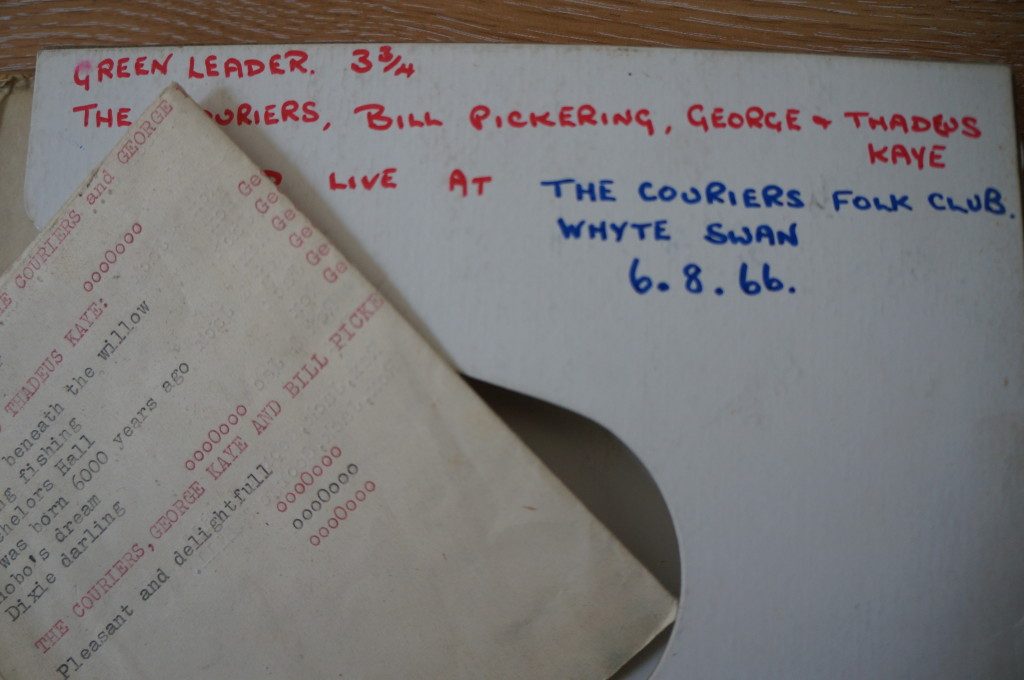

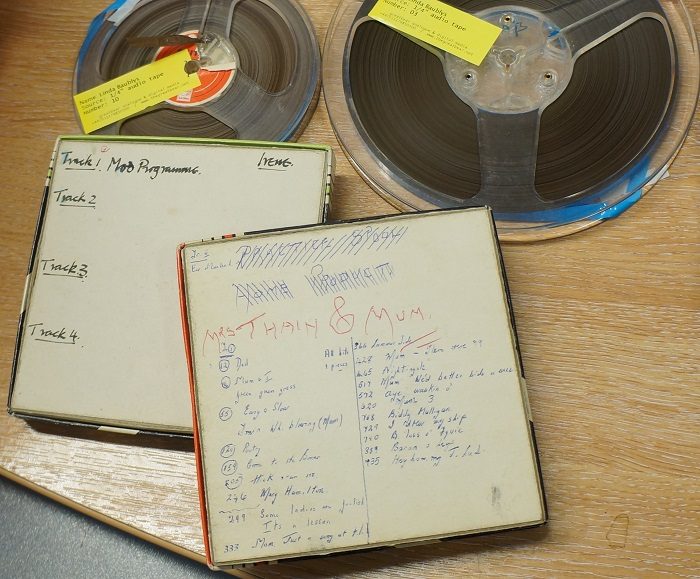

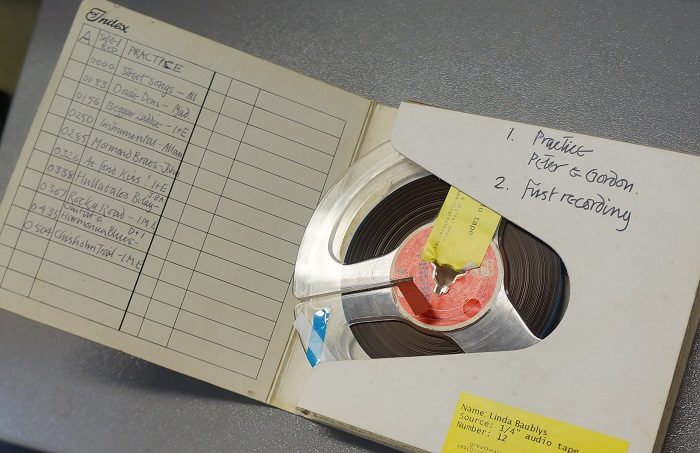

The tapes, that were sent by her niece Mrs. Linda Baublys, are documents of her Auntie’s passion, and include recordings Irene made of folk music sung in a mixture of Gaelic and English at the Gellions pub, Inverness, in the late 1960s.

The tapes also include recordings of her family singing together. Linda remembered fondly childhood visits to her ‘Granny’s house that was always filled with music,’ and how her Auntie used to ‘roar and sing.’

Perhaps most illustriously, the tapes include a prize-winning performance at the annual An Comunn Gaidhealach/ The National Mòd (now Royal National Mòd). The festival, which has taken place annually at different sites across Scotland since it was founded in 1892 is modelled on the Welsh Eisteddfod and acts ‘as a vehicle for the preservation and development of the Gaelic language. It actively encourages the teaching, learning and use of the Gaelic language and the study and cultivation of Gaelic literature, history, music and art.’ Mòd festivals also help to keep Gaelic culture alive among diasporic Scottish communities, as demonstrated by the US Mòd that has taken place annually since 2008.

If you want to find out more about Gaelic music visit the Year of the Song website run by BBC Alba where you can access a selection of songs from the BBC’s Gaelic archive. If you prefer doing research in archives and libraries take a visit to the School of Scottish Studies Archives. Based at the University of Edinburgh, the collection comprises a significant sound archive containing thousands of recordings of songs, instrumental music, tales, verse, customs, beliefs, place-names biographical information and local history, encompassing a range of dialects and accents in Gaelic, Scots and English.

As well as learning some of the songs recorded on the tape to play herself, Linda plans to eventually deposit the digitised transfers with the School of Scottish Studies Archives. She will also pass the recordings on to a local school that has a strong engagement with traditional Gaelic music.

Digitising and country lanes

Linda told us it was a ‘long slog’ to get the tapes. After Irene died at the age of 42 it was too upsetting for her mother, and Linda’s Granny, to listen to them. The tapes were then passed onto Linda’s mother who also never played the tapes, so when she passed away Linda, who had been asking for the tapes for nearly 20 years, took responsibility to get them digitised.

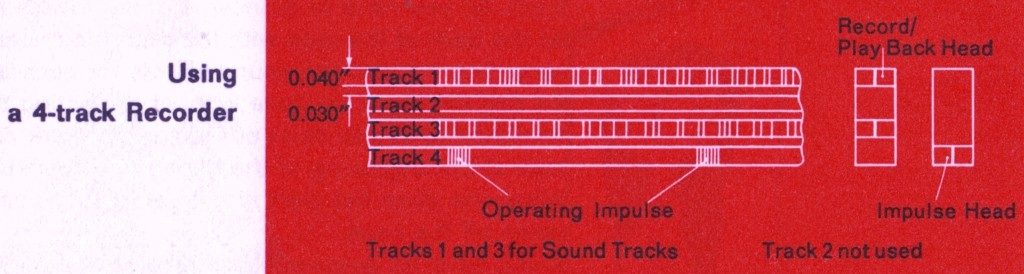

The tapes were in fairly good condition and minimal problems arose in the transfer process. One of the tapes was however suffering from ‘country-laning’. This is when the shape of the tape has become bendy (like a country lane), most probably because it had been stored in fluctuating temperatures which cause the tape to shrink and grow. It is more common in acetate-backed tape, although Linda’s tapes were polymer-backed. Playing a tape suffering from country-laning often results in problems with the azimuth because the angle between tape head and tape are dis-aligned. A signal can still be discerned, because analogue recordings rarely drop out entirely (unlike digital tape), but the recording may waver or otherwise be less audible. When the tape has been deformed in this way it is very difficult to totally reverse the process. Consequently there has to be some compromise in the quality of the transfer.

We hope you will enjoy this excerpt from the tapes, which Linda has kindly given us permission to include in this article.