This article is inspired by a collection of DVCAM tapes sent in by London-based cultural heritage organisation Sweet Patootee. Below we will explore several issues that arise from the transfer of DVCAM tapes, one of the many Digital Video formats that emerged in the mid-1990s. A second article will follow soon which focuses on the content of the Sweet Patootee archive, which is a fascinating collection of video-taped oral histories of 1 World War veterans from the Caribbean.

The main issue we want to explore below is the role error correction coding performs both in the composition of the digital video signal and during the preservation playback. We want to highlight this issue because it is often assumed that DVCAM, which first appeared on the market in 1996, is a fairly robust format.

The work we have done to transfer tapes to digital files indicates that error correction coding is working overdrive to ensure we can see and hear these recordings. The implication is that DVCAM collections, and wider DV-based archives, should really be a preservation priority for institutions, organisations and individuals.

Before we examine this in detail, let’s learn a bit about the technical aspects of error correction coding.

Error error error

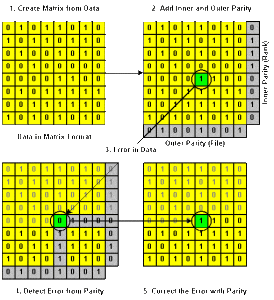

Error correction works through a process of prediction and calculation known as interpolation or concealment. It takes an estimation of the original recorded signal in order to re-construct parts of the data that have been corrupted. Corruption can occur due either to wear and tear, or insufficiencies in the original recorded signal.

Yet as Hugh Robjohns explains in the article ‘All About Digital Audio’ from 1998:

‘With any error protection system, if too many erroneous bits occur in the same sample, there is a risk of the error detection system failing, and in practice, most media failures (such as dropouts on tape or dirt on a CD), will result in a large chunk of data being lost, not just the odd data bit here and there. So a technique called interleaving is used to scatter data around the medium in such a way that if a large section is lost or damaged, when the data is reordered many smaller, manageable data losses are formed, which the detection and correction systems can hopefully deal with.’

There are many different types of error correction, and ‘like CD-ROMs, DV uses Reed-Solomon (RS) error detection and correction coding. RS can correct localised errors, but seldom can reconstruct data damaged by a dropout of significant size (burst error),’ explains this wonderfully detailed article about DV video formats archived on web archive.

The difference correction makes

Digital technology’s error correction is one of the key things that differentiate it from their analogue counterparts. As the IASA‘s Guidelines on the Production and Preservation of Digital Audio Objects (2009) explains:

‘Unlike copying analogue sound recordings, which results in inevitable loss of quality due to generational loss, different copying processes for digital recordings can have results ranging from degraded copies due to re-sampling or standards conversion, to identical “clones” which can be considered even better (due to error correction) than the original.’ (65)

To think that digital copies can, at times, exceed the quality of the original digital recording is both an astonishing and paradoxical proposition. After all we are talking about a recording that improves at the perceptual level, despite being compositionally damaged. It is important to remember that error correction coding cannot work miracles, and there are limits to what it can do.

Dietrich Schüller and Albrecht Häfner argue in the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives’s (IASA) Handling and Storage of Audio and Video Carriers (2014) that ‘a perfect, almost error free recording leaves more correction capacity to compensate for handling and ageing effects and, therefore, enhances the life expectancy.’ If a recording is made however ‘with a high error rate, then there is little capacity left to compensate for further errors’ (28-29).

The bizarre thing about error-correction coding then is the appearance of clarity it can create. And if there are no other recordings to compare with the transferred file, it is really hard to know what the recorded signal is supposed to look and sound like were its errors not being corrected.

When we watch the successfully migrated, error corrected file post-transfer, it matters little whether the original was damaged. If a clear signal is transmitted with high levels of error correction, the errors will not be transferred, only the clear image and sound.

Contrast this with a damaged analogue tape it would be clearly discernible on playback. The plus point of analogue tape is they do degrade gracefully: it is possible to play back an analogue tape recording with real physical deterioration and still get surprisingly good results.

Digital challenges

The big challenge working with any digital recordings on magnetic tape is to know when a tape is in poor condition prior to playback. Often tape will look fine and, because of error correction, will sound fine too until it stops working entirely.

How then did we know that the Sweet Patootee tapes were experiencing difficulties?

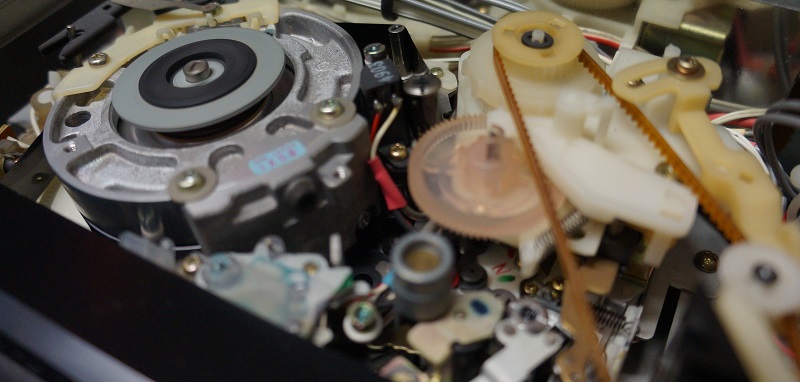

Professional DV machines such as our DVC PRO have a warning function that flashes when the error-correction coding is working at heightened levels. With our first attempt to play back the tapes we noticed that regular sections on most of the tapes could not be fixed by error correction.

The ingest software we use is designed to automatically retry sections of the tape with higher levels of data corruption until a signal can be retrieved. Imagine a process where a tape automatically goes through a playing-rewinding loop until the signal can be read. We were able to play back the tapes eventually, but the high level of error correction was concerning.

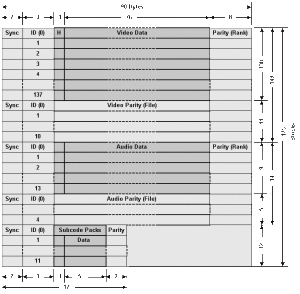

As this diagram makes clear, around 25% of the recorded signal in DVCAM is composed of subcode data, error detection and error correction.

DVCAM & Mis-alignment

It is not just the over-active error correction on DVCAMs that should send the alarm bells ringing.

Alan Griffiths from Bristol Broadcast Engineering, a trained SONY engineer with over 40 years experience working in the television industry, told us that early DVCAM machines pose particular preservation challenges. The main problem here is that the ‘mechanisms are completely different’ for earlier DVCAM machines which means that there is ‘no guarantee’ they will play back effectively on later models.

Recordings made on early DVCAM machines exhibit back tensions problems and tracking issues. This increases the likelihood of DV dropout on playback because a loss of information was recorded onto the original tape. The IASA confirm that ‘misalignment of recording equipment leads to recording imperfections, which can take manifold form. While many of them are not or hardly correctable, some of them can objectively be detected and compensated for.’

One possible solution to this problem, as with DAT tapes, is to ‘misalign’ the replay digital video tape recorder to match the misaligned recordings. However ‘adjustment of magnetic digital replay equipment to match misaligned recordings requires high levels of engineering expertise and equipment’ (2009; 72), and must therefore not be ‘tried at home,’ so to speak.

Our experience with the Sweet Patootee tapes indicates that DVCAM tapes are a more fragile format than is commonly thought, particularly if your DVCAM collection was recorded on early machines. If you have a large collection of DVCAM tapes we strongly recommend that you begin to assess the contents and make plans to transfer them to digital files. As always, do get in touch if you need any advice to develop your plans for migration and preservation.