We are living in interesting times for digital video preservation (we are living in interesting times for other reasons too, of course).

For many years digital video preservation has been a confusing area of audiovisual archiving. To date there is no settled standard that organisations, institutions and individuals can unilaterally adopt. As Peter Bubestinger-Steindl argues, ‘no matter whom you ask [about which format to use] you will get different answers. The answers might be correct, but they might not be the right solution for your use-cases.’

While it remains the case that there is still no one-size-fits-all solution for digital video preservation, recent progress made by the Codec Encoding for LossLess Archiving and Realtime transmission (CELLAR) working group should be on the radar of archivists in the field.

The aim of CELLAR is to standardise three lossless open-source audiovisual formats – Matroska, FFV1 and FLAC – for use in archival environments and transmission.

To date the evolution of video formats has largely been driven by broadcast, production and consumer markets. The development of video formats for long term archival use has been a secondary consideration.

The work on the Matroska container, FFV1 video codec and FLAC audio codec is therefore hugely significant because they have, essentially, been developed by audiovisual archivists for audiovisual archivists.

Other key points to note is that Matroska, FFV1 and FLAC are:

1. Open Source. This increases their resilience as a preservation format because the code’s development is widely documented.

And, importantly, they employ

2. Lossless compression. Simply put, lossless compression makes digital video files easier to store and transmit: file size is decreased without damaging integrity.

Managing large file sizes has been a major practical glitch that has held back digital video preservation in the past. The development of effective lossless compression for digital video is therefore a huge advance.

Archival focus

The archival-focus is evident in the capacities of Matroska container, as outlined by Dave Rice and Ashley Blewer in a paper presented at the ipres conference in 2016.

Here they explain that ‘the Matroska wrapper is organized into top-level sectional elements for the storage of attachments, chapter information, metadata and tags, indexes, track descriptions, and encoding audiovisual data.’

Each of these elements has a checksum associated with it, which means that each part of the file can be checked at a granular level. If there is an error in the track description, for example, this can be specifically dealt with. Matroska enables digital video preservation to become targeted and focused, a very useful thing given the complexity of video files.

It is also possible to embed technical and descriptive metadata within the Matroska container, rather than alongside it in a sidecar document.

This will no doubt make Matroska attractive to archivists who dream of a container-format that can store additional technical and contextual information.

Yet as Peter B. Hermann Lewetz and Marion Jaks argue, ‘keeping everything in one video-file increases the required complexity of the container, the video-codec – or both. It might look “simpler” to have just one file, but the choice of tools available to handle the embedded data is, by design, greatly reduced. In practice this means it can be harder (or even impossible) to view or edit the embedded data. Especially, if the programs used to create the file were rare or proprietary.’

While it would seem that embedding metadata in the container file is currently not wholly practical, developing tools and systems that can handle such information must surely be a priority as we think about the long term preservation of video files.

FFV1 and FLAC are also designed with archival use in mind. FFV1, Rice and Blewer explain, uses lossless compression and contains ‘self-description, fixity, and error resilience mechanisms.’ ‘FLAC is a lossless audio codec that features embedded checksums per audio frame and can store embedded metadata in the source WAVE file.’

Milestones for Digital Video Preservation

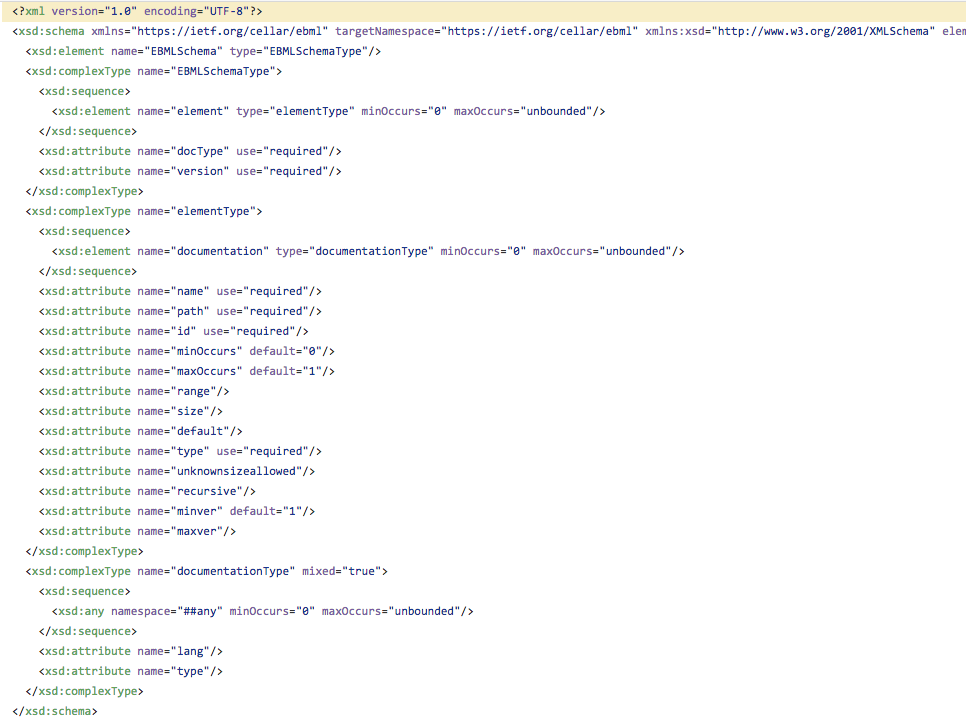

By the end of 2016 the CELLAR working group will have submitted standard and information specifications to the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG) for Matroska, FFV1, FLAC and EBML, the binary XML format the Matroska container is based on.

Outside of CELLAR’s activities there are further encouraging signs of adoption among the audio visual preservation community.

The Presto Centre’s AV Digitisation and Digital Preservation TechWatch Report #04 has highlighted the growing influence of open source, even within commercial audio visual archiving products.

Austrian-based media archive management company NOA, for example, ‘chose to provide FFV1 as a native option for encoding within its FrameLector products, as they see it has many benefits as a lossless, open source file format that is easy to use, has low computational overheads and is growing in adoption.’

We’ll be keeping an eye on how the standardisation of Matroska, FFV1 and FLAC unfolds in 2017. We will also share our experiences with the format, including whether there is increased demand and uptake among our customer base.

Regarding “The work on the Matroska container, FFV1 video codec and FLAC audio codec is therefore hugely significant because they have, essentially, been developed by audiovisual archivists for audiovisual archivists”: while audiovisual archivists have been involved in some form or another in part of the development of these formats (as authors, sponsors, instigators) the foundational work on these formats was not done by audiovisual archivists. Lots of credit to Steve Lhomme and Moritz Bunkus for developing Matroska and Michael Niedermayer and FFmpeg developers for developing FFV1.

Dave Rice