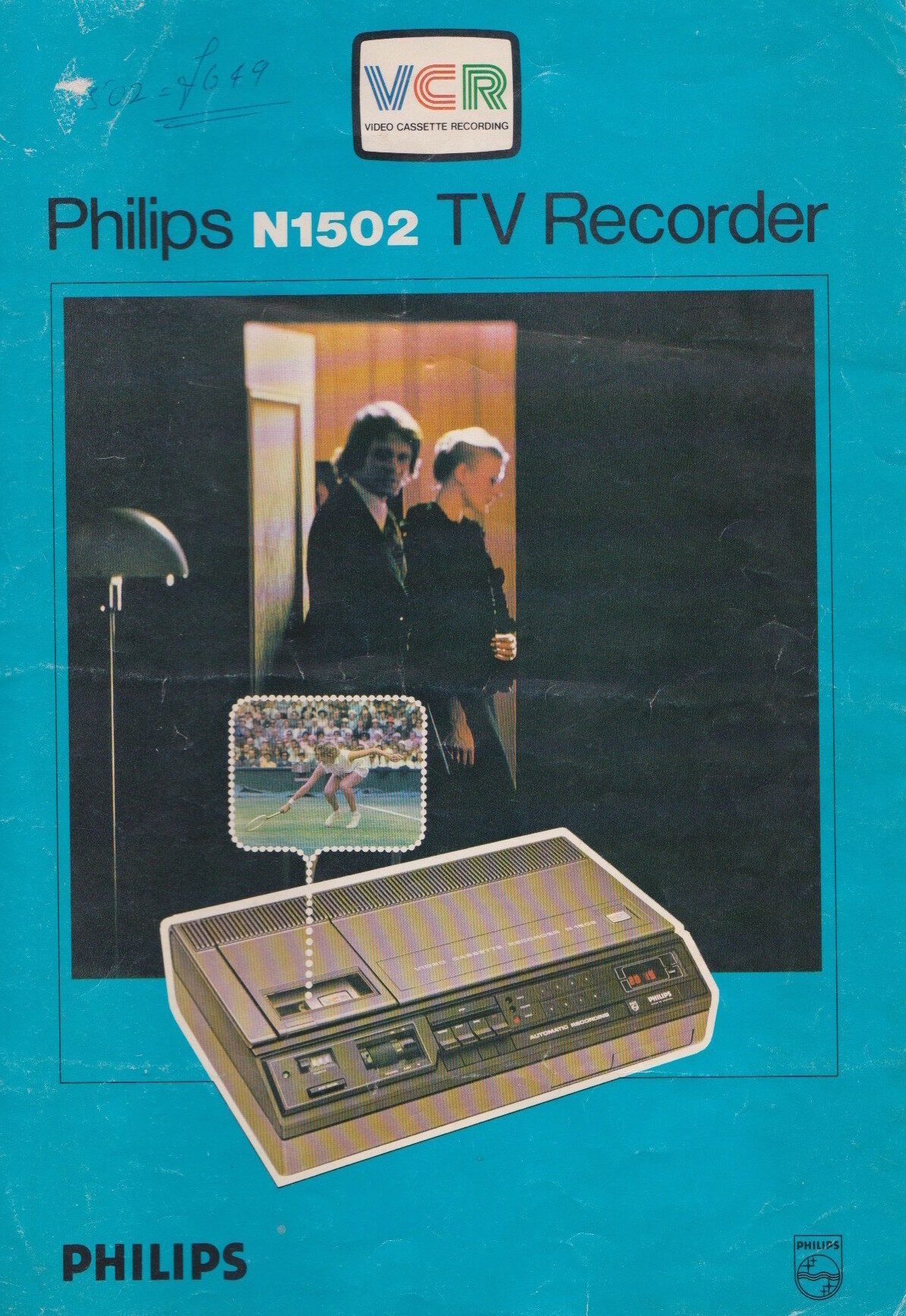

The front page of the Philips N-1502 TV Recorder catalogue presents a man peering mournfully into a dark living room. A woman, most probably his wife, drags him reluctantly out for the evening. She wants to be social, distracted in human company. The N-1502 tape machine is superimposed on this unfamiliar scene, an image of… Continue reading Philips N-1502 TV Recorder