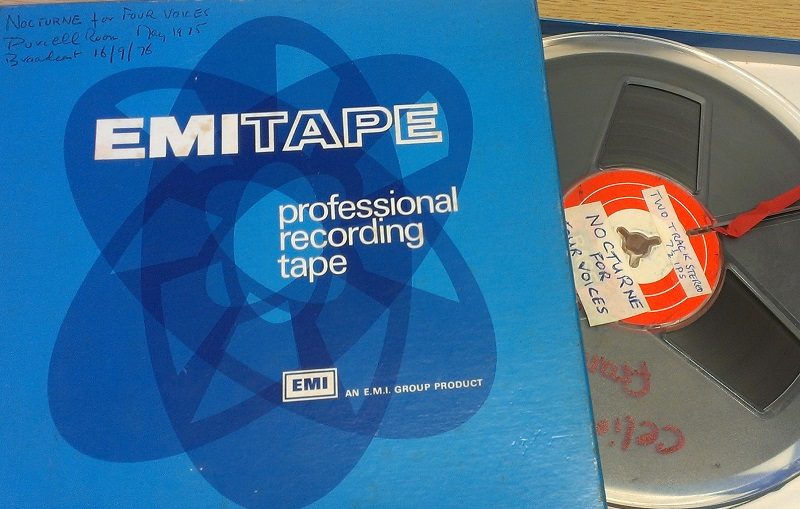

We have recently transferred a previously unpublished 3” ¼ inch tape recording of British 20th century composer Phyllis Tate’s Nocturn for Four Voices. The tape is a 2-track stereo recording made at 7.5 inches per second (in/s) at the Purcell Room in London’s Southbank Centre in 1975, and was broadcast on 16 September 1976.

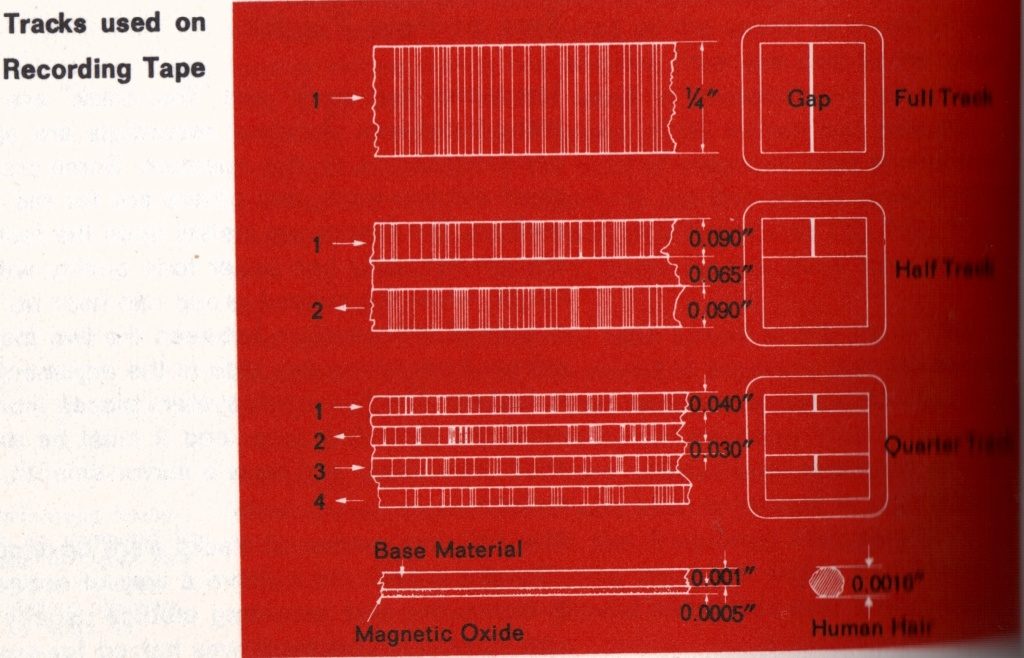

When migrating magnetic tape recordings to digital files there are several factors that can be considered to assess the quality of recording even before we play back the tape. One of these is the speed at which the tape was originally recorded.

Generally speaking, the faster the speed the better the reproduction quality when making the digital transfer. This is because higher tape speeds spread the recorded signal longitudinally over more tape area, therefore reducing the effects of dropouts and tape noise. The number of tracks recorded on the tape also has an impact on how good it sounds today. Simply put, the more information stored on the tape due to recording speed or track width, the better the transfer will sound.

The tape of Nocturn for Four Voices was however suffering from binder hydrolysis and therefore needed to be baked prior to play back. EMI tape doesn’t normally do this but as the tape was EMI professional it may well have used Ampex stock and / or have been back coated, thus making the binder more susceptible to such problems.

Remembering Phyllis Tate

Nocturn for Four Voices is an example of how Tate ‘composed for unusual combinations of instruments and voice.’ The composition includes ‘Bass Clarinet, Celeste, String Quartet and Double Bass’, music scholar Jane Ballantyne explains.

The tape was brought into us by Tate’s daughter, Celia Frank, who is currently putting the finishing touches to a web archive that, she hopes, will help contemporary audiences (re)discover her mother’s work.

Like many women musicians and artists, Phyllis Tate, who trained at the Royal Academy of Music, remains fairly obscure to the popular cultural ear.

This is not to say, of course, that her work did not receive critical acclaim from her contemporaries or posthumously. Indeed, it is fair to say that she had a very successful composing career. Both the BBC and the Royal Academy of Music, among others, commissioned compositions from Tate, and her work is available to hire or buy from esteemed music publishers Oxford University Press (OUP).

Edmund Whitehouse, who wrote a short biography of the composer, described her as ‘one of the outstanding British composers of her generation, she was truly her own person whose independent creative qualities produced a wide range of music which defy categorisation.’

Her music often comprised of contrasting emotional registers, lyrical sections and unexpected changes of direction. As a writer of operattas and choral music, with a penchant for setting poetry to music, her work is described by the OUP as the product of ‘an unusual imagination and an original approach to conventional musical forms or subjects, but never to the extent of being described as “avant-garde”.’

Tate’s music was very much a hit with iconic suffrage composer Ethel Smyth who, upon hearing Tate’s compositions, reputedly declared: ‘at last, I have heard a real woman composer.’ Such praise was downplayed by Tate, who tended to point to Smyth’s increased loss of hearing in later life as the cause of her enjoyment: ‘My Cello Concerto was performed soon afterwards at Bournemouth with Dame Ethel sitting in the front row banging her umbrella to what she thought was the rhythm of the music.’

While the dismissal of Smyth’s appreciation is tender and good humoured, the fact that Tate destroyed significant proportions of her work does suggest that at times she could have doubted her own abilities as a composer. Towards the end of her life she revealed: ‘I must admit to having a sneaking hope that some of my creations may prove to be better than they appear. One can only surmise and it’s not for the composer to judge. All I can vouch is this: writing music can be hell; torture in the extreme; but there’s one thing worse; and that is not writing it.’ As a woman composing in an overwhelmingly male environment, such hesitancies are perhaps an understandable expression of what literary scholars Gilbert and Gubar called ‘the anxiety of authorship.’

Tate’s work is a varied and untapped resource for those interested in twentieth century composition and the wider history of women composers. We wish Celia the best of luck in getting the website up and running, and hope that many more people will be introduced to her mother’s work as a consequence.

Thanks to Jane Ballantyne and Celia Frank for their help in writing this article.