At the recent Keeping Tracks symposium held at the British Library, AV scoping analyst Adam Tovell stated that

‘there is consensus internationally that we as archivists have a 10-20 year window of opportunity in which to migrate the content of our physical sound collections to stable digital files. After the end of this 10-20 year window, general consensus is that the risks faced by physical media mean that migration will either become impossible or partial or just too expensive.’

This point of view certainly corresponds to our experience at Greatbear. As collectors of a range of domestic and professional video and audio tape playback machines, we are aware of the particular problems posed by machine obsolescence. Replacement parts can be hard to come by, and the engineering expertise needed to fix machines is becoming esoteric wisdom. Tape degradation is of course a problem too. These combined factors influence the shortened horizon of magnetic tape-based media.

All may not be lost, however, if we are take heart from a recent article which reported the development of an exciting technology that will enable memory institutions to recover recordings made over 125 years ago on mouldy wax cylinders or acid-leaching lacquer discs.

IRENE (Image, Reconstruct, Erase Noise, Etc.), developed by physicist Carl Haber at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, is a software programme that ‘photographs the grooves in fragile or decayed recordings, stitches the “sounds” together with software into an unblemished image file, and reconstructs the “untouchable” recording by converting the images into an audio file.’

The programme was developed by Haber after he heard a radio show discuss the Library of Congress’ audio collections that were so fragile they risked destruction if played back. Haber speculated that the insights gained from a project he was working on could be used to recover these audio recordings. ‘“We were measuring silicon, why couldn’t we measure the surface of a record? The grooves at every point and amplitude on a cylinder or disc could be mapped with our digital imaging suite, then converted to sound.”’

For those involved in the development of IRENE, there was a strong emphasis on the benefits of patience and placing trust in the inevitable restorative power of technology. ‘It’s ironic that as we put more time between us and the history we are exploring, technology allows us to learn more than if we had acted earlier.’

Can such a hands-off approach be applied to magnetic tape based media? Is the 10-20 year window of opportunity described by Tovell above unnecessarily short? After all, it is still possible to playback wax cylinder recordings from the early 20th century which seem to survive well over long periods of time, and magnetic tape is far more durable than is commonly perceived.

In a fascinating audio recording made for the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, Nigel Bewley from the British Library describes how he migrated wax cylinder recordings that were made by Evans Pritchard in 1928-1930 and Diamond Jenness in 1911-1912. Although Bewley reveals his frustration in the preparation process, he reveals that once he had established the size of stylus and rotational speed of the cylinder player, the transfer was relatively straightforward.

You will note that in contrast with the recovery work made possible by IRENE, the cylinder transfer was made using an appropriate playback mechanism, examples of which can accessed on this amazing section of the British Library’s website (here you can also browse through images and information about disc cutters, magnetic recorders, radios, record players, CD players and accessories such as needle tins and headphones – a bit of a treasure trove for those inclined toward media archaeology).

Perhaps the development of the IRENE technology will mean that it will no longer be necessary to use such ‘authentic’ playback mechanisms to recover information stored on obsolete media. This brings us neatly to the question of emulation.

Emulation

If we assume that all the machines that play back magnetic tape become irrevocably obsolete in 10-20 years, what other potential extraction methods may be available? Is it possible that emulation techniques, commonly used in the preservation of born-digital environments, can be applied to recover the recorded information stored on magnetic tape?

In a recent interview Dirk Von Suchodoletz explains that:

‘Emulation is a concept in digital preservation to keep things, especially hardware architectures, as they were. As the hardware itself might not be preservable as a physical entity it could be very well preserved in its software reproduction. […] For memory institutions old digital artifacts become more easy to handle. They can be viewed, rendered and interacted-with in their original environments and do not need to be adapted to our modern ones, saving the risk of modifying some of the artifact’s significant properties in an unwanted way. Instead of trying to mass-migrate every object in the institution’s holdings, objects are to be handled on access request only, significantly shifting the preservation efforts.’

For the sake of speculation, let us imagine we are future archaeologists and consider some of the issues that may arise when seeking to emulate the operating environments of analogue-based tape media.

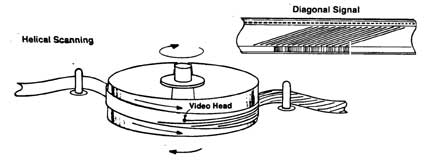

To begin with, without a working transport mechanism which facilitates the transmission of information, the emulation of analogue environments will need to establish a circuitry that can process the Radio Frequency (RF) signals recorded on magnetic tape. As Jonathan Sterne reflects, ‘if […] we say we have to preserve all aspects of the platform in order to get at the historicity of the media practice, that means archival practice will have to have a whole new engineering dimension to it.’

Yet with the emulation of analogue environments, engineering may have to be a practical consideration rather than an archival one. For example, some kind of transport mechanism would presumably have to be emulated through which the tape could be passed through. It would be tricky to lay the tape out flat and take samples of information from its surface, as IRENE’s software does to grooved media, because of the sheer length of tape when it unwound. Without an emulated transport mechanism, recovery would be time consuming and therefore costly, a point that Tovell intimates at the beginning of the article. Furthermore, added time and costs would necessitate even more complex selection and appraisal decisions on behalf of archivists managing in-operative magnetic tape-based collections. Questions about value will become fraught and most probably politically loaded. With an emulated transport mechanism, issues such as tape vulnerability and head clogs, which of course impact on current migration practices, would come into play.

Audio and video differences

On a technical level emulation may be vastly more achievable for audio where the signal is recorded using a longitudinal method and plays back via a relatively simple process. Audio tape is also far less propriety than video tape. On the SONY APR-5003V machine we use in the Greatbear Studio for example, it is possible to play back tapes of different sizes, speeds, brands, and track formations via adjustments of the playback heads. Such versatility would of course need to be replicated in any emulation environment.

Unlike audio, video tape circuitry is more propriety and therefore far less inter-operable. You can’t play a VHS tape on a U-Matic machine, for example. Numerous mechanical infrastructures would therefore need to be devised which correspond with the relevant operating environments – one size fits all would (presumably) not be possible.

A generic emulated analogue video tape circuit may be created, but this would only capture part of the recorded signal (which, as we have explored elsewhere on the blog, may be all we can hope for in the transmission process). If such systems are to be developed it is surely imperative that action is taken now while hardware is operative and living knowledge can be drawn upon in order to construct emulated environments in the most accurate form possible.

While hope may rest in technology’s infinite capacity to take care of itself in the end, excavating information stored on magnetic tape presents far more significant challenges when compared with recordings on grooved media. There is far more to tape’s analogue (and digital) circuit than a needle oscillating against a grooved inscription on wax, lacquer or vinyl.

The latter part of this article has of course been purely speculative. It would be fascinating to learn about projects attempting to emulate the analogue environment in software – please let us know if you are involved in anything in the comments below.