge.

Spaceward had a reputation for making ‘no-nonsense, quality recordings that successfully captured the essence of the late seventies style of music.’ Artists such as The Raincoats, Scritti Politti, Gary Numan, The Mekons and many others laid down tracks there. At the helm was Mike Kemp, a supportive and inventive engineer who, James remembered, checked the final mix through a transistor radio whose battery had half expired.

What can we expect to hear when the The Containers’ music is finally released into the world? The band, James explained, combined ‘literate songwriting with the energy of the period.’ ‘We weren’t afraid of using more than three chords. We wanted to write great songs, with witty, biting lyrics.’

Re-issuing music culture

The contemporary ‘re-issue market’ is built upon the desirability of ‘some mislaid masterwork, tugged from obscurity, relieved of dust, and repackaged for rediscovery.’

While ‘re-issue’ culture can be traced back to the mid-twentieth century, widespread digitisation has clearly fuelled the eruption of pop music’s archival imaginary in the 21st century. Different categories of recorded sound – including more messy or unfinished works – can be decoded as ‘valuable’ or ‘interesting’.

James’ new label, Manufactured Records, for example, wanted to publish demos, rough bedroom recordings and other works in progress as well as the The Containers’ studio recordings.

Such recordings, James believes, have novelty value because they provide unique insight into ‘mindset of the artist’ when they were writing a piece of music. They may also capture the acoustic textures of everyday sound environments, a factor which sets them apart from the flat polished surfaces of (less authentic) studio recordings.

Uncontained

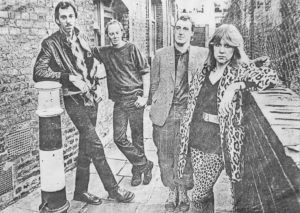

The Containers (l-r) James A Smith – gtr. vocals, Adrian ‘Hots’ Foster – bass gtr, Alan Bearham – drums, Josephine Buchan – vocals

The timely recognition of the Containers and the Beach Bullies should warm the hearts of anyone who has felt that their music careers happened within a bell jar.

It is clear, from speaking with James, the immense pleasure and excitement he feels in being rediscovered after many years.

What’s more, the future appears bright for his musical endeavours: to celebrate the release of the album next year The Containers will go on tour again, featuring the original drummer and bassist.

The moment has come for this ‘music out of time’, that was only played live on a few occasions in the early 1980s, to live again.

***

Many thanks to James A Smith for sharing his memories with us.