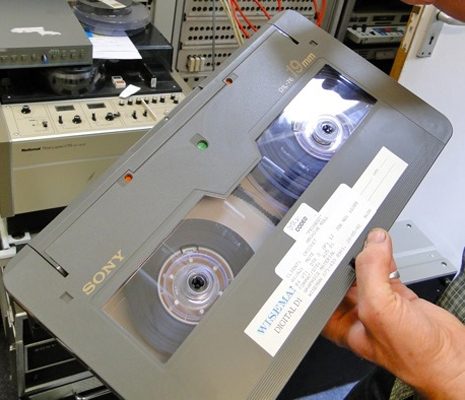

Large D-1 cassette dimensions: 36.5 x 20.3 x 3.2cm

D-2 cassette dimensions: 25.4 x 14.9 x 3cm

D-3 cassette size M: 21.2 x 12.4 x 2.5 cm

At Greatbear we carefully restore and transfer D-1, D-2, D-3, D-5, D-9 and Digital-S tapes to digital file at archival quality.

Early digital video tape development

Behind every tape (and every tape format) lie interesting stories, and the technological wizardry and international diplomacy that helped shape the roots of our digital audio visual world are worth looking into.

In 1976, when the green shoots of digital audio technology were emerging at industry level, the question of whether Video Tape Recorders (VTRs) could be digitised began to be explored in earnest by R & D departments based at SONY, Ampex and Bosch G.m.b.H. There was considerable scepticism among researchers about whether digital video tape technology could be developed at all because of the wide frequency required to transmit a digital image.

In 1977 however, as reported on the SONY website, Yoshitaka Hashimoto and team began to intensely research digital VTRs and 'in just a year and a half, a digital image was played back on a VTR.'

Several years of product development followed, shaped, in part, by competing regional preferences. As Jim Slater argues in Modern Television Systems (1991): 'much of the initial work towards digital standardisation was concerned with trying to find ways of coping with the three very different colour subcarrier frequencies used in NTSC, SECAM and PAL systems, and a lot of time and effort was spent on this' (114).

Establishing a standard sampling frequency did of course have real financial consequences, it could not be randomly plucked out the air: the higher the sampling frequency, the greater overall bit rate; the greater overall bit rate, the more need for storage space in digital equipment. In 1982, after several years of negotiations, a 13.5 MHz sampling frequency was agreed. European, North American, 'Japanese, the Russians, and various other broadcasting organisations supported the proposals, and the various parameters were adopted as a world standard, Recommendation 601 [a.k.a. 4:2:2 DTV] standard of the CCIR [Consultative Committee for International Radio, now International Telecommunication Union]' (Slater, 116).

The 4:4:2 DTV was an international standard that would form the basis of the (almost) exclusively digital media environment we live in today. It was 'developed in a remarkably short time, considering its pioneering scope, as the worldwide television community recognised the urgent need for a solid basis for the development of an all-digital television production system', write Stanley Baron and David Wood

Once agreed upon, product development could proceed. The first digital video tape, the D-1, was introduced on the market in 1986. It was an uncompressed component video which used enormous bandwidth for its time: 173 Mbit/sec (bit rate), with maximum recording time of 94 minutes.

BTS DCR 500 D-1 video recorder at Greatbear studio

As Slater writes: 'unfortunately these machines are very complex, difficult to manufacture, and therefore very expensive […] they also suffer from the disadvantage that being component machines, requiring luminance and colour-difference signals at input and output, they are difficult to install in a standard studio which has been built to deal with composite PAL signals. Indeed, to make full use of the D-1 format the whole studio distribution system must be replaced, at considerable expense' (125).

Being forced to effectively re-wire whole studios, and the considerable risk involved in doing this because of continual technological change, strikes a chord with the challenges UK broadcast companies face as they finally become 'tapeless' in October 2014 as part of the Digital Production Partnership's AS-11 policy.

Sequels and product development

As the story so often goes, D-1 would soon be followed by D-2. Those that did make the transition to D-1 were probably kicking themselves, and you can only speculate the amount of back injuries sustained getting the machines in the studio (from experience we can tell you they are huge and very heavy!)

It was fairly inevitable a sequel would be developed because even as the D-1 provided uncompromising image quality, it was most certainly an unwieldy format, apparent from its gigantic size and component wiring. In response a composite digital video, the D-2, was developed by Ampex and introduced in 1988.

In this 1988 promotional video, you can see the D-2 in action. Amazingly for our eyes and ears today the D-2 is presented as the ideal archival format. Amazing for its physical size (hardly inconspicuous on the storage shelf!) but also because it used composite video signal technology. Composite signals combine on one wire all the component parts which make up a video signal: chrominance (colour, or Red Green, Blue - RGB) and luminance (the brightness or black and white information, including grayscale).

While the composite video signal used lower bandwidth and was more compatible with existing analogue systems used in the broadcast industry of the time, its value as an archival format is questionable. A comparable process for the storage we use today would be to add compression to a file in order to save file space and create access copies. While this is useful in the short term it does risk compromising file authenticity and quality in the long term. The Ampex video is fun to watch however, and you get a real sense of how big the tapes were and the practical impact this would have had on the amount of time it took to produce TV programmes.

Enter the D-3

Following the D-2 is the D-3, which is the final video tape covered in this article (although there were of course the D5 and D9.)

The D-3 was introduced by Panasonic in 1991 in order to compete with Ampex's D-2. It has the same sampling rate as the D-2 with the main difference being the smaller shell size.

The D-3's biggest claim to fame was that it was the archival digital video tape of choice for the BBC, who migrated their analogue video tape collections to the format in the early 1990s. One can only speculate that the decision to take the archival plunge with the D-3 was a calculated risk: it appeared to be a stable-ish technology (it wasn't a first generation technology and the difference between D-2 and D-3 is negligible).

The extent of the D-3 archive is documented in a white paper published in 2008, D3 Preservation File Format, written by Philip de Nier and Phil Tudor: 'the BBC Archive has around 315,000 D-3 tapes in the archive, which hold around 362,000 programme items. The D-3 tape format has become obsolete and in 2007 the D-3 Preservation Project was started with the goal to transfer the material from the D-3 tapes onto file-based storage.'

Tom Heritage, reporting on the development of the D3 preservation project in 2013/2014, reveals that 'so far, around 100,000 D3 and 125,000 DigiBeta videotapes have been ingested representing about 15 Petabytes of content (single copy).'

It has then taken six years to migrate less than a third of the BBC's D-3 archive. Given that D-3 machines are now obsolete, it is more than questionable whether there are enough D-3 head hours left in existence to read all the information back clearly and to an archive standard. The archival headache is compounded by the fact that 'with a large proportion of the content held on LTO3 data tape [first introduced 2004, now on LTO-6], action will soon be required to migrate this to a new storage technology before these tapes become difficult to read.' With the much publicised collapse of the BBC's (DMI) digital media initiative in 2013, you'd have to very strong disposition to work in the BBC's audio visual archive department.

The roots of the audio visual digital world

The development of digital video tape, and the international standards which accompanied its evolution, is an interesting place to start understanding our current media environment. They are also a great place to begin examining the problems of digital archiving, particularly when file migration has become embedded within organisational data management policy, and data collections are growing exponentially.

While the D-1 may look like an alien-techno species from a distant land compared with the modest, immaterial file lists neatly stored on hard drives that we are accustomed to, they are related through the 4:2:2 sample rate which revolutionised high-end digital video production and continues to shape our mediated perceptions.

Preserving early digital video formats

More more information on transferring D-1, D-2, D3, D-5, D-5HD & D-9 / Digital S from tape to digital files, visit our digitising pages for:

D-1 (Sony) component and D-2 (Ampex) composite 19mm digital video cassettes

Composite digital D-3 and uncompressed component digital D-5 and D-5HD (Panasonic) video cassettes