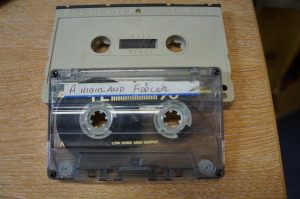

The recent arrival of a Grundig C 100 (DC-International) cassette in the Greatbear studio has been an occasion to explore the early history of the compact cassette.

The compact cassette has gained counter-cultural kudos in recent times, and more about that later, but once upon a time the format was the new kid on the block.

The audio cassette was revolutionary for several reasons, an important one being its compact size. The compact cassette, introduced by Dutch company Philips in 1963 could be held in the palm of your hand, while its closest neighbour in media history, the RCA Sound Tape cartridge (1958-1964), needed to be held with two.

The compact cassette also offered a more user-friendly experience for the consumer.

Whereas reel-to-reel tape had to be threaded manually through the tape transport, all the user of a compact cassette tape machine had to do was insert a tape in a machine and press play.

Format Wars

One of the less-emphasised histories of the compact cassette is the alternative cassette standards that were vying for market domination alongside Philips in the early 1960s.

One alternative was the DC-International system developed by the German company Grundig who at that time were a leading manufacturer of tape, radio and Hi-Fi systems.

In 1965 Grundig introduced its first cassette recorder, the C 100, which used the Double Cassette (DC) International system. The DC-International used two-reels within the cassette shell similar to the Compact-System promoted by Philips. There were, however, important differences between the two standards.

The DC-International standard used a larger cassette shell (120 x 77 x 12mm) and recorded at a speed of 2 inches per second. The Compact-System was smaller (100 × 63 × 12mm) and recorded at 1⅞ in/s.

Fervent global competition shaped audio cassette production in the mid-1960s.

Grundig’s DC-International was effectively (and rapidly) ousted from the market by Philips’ ‘open’ licensing strategy.

Eric D. Daniel and C. Denis Mee explain that

‘From the beginning Philips pursued a strategy of licensing its design as widely as possible. According to Frederik Philips, president of the firm at the time, this policy was the brainchild of Mr. Hartong, a member of the board of management. Hartong believed that Philips should allow other manufacturers access to the design, turning the compact cassette into a world product….Despite initial plans to charge a fee, Philips eventually decided to offer the license for free to any firm willing to produce the design. Several firms adopted the compact cassette almost immediately, including many Japanese manufacturers.’ [1]

The outcome of this licensing strategy was a widespread, international adoption of Philips’ compact cassette standard.

In Billboard on 16 September 1967 it was reported: ‘Philips has scored a critical victory on the German market for its “Compact-System”, which now seems certain to have uncontested leadership. Teldec has switched from the DC-International system to the Philips system, and Grundig, the major manufacturer of the DC-International system, announced that it will also start manufacturing cassette players for the Philips system.’

Cassettes today

The portable, user-friendly compact cassette has proved to be a resilient format. Despite falling foul to the digital march of progress in the early 1990s, the past couple of years have been defined by claims that cassettes are back and (almost) cool again.

Although the Recording Industry Association of America have denied reports they are tracking cassette sales again, it is clear that ‘a small, but engaged niche audience… is steadily growing’ for tape-based releases.

Whether that audience is gorging on tapes from do it yourself tape labels or sampling the delights of Justin Bieber’s latest album, cassettes are a hit for low-budget music-makers and status-bearers alike.

Compact Cassette Preservation

Amid this cassette fervour, Greatbear remains embroiled with the old wave of cassettes.

Cassettes from the 1960s and early 1970s carry specific preservation concerns.

Loss of lubricant is a common problem. You will know if your tape is suffering lubricant loss if you hear a horrible squealing sound during play back. This is known as ‘stick slip,’ which describes the way friction between magnetic tape and tape heads stick and slip as they move antagonistically through the tape transport.

This squealing poses big problems because it can intrude into the signal path and become part of the digital transfer. Tapes displaying such problems therefore require careful re-lubrication to ensure the recording can be transferred in its optimum – and squeal free – state.

Early compact cassettes also have problems that characterise much ‘new media.’

As Eric D. Daniel et al elaborate: ‘during the compact cassette’s first few years, sound quality was mediocre, marred by background noise, wow and flutter, and a limited frequency range. While ideal for voice recording applications like dictation, the compact cassette was marginal for musical recording.’ [2]

The resurgence in compact cassette culture may lull people into a false sense that recordings stored on cassettes are not high risk and do not need to be transferred in the immediate future.

It is worth remembering, however, that although playback machines will continue to be produced in years to come, not all tape machines are of equal, archival quality.

The last professional grade audio cassette machines were produced in the late 1990s and even the best of this batch lag far behind the tape machine to end all tape machines – the Nakamichi Dragon with its Automatic Azimuth Correction technology – that was discontinued in 1993.

To ensure the best quality transfers it is advisable to play back tapes using professional-grade machines. This enables greater control of problems that can arise with azimuth, wow and flutter which often need to be checked and if necessary adjusted prior to playback, a process that is not possible on cheaper, domestic machines.

As ever, if you have any specific concerns or enquiries regarding your audio cassette collections, please contact us to discuss it.

Notes

[1] Eric D. Daniel et al, eds. (2009) Magnetic Recording: The First 100 Years. Piscataway: IEEE Press Marketing, 103-104.

[2] Eric D. Daniel et al, eds, Magnetic Recording, 104.