At Greatbear, we carefully restore and transfer to digital file all types of content recorded to Digital Audio Tape (DAT), and can support all sample rate and bit depth variations.

This post focuses on some of the problems that can arise with the transfer of DATs.

An immature recording method (digital) on a mature recording format (magnetic tape), the audio digital recording revolution was never going to get it right first time (although DATs were not of course the first digital recordings made on tape).

Indeed, at a meeting of audio archivists held in 1995, there was a consensus even then that DAT was not, and would never be, a reliable archival medium. One participant stated: ‘we have tapes from 1949 that sound wonderful,’ and ‘we have tapes from 1989 that are shot to hell.’ And that was nearly twenty years ago! What chances do the tapes have now?

A little DAT history

Before we explore that, let’s have a little DAT history.

SONY introduced Digital Audio Tapes (DATs) in 1987. At roughly half the size of an analogue cassette tape, DAT has the ability to record at higher, equal or lower sampling rates than a CD (48, 44.1 or 32 kHz sampling rate respectively) at 16 bit quantization.

Although popular in Japan, DATs were never widely adopted by the majority of consumer market because they were more expensive than their analogue counterparts. They were however embraced in professional recording contexts, and in particular for recording live sound.

It was recording industry paranoia, particularly in the US, that really sealed the fate of the format. With its threatening promise of perfect replication, DAT tapes were subject to an unsuccessful lobbying campaign by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). RIAA saw DATs as the ultimate attack on copyright law and pressed to introduce the Digital Audio Recorder Copycode Act of 1987.

This law recommended that each DAT machine had a ‘copycode’ chip installed that could detect whether prerecorded copyrighted music was being replicated. The method employed a notch filter that would subtly distort the quality of the copied recording, thus sabotaging acts of piracy tacitly enabled by the DAT medium. The law was however not passed, and compromises were made, although the US Audio Home Recording Act of 1992 imposed taxes on DAT machines and blank media.

How did they do ‘dat?

Like video tape recorders, DAT tapes use a rotating head and helical scan method to record data. The helical scan can, however, pose real problems for the preservation transfers of DAT tapes because it makes it difficult to splice the tape together if it becomes sticky and snaps during the tape wind. With analogue audiotape, which records information longitudinally, it is far more possible to splice the tape together and continue the transfer without risking irrevocable information loss.

Another problem posed by the helical scan method is that such tapes are more vulnerable to tape pack and backing deformation, as the CLIR guide explain:

‘Tracks are recorded diagonally on a helical scan tape at small scan angles. When the dimensions of the backing change disproportionately, the track angle will change for a helical scan recording. The scan angle for the record/playback head is fixed. If the angle that the recorded tracks make to the edge of the tape do not correspond with the scan angle of the head, mistracking and information loss can occur.’

When error correction can’t correct anymore

Our SONY PCM 7030 professional DAT machine, pictured opposite, has a ‘playback condition’ light that flashes if an error is present. On sections of the tape where quality is really bad the ‘mute’ light can flash to indicate that the error correction technology can’t fix the problem. In such cases drop outs are very audible. Most DAT machines did not have such a facility however, and you only knew there was a problem when you heard the glitchy-clickety-crackle during playback when, of course, it was too late do anything about it.

The bad news for people with large, yet to be migrated DAT archives is that the format is ‘particularly susceptible to dropout. Digital audio dropout is caused by a non-uniform magnetic surface, or a malfunctioning tape deck. However, because the magnetically recorded information is in binary code, it results in a momentary loss of data and can produce a loud transient click or worse, muted audio, if the error correction scheme in the playback equipment cannot correct the error,’ the wonderfully informative A/V Artifact Atlas explains.

Given the high density nature of digital recordings on narrow magnetic tape, even the smallest speck of dust can cause digital audio dropouts. Such errors can be very difficult to eliminate. Cleaning playback heads and re-transferring is an option, but if the dropout was recorded at the source or the surface of tape is damaged, then the only way to treat irregularities is through applying audio restoration technologies, which may present a problem if you are concerned with maintaining the authenticity of the original recording.

Listen to this example of what a faulty DAT sounds like

Play back problems and mouldy DATs

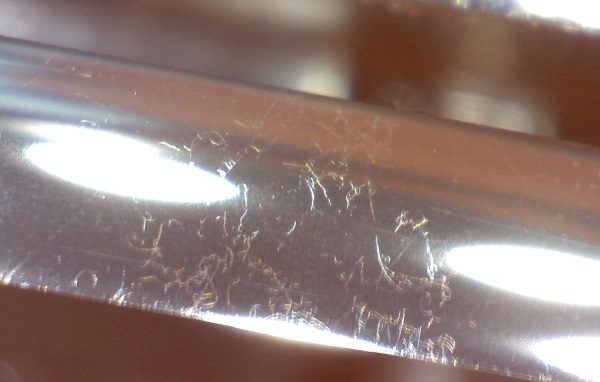

Mould growth on the surface of DAT tape

A big problem with DAT transfers is actually being able to play back the tapes, or what is known in the business as ‘DAT compatibility.’ In an ideal world, to get the most perfect transfer you would play back a tape on the same machine that it was originally recorded on. The chances of doing this are of course pretty slim. While you can play your average audio cassette tape on pretty much any tape machine, the same cannot be said for DAT tapes. Often recordings were made on misaligned machines. The only solution for playback is, Richard Hess suggests, to mis-adjust a working machine to match the alignment of the recording on the tape.

As with any archival collection, if it is not stored in appropriate conditions then mould growth can develop. As mentioned above, DAT tapes are roughly half the size of the common audiocassette and the tape is thin and narrow. This makes them difficult to clean because they are mechanically fragile. Adapting a machine specifically for the purposes of cleaning, as we have done with our Studer machine, would be the most ideal solution. There is, however, not a massive amount of research and information about restoring mouldy DATs available online even though we are seeing more and more DAT tapes exhibiting this problem.

As with much of the work we do, the recommendation is to migrate your collections to digital files as soon as possible. But often it is a matter of priorities and budgets. From a technical point of view, DATs are a particularly vulnerable format. Machine obsolescence means that compared to their analogue counterparts, professional DAT machines will be increasingly hard to service in the long term. As detailed above, glitchy dropouts are almost inevitable given the sensitivity and all or nothing quality of digital data recorded on magnetic tape.

It seems fair to say that despite being meant to supersede analogue formats, DATs are far more likely to drop out of recorded sound history in a clinical and abrupt manner.

They therefore should be a high priority when decisions are made about which formats in your collection should be migrated to digital files immediately, over and above those that can wait just a little bit longer.