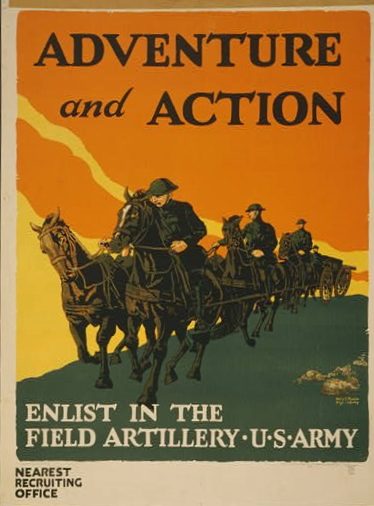

Across the world, 2014-2018 will be remembered for its commitment to remembrance. The events being remembered are, of course, those related to the First World War.

The UK government has committed over £50 million pounds for commemoration events such as school trips to battlefields, new exhibitions and public ceremonies. If you think that seems like a little bit too much, take a visit to the No Glory in War website, the campaign group who are questioning the purposes of commemorating a war that caused so much devastation.

The concerns raised by No Glory about political appropriation are understandable, particularly if we take into account a recent Daily Mail article written by current Education Secretary Michael Gove. In it Gove stresses that it is

‘important that we commemorate, and learn from, that conflict in the right way in the next four years. […] The war was, of course, an unspeakable tragedy, which robbed this nation of our bravest and best. Our understanding of the war has been overlaid by misunderstandings, and misrepresentations which reflect an, at best, ambiguous attitude to this country and, at worst, an unhappy compulsion on the part of some to denigrate virtues such as patriotism, honour and courage.

The conflict has, for many, been seen through the fictional prism of dramas such as Oh! What a Lovely War, The Monocled Mutineer and Blackadder, as a misbegotten shambles – a series of catastrophic mistakes perpetrated by an out-of-touch elite. Even to this day there are Left-wing academics all too happy to feed those myths.’

Gove clearly understands the political consequences of public remembrance. In his view, popular cultural understanding of the First World War have distorted our knowledge and proper values ‘as a nation’. There is however a ‘right way to remember,’ and this must convey particular images and ideas of the conflict, and Britain’s role within it.

Digitisation and re-interpretation

While the remembrance of the First World War will undoubtedly become, if it has not already, a political struggle over social values, digital archives will play a key role ensuring the debates that take place are complex and well-rounded. Significant archive collections will be digitised and disseminated to wide audiences because of the centenary, leading to re-interpretation and debate.

The BBC are facilitating discussions through features on their significant commemoration site, including an interesting consideration of the enduring influence of poet Wilfred Owen. Jisc and Oxford University have also collaborated to create an Open Educational Resource supporting new directions in teaching the First World War.

If you want a less UK-centric take on remembrance you can visit the Europeana 1914-1918 Website or Centenary News, a not-for-profit organisation that has been set up to provide independent, impartial and international coverage of the Centenary of the First World War.

Other, less ‘curated’ resources, abound online. For example, the Daily Telegraph has digitised every newspaper published between 1914-1918, with each edition being ‘published’ on its centenary date. The British Library’s excellent timeline series include one relating to the First World War. Significant parts of the National Archives’ First World War collections are available to access online, including copies of war diaries, Victoria Cross and service registers for members of the Army, Navy, Airforce and War Nurses. You can also listen to ‘Voices of the Armistice,’ a series of recordings relating to Armistice Day. Similar to the Soldier’s Stories Audio Gallery on the BBC, these recordings are not the oral testimony of soldiers, but actors reading excerpts from their diaries or letters.

Oral Testimonies of the First World War

Large amounts of digitised material about the First World War are paper documents, given that portable recording technologies were not in wide scale use during the years of the conflict.

The first hand oral testimonies of First World War soldiers have usually been recorded several years after the event. What can such oral records tell us that other forms of archival evidence can’t?

Since it became popular in the 1960s and 1970s, oral histories have often been treated with suspicion by some professional historians who have questioned their status as ‘hard evidence’. The Oral History Society website describe however the unique value of oral histories: ‘Everyone forgets things as time goes by and we all remember things in different ways. All memories are a mixture of facts and opinions, and both are important. The way in which people make sense of their lives is valuable historical evidence in itself.’

We were recently sent some oral recordings of Frank Brash, a soldier who had served in the First World War. The tapes, that were recorded in 1975 by Frank’s son Robert, were sent in by his Great-Grandson Andrew who explained how they were made ‘as part of family history, so we could pass them down the generations.’ He goes on to say that ‘Frank died in 1980 at the age of 93, my father died in 2007. Most of the tapes are his recollections of the First World War. He served as a machine gunner in the battles of Messines and Paschendale amongst others. He survived despite a life expectancy for machine gunners of 6 days. He won the Military Medal but we never found out why.’

Excerpt used with kind permission

If you are curious to access the whole interview a transcript has been sent to the Imperial War Museum who also have a significant collection of sound recordings relating to conflicts since 1914.

The recordings themselves included a lot of tape hiss because they were recorded at a low sound level, and were second generation copies of the tapes (so copies of copies).

Our job was to digitise the tapes but reduce the noise so the voices could be heard better. This was a straightforward process because even though they were copies, the tapes were in good condition. The hiss however was often as loud as the voice and required a lot of work post-migration. Fortunately, because the recording was of a male voice, it was possible to reduce the higher frequency noise significantly without affecting the audibility of Frank speaking.

Remembering the interruption

‘Never has experience been contradicted more thoroughly than the strategic experience by tactical warfare, economic experience by inflation, bodily experience by mechanical warfare, moral experience by those in power. A generation that had gone to school on a horse drawn street-car now stood under the empty sky in a countryside in which nothing remained unchanged but the clouds, and beneath these clouds, in a field of force of torrents and explosions, was the tiny, fragile human body.’

Of course, it cannot be assumed that prior to the Great War all was fine, dandy and uncomplicated in the world. This would be a romantic and false portrayal. But the mechanical force of the Great War, and the way it delayed efforts to speak and remember in the immediate aftermath, also needs to be integrated into contemporary processes of remembrance. How will it be possible to do justice to the memory of the people who took part otherwise?