How did the Museum of Magnetic Sound Recording get started, what kind of equipment does it collect and what do they think the future holds for magnetic tape?

Many thanks to Martin for taking time to respond to our questions. If you want to support the Museum of Magnetic Sound Recording’s aim to establish a permanent storage facility you can make a donation here.

Enjoy!

GB: When and how did the Museum of Magnetic Sound Recording get started?

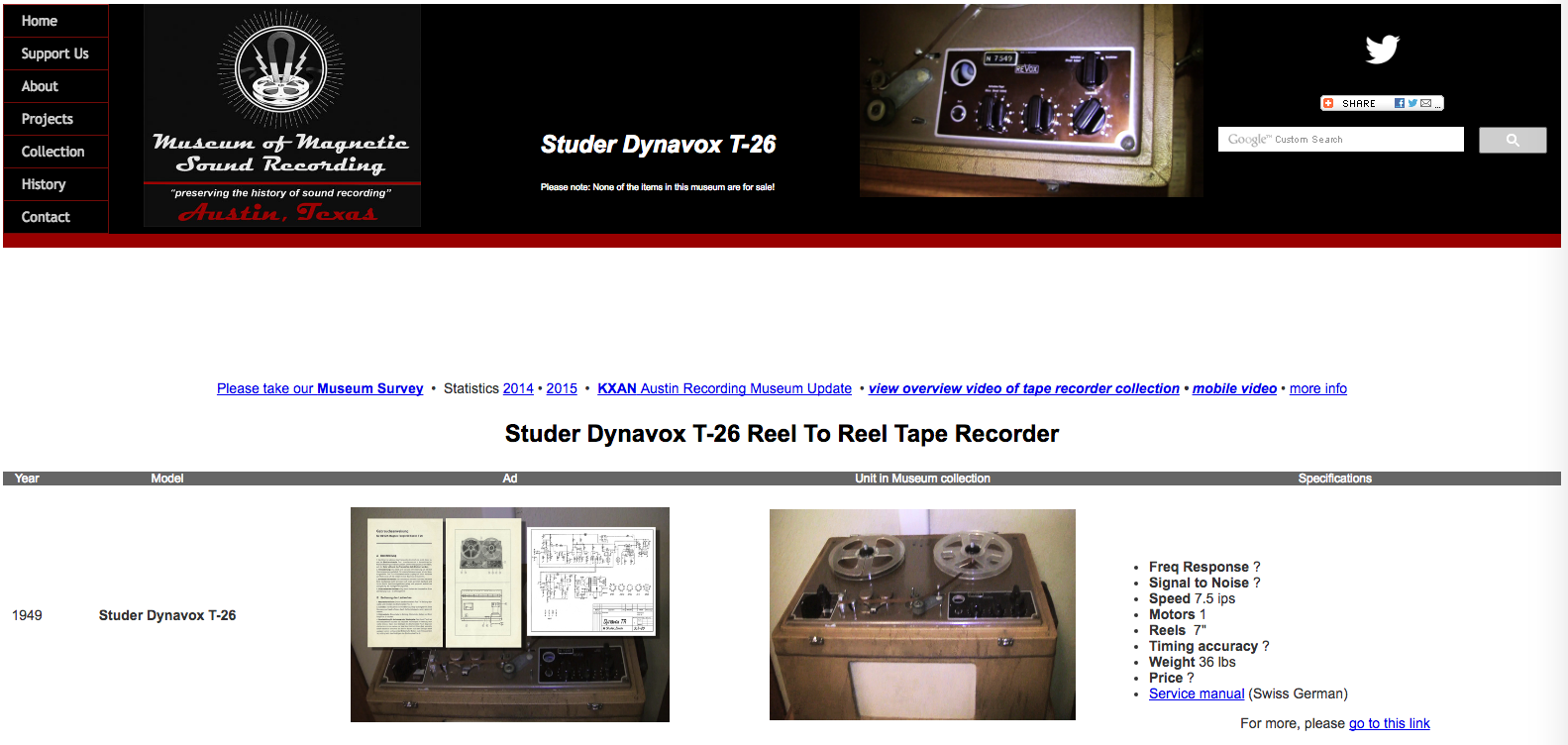

M: The Museum was created in an effort to preserve our vintage recording collection that was initiated in 1998 with the web site Reel2ReelTexas.com. My audio recording began professionally in 1964. Our production switched to video in the early 1990’s. In 1998, the collection began with a gift of an Edison cylinder player from my wife Chris. I missed having the tape recorders around, so we began acquiring the recorders I’d worked with and then several historically significant recorders were secured. One included the first professional magnetic tape recorder built in the US. It is the 1948 Ampex 200A #33 reel to reel tape recorder belonging to Capitol Records. We also have Willie first T-26 Dynavox tape recorder

GB: How are you funded and how can people view the collection?

M: Presently the Museum is funded by private donations. At this time we are functioning with volunteers and the collection is available to view on line. By appointment we provide private tours in our Studio/Museum.

GB: What is your favourite piece of (working) equipment and why?

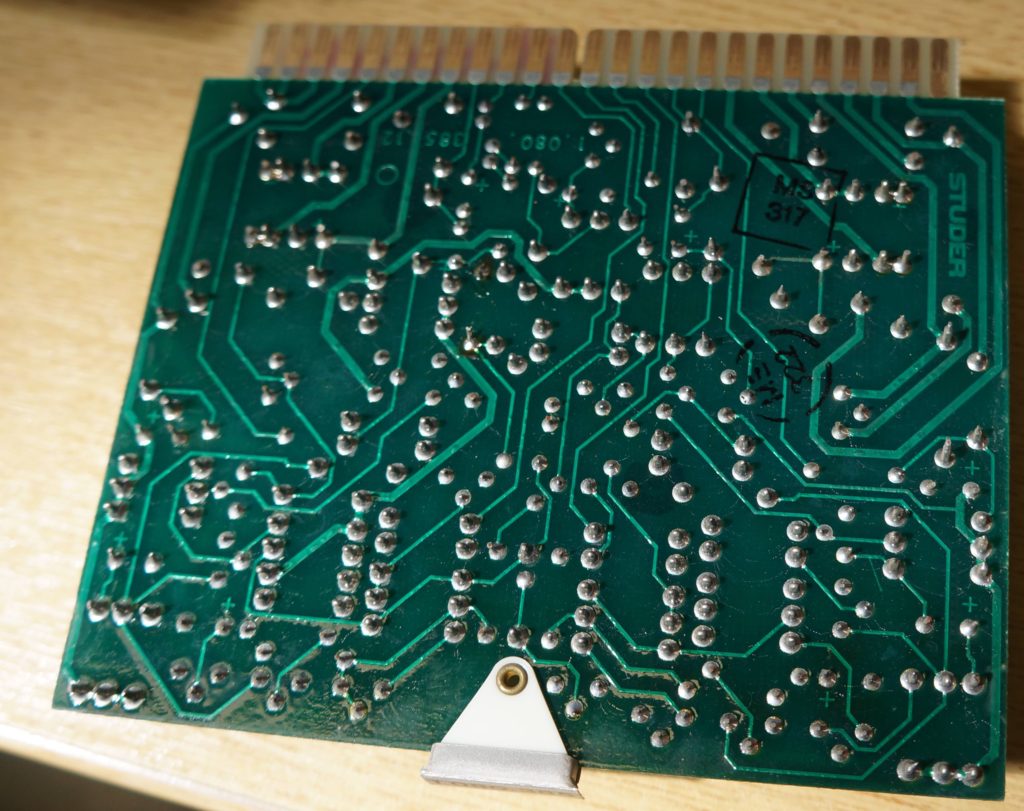

That’s difficult, however it is the Studer A807. It is in excellent condition and is one of the top Studer machines produced. Incidentally they had a wonderful museum saving their history. It disappeared after Harmon took Studer over.

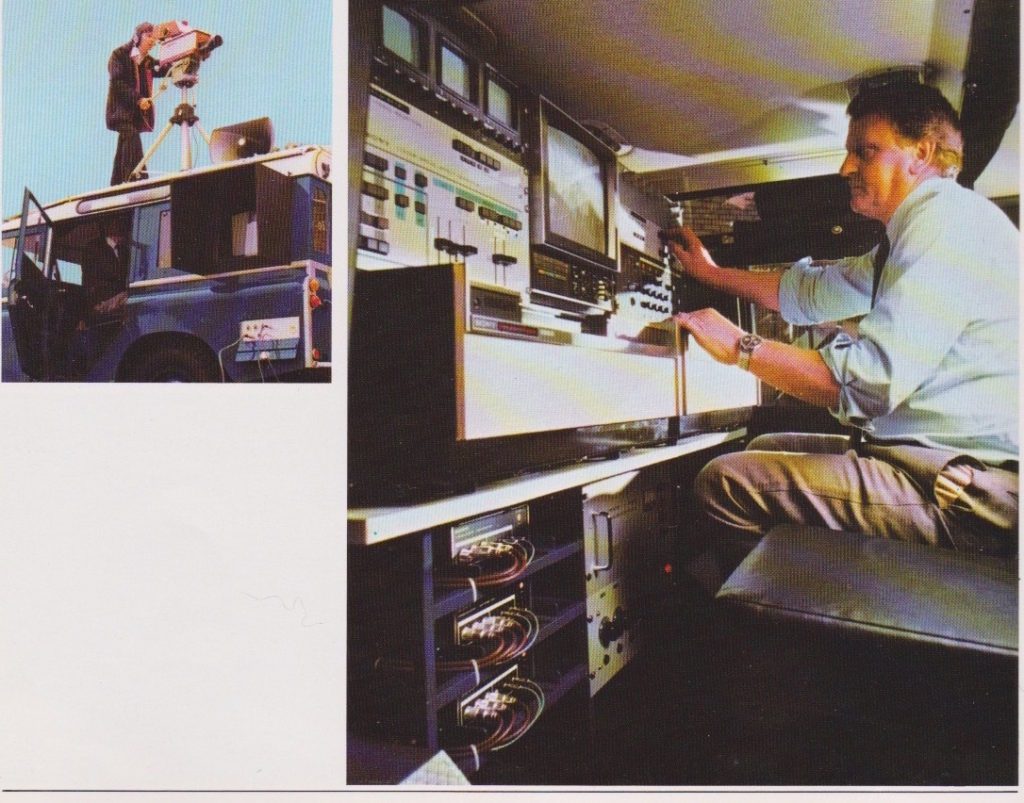

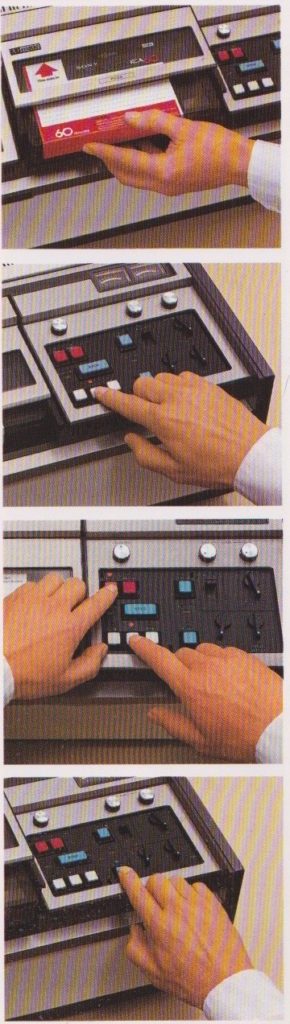

A tour of the Studer tape recorder and mixer ‘museum’ and a company history, recorded in Switzerland before the museum relocated to the Soundcraft Studer HQ in the UK.

GB:What is your favourite piece of (non-working) equipment and why?

M: There has to be two. 1) One would be the Ampex 200A #33 mentioned above. It just needs motor capacitors and will be operating soon. The 200A was overbuilt and weighed 240 lbs. While it originally belonged to Capitol Records, it eventually ended up with the San Francisco engineer/producer Leo De Gar Kulka. 2) The second is the Sony TC-772 half track 15 ips portable location recorder. It too needs motor capacitors. It was able to complete long high quality remote recordings and provided audio limiters, vari-speed and XLR connections. Beautiful design.

GB: What are the challenges of preserving magnetic sound recording? Is there a tension between keeping the machines working, and preserving their appearance as museum exhibits? Do you also seek to preserve the context surrounding the machines, i.e., marketing materials and so forth?

M: We strive to acquire the most complete and working examples of the items in the collection. Several, including another favourite – the Technics RS-1700, was traded up six times before we acquired a showroom quality recorder. The same was true for its dust cover and now both are “as new.” The working units need to be exercised regularly, oiled, heads cleaned and aligned and kept as clean as possible. I can go around the collection one day and everything is working well. The next day there may be a tour and some will always be finicky. The Swiffer duster is a valuable tool to keep the items clean. They are all in air conditioned rooms, but it is Texas and there will be dust.

The things we believe set our collection apart from others are: 1) most units work, are connected to sound systems and can be demonstrated, and 2) for each unit we have acquired and display not only manuals, but also ads, brochures, reviews and posters. All of these are scanned loaded to the web site.

Currently, we have over 1,000 images that are waiting to be processed and added to the site. Additionally, the Museum has most of the radio catalogs (Allied, Burstein Applebee, Lafayette, Olsen, Radio Shack, and more) and magazines (AES Journals, Engineer Producer, Db, Modern Recording, Tape Recorder, etc.) that advertised tape recorders from the 1930’s until they quit publishing. The recorder and microphone sections have also been scanned and added to the website.

GB: What kind of people come to the museum tours? What response do they have the material?

M: Most of the tours we provide are: folks who have been active in the recording industry; professional musicians; other collectors; radio and TV related folks; persons who have viewed the web site and are visiting in the Austin area; students; teachers; and people who are making a donation of a piece of equipment.

The responses have been overwhelming. As are visits to the web site. We maintain an ongoing web site survey asking if folks support the creation of our permanent public facility.

GB:Do you ever work with audio visual archivists to offer advice about preservation?

M: In the Spring of 2015, University of Texas at Austin’s School of Architecture’s Third Year Interior Design Class completed 11 interior designs for our Museum. One of the students won a $30,000 scholarship with her museum design. In that process, the UT School of Architecture provided significant information regarding preservation practices. The Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum’s Deputy Director, Margaret Koch, has been a supporter and mentor for our museum and provided many recommendations for preservation as we move forward. Just in the past couple of weeks, Peter Hammer, curator of the Ampex Museum prior to its donation to Stanford University, has agreed to provide our museum with preservation practices. Peter also envisions our re-creating the original Ampex Museum within our Museum of Magnetic Sound Recording. While we maintain the collection in a climate controlled studio, we will be more able to adhere to preservation practices when we have a permanent public facility.

GB:What do you see as the future of magnetic sound recording?

M: Magnetic sound recording will hopefully always be preserved and new discoveries integrated into the current knowledge. Magnetic cassettes have recently gained new attention (vinyl too). Maybe reel tape recorders will make a comeback. On our home page we show a new Revox A77 reel tape recorder being built by Akai. Otari still custom produces their classic MX-5050 reel tape recorder.

More importantly, professional recording studios around the globe are finding that many musicians love analogue recordings, so they are retaining, or acquiring analogue recorders. The evolutionary period of magnetic recording beginning in Germany in 1934 to the dawn of digital around 1982, spans an almost fifty year period. While the recording quality of vinyl had evolved and many still consider it of top reproduction quality, the advent of magnetic tape with the ability to edit and reproduce multiple copies was an incredible breakthrough.

GB:Your website is full of amazing information. What is the relationship between the online site and the physical museum?

M: Interesting question, because our intent has always been to provide as much web information as possible (far beyond the physical collection). In our recent conversations with Peter Hammer, the Ampex Museum curator, it is his belief that our preservation work: saving and scanning manuals, ads, catalogs, letters and all the supporting documentation, will actually be more significant than the actual machines themselves.

Peter states “When I say to people,“Digits last longer than molecules”, that tends to make them think twice about the extreme impermanence of physical collections, especially after I tell them horror stories like the Ampex Museum, the Anna Amalia Library fire in Weimar in 2004, the Cologne City Museum collapse in 2009, and now a new one for me, the sad demise of the Studer collection. Physical collections simply cannot withstand the vagaries of governmental agencies, corporations, private owners, the weather, or seismic stability!”

However, I am still passionate about creating a safe permanent public facility for the collection. There is much to be said for folks being able to actually view and operate a vintage recorder and view the process of making a recording.

GB: Anything else you want to say?

M: We have come to realize that to implement our vision, we will require a major donor who would enable the museum in the long term. We also found that preserving recording technology cannot compete with the museums that are preserving the musicians and their music. The Bob Bullock Texas History Museum considered displaying some of our magnetic recording items when they expanded their Texas music section. However they determined that folks were more likely to visit displays about Texas music. For that reason they went with the history of the Austin City Limits and items from music collections from the Rock ’n Roll Hall of Fame and the Grammy Museum.

——-

In closing, I thank you for this opportunity you’ve given me to reflect on what our goals are. We have responded to many promising opportunities, received significant verbal support, but have yet to bring the permanent facility to fruition. Due to last year’s heavy production schedule and some folks who did not follow through, I was discouraged. So last October I told our Board that maybe the museum had run its course. However, they would have none of that and encouraged us to push forward. Shortly after that we received a nice donation and I met Peter Hammer who has become an excellent resource who will be providing valuable Ampex documents and preservation consultation. So I feel very positive about our mission and will be happy to keep you posted as we progress.