Is this the end of tape as we know it? Maybe not quite yet, but October 1, 2014, will be a watershed moment in professional media production in the UK: it is the date that file format delivery will finally ‘go tape-less.’

Establishing end-to-end digital production will cut out what is now seen as the cumbersome use of video tape in file delivery. Using tape essentially adds a layer of media activity to a process that is predominantly file based anyway. As Mark Harrison, Chair of the Digital Production Partnership (DPP), reflects:

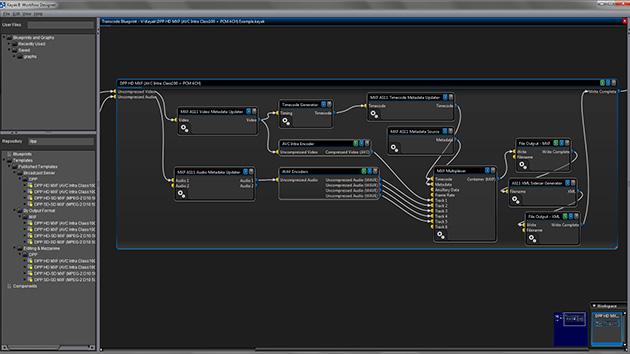

Example of a workflow for the DPP AS-11 standard

‘Producers are already shooting their programmes on tapeless cameras, and shaping them in tapeless post production environments. But then a strange thing happens. At the moment a programme is finished it is transferred from computer file to videotape for delivery to the broadcaster. When the broadcaster receives the tape they pass it to their playout provider, who transfers the tape back into a file for distribution to the audience.’

Founded in 2010, the DPP are a ‘not-for-profit partnership funded and led by the BBC, ITV and Channel 4 with representation from Sky, Channel 5, S4/C, UKTV and BT Sport.’ The purpose of the coalition is to help ‘speed the transition to fully digital production and distribution in UK television’ by establishing technical and metadata standards across the industry.

The transition to a standardised, tape-less environment has further been rationalised as a way to minimise confusion among media producers and help economise costs for the industry. As reported on Avid Blogs production companies, who often have to respond to rapidly evolving technological environments, are frantically preparing for deadline day. ‘It’s the biggest challenge since the switch to HD’, said Andy Briers, from Crow TV. Moreover, this challenge is as much financial as it is technical: ‘leading post houses predict that the costs of implementing AS-11 delivery will probably be more than the cost of HDCAM SR tape, the current standard delivery format’, writes David Wood on televisual.com.

Outlining the standard

Audio post production should now be mixed to the EBU R128 loudness standard. As stated in the DPP’s producer’s guide, this new audio standard ‘attempts to model the way our brains perceive sound: our perception is influenced by frequency and duration of sound’ (9).

In addition, the following specifications must be observed to ensure the delivery format is ‘technically legal.’

- HD 1920×1080 in an aspect ratio of 16:9 (1080i/25)

- AVC-I in MXF (Material Exchange Format) OP1a files to AS-11 specification

- DPP required metadata

- Photo Sensitive Epilepsy (flashing) testing to OFCOM standard/ the Harding Test

The shift to file-based delivery will require new kinds of vigilance and attention to detail in order to manage the specific problems that will potentially arise. The DPP producer’s guide states: ‘unlike the tape world (where there may be only one copy of the tape) a file can be copied, resulting in more than one essence of that file residing on a number of servers within a playout facility, so it is even more crucial in file-based workflows that any redelivered file changes version or number’.

Another big development within the standard is the important role performed by metadata, both structural (inherent to the file) and descriptive (added during the course of making the programme) . While broadcasters may be used to manually writing metadata as descriptive information on tape-boxes, they must now be added to the digital file itself. Furthermore, ‘the descriptive and technical metadata will be wrapped with the video and audio into a new and final AS-11 DPP MXF file,’ and if ‘any changes to the file are [made it is] likely to invalidate the metadata and cause the file to be rejected. If any metadata needs to be altered this will involve re-wrapping the file.’

Interoperability: the promise of digital technologies

The sector-wide agreement and implementation of digital file-delivery standards are significant because they represent a commitment to manufacturing full interoperability, an inherent potential of digital technologies. As French philosopher of technology Bernard Stiegler explains:

‘The digital is above all a process of generalised formalisation. This process, which resides in the protocols that enable interoperability, makes a range of diverse and varied techniques. This is a process of unification through binary code of norms and procedures that today allow the formalisation of almost everything: traveling in my car with a GPS system, I am connected through a digitised triangulation process that formalises my relationship with the maps through which I navigate and that transform my relationship with territory. My relationships with space, mobility and my vehicle are totally transformed. My inter-individual, social, familial, scholarly, national, commercial and scientific relationships are all literally unsettled by the technologies of social engineering. It is at once money and many other things – in particular all scientific practices and the diverse forms of public life.’

This systemic homogenisation described by Stiegler is called into question if we consider whether the promise of interoperability – understood here as different technical systems operating efficiently together – has ever been fully realised by the current generation of digital technologies. If this was the case then initiatives like the DPP’s would never have to be pursued in the first place – all kinds of technical operations would run in a smooth, synchronous matter. Amid the generalised formalisation there are many micro-glitches and incompatibilities that slow operations down at best, and grind them to a halt at worst.

With this in mind we should note that standards established by the DPP are not fully interoperable internationally. While the DPP’s technical and metadata standards were developed in close alliance with the US-based Advanced Media Workflow Association’s (AMWA) recently released AS-11 specification, there are also key differences.

As reported in 2012 by Broadcast Now Kevin Burrows, DPP Technical Standards Lead, said: ‘[The DPP standards] have a shim that can constrain some parameters for different uses; we don’t support Dolby E in the UK, although the [AMWA] standard allows it. Another difference is the format – 720 is not something we’d want as we’re standardising on 1080i. US timecode is different, and audio tracks are referenced as an EBU standard.’ Like NTSC and PAL video/ DVD then, the technical standards in the UK differ from those used in the US. We arguably need, therefore, to think about the interoperability of particular technical localities rather than make claims about the generalised formalisation of all technical systems. Dis-synchrony and technical differences remain despite standardisation.

The AmberFin Academy blog have also explored what they describe as the ‘interoperability dilemma’. They suggest that the DPP’s careful planning mean their standards are likely to function in an efficient manner: ‘By tightly constraining the wrapper, video codecs, audio codecs and metadata schema, the DPP Technical Standards Group has created a format that has a much smaller test matrix and therefore a better chance of success. Everything in the DPP File Delivery Specification references a well defined, open standard and therefore, in theory, conformance to those standards and specification should equate to complete interoperability between vendors, systems and facilities.’ They do however offer these words of caution about user interpretation: ‘despite the best efforts of the people who actually write the standards and specifications, there are areas that are, and will always be, open to some interpretation by those implementing the standards, and it is unlikely that any two implementations will be exactly the same. This may lead to interoperability issues.’

It is clear that there is no one simple answer to the dilemma of interoperability and its implementation. Establishing a legal commitment, and a firm deadline date for the transition, is however a strong message that there is no turning back. Establishing the standard may also lead to a certain amount of technological stability, comparable to the development of the EIAJ video tape standards in 1969, the first standardised format for industrial/non-broadcast video tape recording. Amid these changes in professional broadcast standards, the increasingly loud call for standardisation among digital preservationists should also be acknowledged.

For analogue and digital tapes however, it may well signal the beginning of an accelerated end. The professional broadcast transition to ‘full-digital’ is a clear indication of tape’s obsolescence and vulnerability as an operable media format.