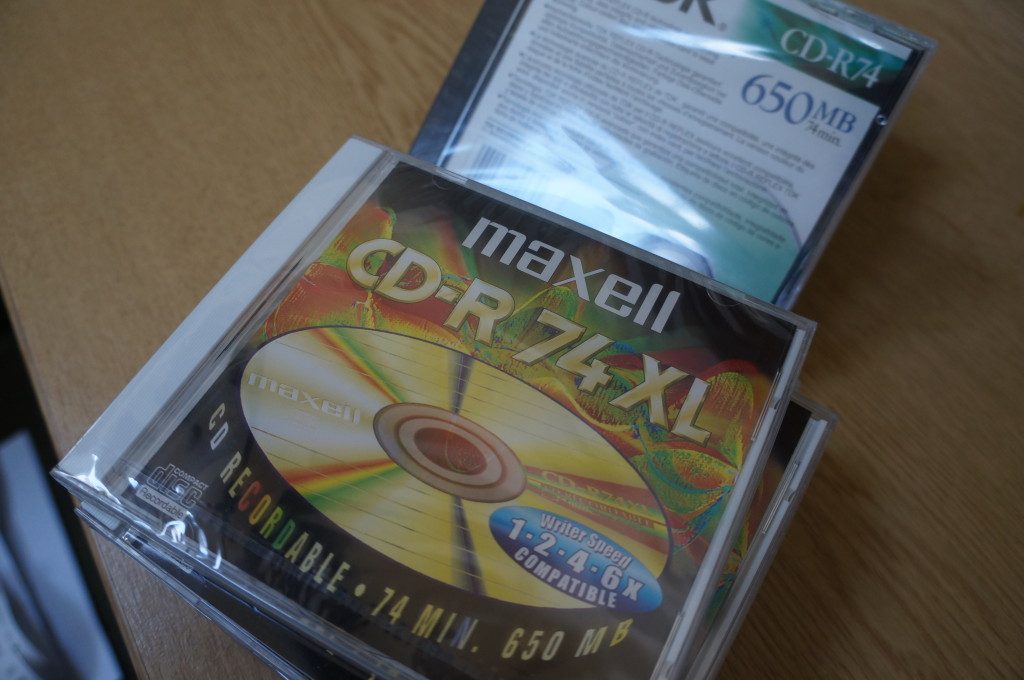

Often customers ask us to deliver their transferred sound files on CD, in effect an audio CD-R of the transfer.

Although these recordings can still be high resolution there remains a world of difference—in an archival sense—between a CD-R, burnt on a computer drive (however high the quality of drive and disc), and CD recordings made in the context of the professional music industry.

The CD format is far from ‘obsolete,‘ and recent history has shown us repeatedly that formats deemed ‘dead’, such as vinyl or the audio cassette, can become fashionable again.

Yet when it comes to the preservation of your audio and video archives, it is a good idea to think about this material differently. It is one thing to listen to your favourite artist on CD, in other words, but that precious family recording of your Grandfather discussing his life history on a CD-R is different.

Because of this, we believe that supplying customers with digital files, on hard drive on USB stick is, in 2016 and beyond, a much better option. Holding a recording in physical form in the palm of your hand can be reassuring. Yet if you’ve transferred valuable recordings to ensure you can listen to them once…

Why risk having to do it again?

CD-Rs are, quite simply, not a reliable archival medium. Even optical media that claims spectacular longevity, such as the 1000 year proof M-Disc, are unlikely to survive the warp and weft of technological progress.

Exposure to sunlight can render CD-Rs and DVDs unreadable. If the surface of a CD-R becomes scratched, its readability is severely compromised.

There is also the issue of compatibility between burners and readers, as pointed out in the ARSC Guide to Audio Preservation:

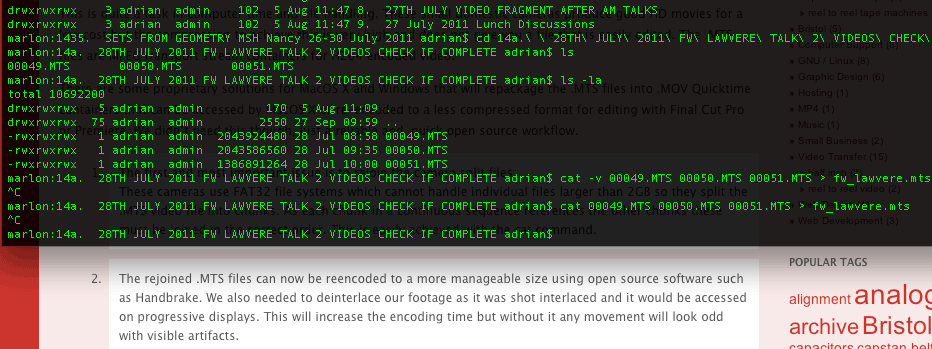

There are standards for CD-R discs to facilitate the interchange of discs between burners and readers. However, there are no standards covering the burners or readers themselves, and the disc standards do not take preservation or longevity into consideration. Several different burning and reading speeds were developed, and earlier discs or burners are not compatible with later, faster speeds. As a result, there is considerable variability in whether any given disc can be read by any given reader (30).

Furthermore, disc drives on computers are becoming less common. It would therefore be unwise to exclusively store valuable recordings on this medium if you want them to have the best chance of long time survival.

In short, the CD-R is just another obsolete format (and an unreliable one at that). Of course, once you have the digital files there is nothing stopping you from making access copies on CD-R for friends and family. Having the digital files as source format gives you greater flexibility to share, store and duplicate your archival material.

File-based preservation

The threat of obsolescence haunts all digital media, to a degree. There is no one easy, catchall solution to preserve the media we produce now which is, almost exclusively, digital.

Yet given the reality of the situation, and the desire people harbour to return to recordings that are important to them, it makes sense that non-experts gain a basic understanding of what digital preservation may entail for them.

There are a growing amount of online resources for people who want to get familiar with the rudiments of personal digital archiving. It would be very difficult to cover all the issues below, so comments are limited to a few observations.

It is true that managing a digital collection requires a different kind of attitude – and skill set – to analogue archiving that is far less labour intensive. You cannot simply transfer your digital files onto a hard drive, put it on the shelf and forget about it for ten-fifteen years. If you were to do this, there is a very real possibility the file could not be opened when you return to it.

Screenshot taken from the DPC guide to Personal Digital Archiving

As Gabriela Redwine explains in the Digital Preservation Coalition’s Technology Watch Report on Personal Digital Archiving, ‘the reality of ageing hardware and software requires us to be actively attuned to the age and condition of the digital items in our care.’ The emerging personal digital archivist therefore needs to learn how to practice actively engaging with their collections if their digital files are to survive in the long term.

Getting to grips with digital preservation, even at a basic level, will undoubtedly involve learning a variety of new skills, terms and techniques. Yet there are some simple, and fairly non-technical, things you can do to get started.

The first point to emphasise is the importance of saving files in more than one location. This is probably the most basic principle of digital preservation.

The good news about digital files is they can be moved, copied and shared with family and friends all over the world with comparable ease. So if there is a fire in one location, or a computer fails in another, it is likely that the file will still be safe in the other place where it is stored.

Employing consistent and clear file naming is also very important, as this enables files to be searched for and found easily.

Beyond this, things get a little more complicated and a whole lot more computer-based. We move into the more specialist area of digital preservation with its heady language of metadata, checksums and emulation, among other terms.

The need for knowledge and competencies

The reality is that as we move deeper into the digital, file-based future, ordinary people will need to adopt existing preservation tools if they are to learn how to manage their digital collections in a more direct and informed way.

Take, for example, the often cited recommendation for people to migrate or back up their collections on different media at annual or bi-annual intervals. While this advice may be sound, should people be doing this without profiling the file integrity of their collections first? What’s the point in migrating a collection of files, in other words, if half of those files are already corrupted?

In such instances as these, the everyday person may wish to familiarise themselves with existing software tools that can be used to assess and identify potential problems with their personal collections.

DROID (Digital Record Object IDentification), for example, a software tool developed by the UK National Archives, profiles files in your collection in order to facilitate ‘digital continuity’, ‘the ability to use digital information in the way that you need, for as long as you need.’

The open source software can identify over 200 of the most common document, image, audio and video files. It can help tell you what versions you have, their age and size, and when they were last changed. It can also help you find duplicates, and manage your file space more efficiently. DROID can be used to scan individual files or directories, and produces this information in a summary report. If you have never assessed your files before it may prove particularly useful, as it can give a detailed overview.

A big draw back of DROID is that it requires programming knowledge to install, so is not immediately accessible to those without such specialist skills. Fixity is a more user-friendly open source software tool that can enable people to monitor their files, tracking file changes or corruptions. Tools like Fixity and DROID do not ensure that digital files are preserved on their own; they help people to identify and manage problems within their collections. A list of other digital preservation software tools can be found here.

For customers of Greatbear, who are more than likely to be interested in preserving audiovisual archives, AV Preserve have collated a fantastic list of tools that can help people both manage and practice audiovisual preservation. For those interested in the different scales of digital preservation that can be employed, the NDSA (National Digital Stewardship Alliance) Levels of Preservation offers a good overview of how a large national institution envisions best practice.

Tipping Points

We are, perhaps, at a tipping point for how we play back and manage our digital data. The 21st century has been characterised by the proliferation of digital artefacts and memories. The archive, as the fundamental shaper of individual and community identities, has taken central stage in our lives.

With this unparalleled situation, new competencies and confidences certainly need to be gained if the personal archiving of digital files is to become an everyday reality at a far more granular and empowered level than is currently the norm.

Maybe, one day, checking the file integrity of one’s digital collection will be seen as comparable to other annual or bi-annual activities, such as going to the dentist or taking the car for its MOT.

We are not quite there yet, that much is certain. This is largely because companies such as Google make it easy for us to store and efficiently organise personal information in ways that feel secure and manageable. These services stand in stark contrast to the relative complexity of digital preservation software, and the computational knowledge required to install and maintain it (not to mention the amount of time it could take to manage one’s digital records, if you really dedicated yourself to it).

Growing public knowledge about digital archiving, the desire for knowledge and new competencies, as well as the pragmatic fact that digital archives are easier to manage in file-based systems, may encourage the gap between professional digital preservation practices and the interests of everyday, digital citizens, to gradually close over time. Dialogue and greater understanding is most certainly needed if we are to move forward from the current context.

Greatbear want to be part of this process by helping customers have confidence in file-based delivery, rather than rely on formats that are obsolete, of poorer quality and counter-intuitive to the long term preservation of audio visual archives.

We are, as ever, happy to explain the issues in more detail, so please do contact us if there are issues you want to discuss.

We also provide a secure CD to digital file transcription service: Digital audio (CD-DA), data (CD-ROM), audio and data write-once (CD-R) and rewritable media (CD-RW) disc transfer.